Upon visiting Rachel Harrison’s current exhibition “Consider the Lobster and Other Essays” at the Hessel Museum at Bard College, those familiar with the funky, polychromed-steel sculptures by German artist Franz West installed outside the entrance will notice something different about them. Harrison has adorned the two polyp-shaped protuberances on one of West’s biomorphic sculptures with wigs, thereby appropriating the work of another artist (a familiar strategy of Harrison’s) and anthropomorphizing the shapes so that we read them as heads. Look up and see what’s flying at the top of the flagpole—she has replaced Old Glory with a new and improved American flag; a stylized eagle patriotic enough for Stephen Colbert. For Harrison, the world of objects—including objects made by other artists—represents an infinite resource of materials to be transformed through context and juxtaposition into her art.

Don’t bother trying to figure out what Harrison’s work means. You may notice yourself attempting to do this. But like any good trip, the journey is the destination. Being aware of your own desire to make meaning out of chaos and apparent randomness is the meaning of her work, or, at least, one of them. Her 1997 installation Snake in the Grass is a case in point. It’s a mixed-media installation that includes photographs, wall panels belayed from the ceiling and anchored to the floor via ropes, green plastic bags filled with who-knows-what, brightly painted, cut-out abstract shapes, found objects, and a snake skin. (Harrison’s work is almost impossible to describe because there’s so much visual information.) If you spend enough time deciphering the signs and are familiar with some of the images, you may deduce that the piece has something to do with the Kennedy assassination (I had the benefit of a well-informed member of the staff to clue me in). But that’s as far as you go—the work isn’t about that; there is no commentary. Harrison uses the event as a touchstone, an anchor—subject matter for her is simply one more readymade to be appropriated.

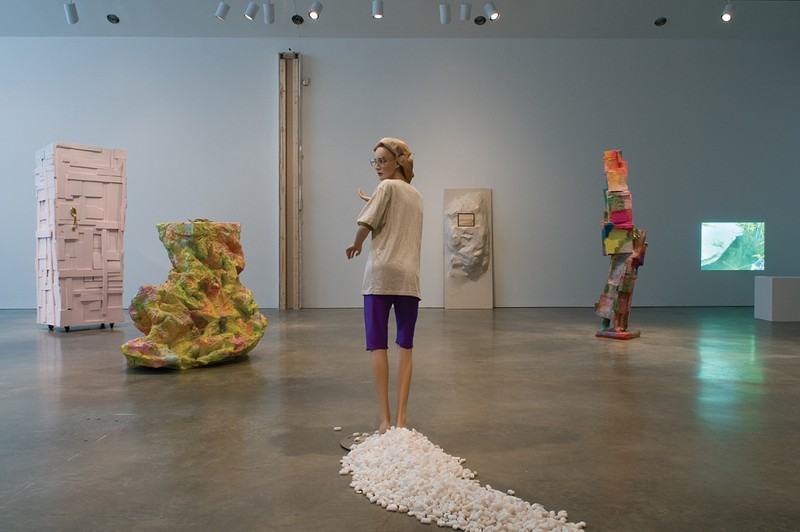

One of the things that keeps the potential for total visual chaos and inconsistency at bay are her sculptural “surrogates.” These are objects that she makes using extruded foam insulation board that she cuts up and builds into abstract mounds, sometimes monolithic, which are then slathered with textured paste and painted with her signature lurid, iridescent acrylic color, which evokes the painting of such modernist masters as Jules Olitski and Helen Frankenthaler. These works refer to the history of sculpture as “statue” but remain, like all of her work, contingent upon their relationship to other objects and to the gallery context, none of which is ever simply given. Her work is like a postmodern car that runs on modernist fuel.

Ultimately, Harrison’s work succeeds because it works visually. She is an installation artist, which in her case means that the work incorporates the conventions of painting, sculpture, architecture, photography, video, and performance. She’s a masterful colorist with a canny sense of scale and proportion.

I asked her about a 2007 piece entitled Foot Stays in the Picture, which she referred to as “the Donald Judd piece,” evoking as it does the repeated boxes of the high priest of minimalism. I wondered if the video of feet running in the New York City Marathon, which is visible through cutout shapes in the pedestal-like boxes subtly plied with color, was shot with the creation of this particular piece in mind. “I never know what I’m doing,” replied Harrison. Let’s hope it stays that way.

“Consider the Lobster and Other Essays,” will be exhibited at the Hessel Museum at Bard College through December 20. (845) 758-7598; www.bard.edu/ccs.