It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. This past Easter Sunday, I had the chance to visit two exhibitions at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, both of which I’d been looking forward to with great anticipation. Between the blockbuster Frida Kahlo show, and another featuring the photography of Lee Miller—both of whom celebrated centenaries in 2007—I was expecting an embarrassment of riches. In retrospect, it was an at times frustrating, at times downright disappointing, experience—but one that I would recommend to anyone interested in the work of these women anyway. (The Miller show will have just closed as this issue comes out; the Kahlo show continues through May 18. Both will then go on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art this summer.)

As well known as Kahlo is today—especially since the striking bio-pic starring Salma Hayek in 2002—it’s still a rare thing to actually see much of her work. As a result, the prospect of seeing some 42 of her paintings seemed like it would be a real treat.

Unfortunately, as is often the case with these vigorously advertised blockbusters—it’s difficult to go anywhere in Philadelphia without encountering the world’s most famous unibrow—and despite a timed ticket system, the sheer mass of humanity within the walls of the exhibition made locating oxygen a challenge, let alone spending any time really looking at the work. (In the end, I concluded that the timed ticket scheme amounted to stamping the date and time the visitor arrived on the ticket, not actually regulating the number of people allowed in at any one time.)

It’s always an interesting exercise to encounter in person works that you’ve only seen in reproduction previously. For example, I was shocked to discover how large the famous Two Fridas painting was, each of the seated women approaching something like life size, even as most of her work was done on a much more intimate scale. I was struck by the intensity and power of some of her late still life paintings, which were done mostly as her health deteriorated near the end of her life. That these are less immediately popular—despite the strength of the works themselves—is testimony to the addictive power of celebrity, the primacy of personal charisma that draws the crowds to this exhibition to see their beloved “Frida.”

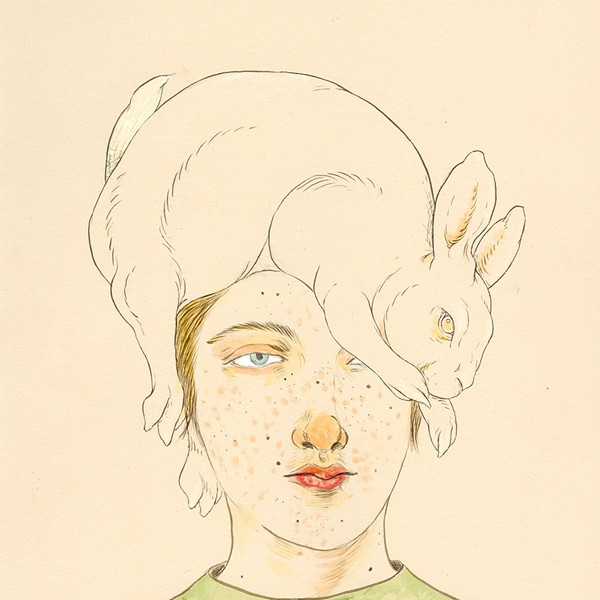

Kahlo is herself partly culpable in this cult of personality. It has much to do with the alluring myth that she helped to spin about herself, folding in the traumatic injuries she received while still a teenager in a terrible street car accident in Mexico City. (Impaled by a metal bar that exited via her vagina, Kahlo was to suffer almost constant pain, a series of more than 50 operations, and the inability to carry a pregnancy as a result.) Many of her paintings vividly portray the strong feelings and frustrations of her life, the infidelities of her husband, muralist Diego Rivera (who had an affair with Frida’s sister, among others), the miscarriages, and the richness of indigenous Mexican culture, always close to her heart.

The fact of the matter is that Frida herself played an active role in constructing her mythic persona, with a persistence that rivaled her dedication to the painting itself. “Frida” was perhaps her greatest creation, a performance piece that was first resurrected in Hayden Herrera’s 1983 biography (which reported all the flamboyant details of this persona, without however finding much critical distance from it). The rest is now history, as they say—the 1980s marked the birth of a new Frida industry, as Madonna emerged as a serious collector of her work, and her star went supernova. Not too surprisingly, the final gallery of the exhibition lets the crowd of visitors directly into a large, well-stocked gift shop, the walls painted deep blue just like her famous house (now a museum) in Mexico City.

Heading downstairs, I was confronted with an entirely reversed phenomenon. Tucked away in a set of subterranean galleries, “The Art of Lee Miller” was almost deserted. A series of immaculately framed photographs lined the dark grey walls, the exhibition was the very embodiment of museological restraint—in sharp relief to the wildness that characterized Miller’s life.

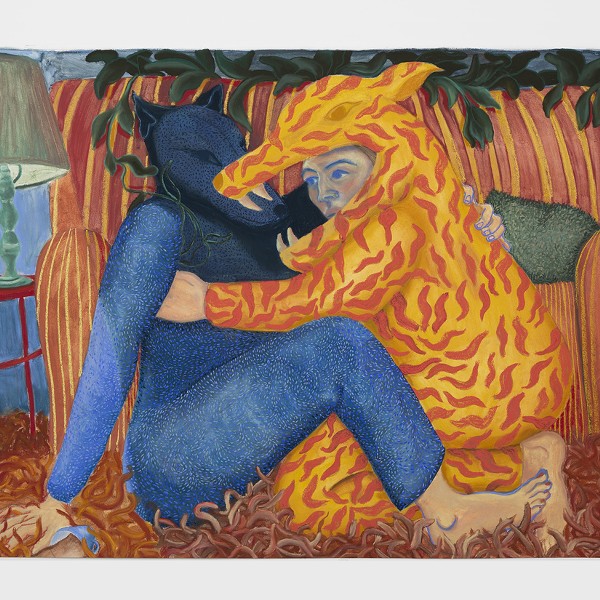

Born and raised in Poughkeepsie (which I guess helps make this something of a local story for us), Miller, like Kahlo, led a pretty spectacular life. Accidentally falling into an early career as a model for Vogue—she was a striking, blond beauty—she eventually went to Paris, where she served as a studio assistant, model, and lover to Man Ray, in the heart of the Surrealist circle. Not one to let moss grow under her feet, a few years later she left Man to start her own studio in New York; two years later, she impetuously married an Egyptian businessman who’d fallen for her in Paris, moving to Cairo. Growing restless in that marriage, she reconnected with her Surrealist friends in Paris, meeting English painter Roland Penrose, eventually moving in with him in London. By that time, World War II was starting, and she eventually crafted a unique assignment for herself as the war correspondent photographer for, of all things, Vogue magazine. From the Blitz in London to zones of active combat after D-Day, through the liberation of Paris and on to the camps at Buchenwald and Dachau, she created a unique body of war work, shaped by a Surrealist sensibility possessed by no other photographer of the conflict.

All this is dutifully periodized and catalogued in the show, which features 140 pictures selected by esteemed photography curator Mark Haworth-Booth. Despite the inclusion of two notorious photographs from her early Paris period—Miller asked a doctor friend to rescue the amputated breast of a mastectomy patient, which she photographed laid out on a plate, complete with table setting, a macabre Surrealist provocation seen here publicly for the first time—as an exhibition, it falls a bit flat.

While she was an excellent printer of her own work, having honed her darkroom chops working for Man Ray, the emphasis on vintage prints in the show skews many images toward smaller sizes, even contact prints in some cases. And the World War II work, which arguably represents her greatest achievement, is then given fairly short shrift, as she wasn’t printing her own negatives much then, but sending her films back to the London Vogue office to be produced for the magazine. And while there is a small case in the galleries presenting several issues of the magazine, the importance of the published context for her photographs (and the extensive writing she did to accompany them) is largely lost.

The excellent catalogue by Haworth-Booth should stand for some time as a benchmark summary of Miller’s career; unfortunately, the conservative strategy pursued in hanging the show (emphasizing the rare vintage prints, and the overly spare wall text, which did not explain the specific context of any of the images, despite what was obviously a very sensitive and informed selection of what to exhibit) ultimately failed to deliver on the promise of the scholarship of the catalogue.

These shows of these two women—one endlessly self-mythologizing, the other restlessly rebellious—illustrate opposite poles of the curatorial art. For Kahlo, it’s the pack-em-in ethos of the blockbuster exhibition (and all the better to set the gift shop registers ringing), while Miller’s work is left to languish in an overly dry, somewhat academic presentation. It makes me wonder—can’t there be some happy meeting point somewhere in the middle?