Meredith opened her eyes, rolled onto her side, and stared out the window of her mother’s Winnebago. Trees whizzed by, followed by the peaks of unfamiliar homes, and telephone poles carrying messages from friends, friends who knew each other well, since third grade, and who shared secrets and boyfriends, gossip and makeup, reliving the lives of their mothers and grandmothers in the same town, the same village, the same county as all of their ancestors. Permanent residents, lucky to be living in such stability.

“Wake up, sleepyhead, rise and shine!”

“I’m up, Mother.”

“The early bird catches the worm.”

“I no longer eat worms for breakfast, Mother.”

“It’s easier to catch a fly with sugar than with vinegar.”

Meredith cringed at the constant barrage of platitudes flung from the front seat by the always cheerful Kathleen Lynda Sullivan. Stretching, she placed her feet on the rocking floor and balanced herself as she made her way into the phone booth of a bathroom she and her mother had been sharing for several days. A quick shower refreshed her, enabling her to take over driving duties while her mother lay down for a short nap.

“I only need 20 minutes, and I’ll be good as new.”

Meredith knew her mother’s fictitious 20 minutes lasted hours, but she did not challenge her optimism. No one challenged Kathleen’s optimism. They just left her in her delusional world as she made her way from town to town looking for work, for a home, for a life worth living.

“Bloom where you are planted,” she would say whenever they hit a new town. Within months, they were uprooting, disconnecting, killing the shoots of hope for a reasonable and stable existence for which Meredith longed.

She turned on the wipers as a light rain began to fall. She checked the rearview mirror. “God Helps Those Who Help Themselves” hung from its arm. She glanced in the mirror at the junk her mother lovingly called her inheritance. It was difficult to miss the distractions of posters, placards, and signs plastered on every available space. “God Doesn’t Make Junk,” proclaimed one poster. “Yeah,” thought Meredith, “then where the hell did all this shit come from?” “Today is the First Day of the Rest of Your Life.” She cringed, wondering whatever happened to the first part of her life. “Children Learn What They Live.” Her favorite. She’s learned that people who run away from their lives can spend a lifetime on the road, and she, for one was tired of running. Watching the flat, desolate landscape whiz by, she thought that even this most inhospitable place was preferable to nowhere. But they were going somewhere. Alabama. Mobile. A job with a second cousin who owned a munitions plant. Secretarial, they both qualified; only one could use a computer, but the other would learn. “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.”

Eighteen hours later they arrived at their destination, a small apartment complex two miles from the plant. Meredith climbed down from the motor home, looked around and smiled. A swimming pool glistened in the middle of the complex, and behind it a lush garden filled with magnificent flowers and shrubs. That is what she missed the most. Her garden. When she was little, her father had taught her how to grow beautiful vegetables. He also taught her the secrets of pruning and fertilizing, planting and grafting, and she knew just about every flowering tree and shrub in the southern half of the United States. While her mother filled out paperwork, Meredith toured the grounds. “Someone here loves dirt as much as I do,” she thought.

She bent down to smell the sweet earth, lifting a large clump in her hands.

“Better not eat that stuff,” drawled a deep voice. “It ain’t supper time yet.”

Standing behind her was a slender man, about 22, in a T-shirt and blue jeans, with a bandanna tied around his head. His long brown hair hung behind his ears in a ponytail, and he had a tattoo of a rose on his arm.

“Oh-h, I . . .I’m sorry,” she stammered.

“I hope I didn’t frighten you none.”

“No, no, I just was admiring your garden.”

“T’aint mine. I’m the gardener. Mr. Frank, the owner, he says that a garden and landscaping increases the value of property. He owns a lot of property in Mobile, and I make sure all of it looks like an English tea garden.”

Meredith smiled at the thought of this young handsome man’s knowledge of English tea gardens.

“I’m here every Tuesday and Friday, watering, weeding, pruning. Sometimes I stop by on Sundays, too, to check on my gardenias. They are very delicate. I don’t mind working weekends, not much else to do in Mobile but work.”

“My mother and I will be working in the office of Moran Munitions.”

“Oh, I know Mr. Moran. Nice wife. I think her name is Maureen. Can’t say much for him. Doesn’t have a blade of grass on his property. Poured concrete over everything. ‘Too much to keep up,’—I’m quoting now—‘working 80 hours a week.’ Anybody working 80 hours a week is crazy, and anybody pouring concrete over perfectly good grass is really crazy, don’t you agree?”

“I hope not. He’s not only my boss, he’s my mother’s second cousin. I pray it’s not hereditary, even though it would explain a lot,” she chuckled.

He chuckled back. “Well, nice meeting you.”

She hesitated: “Umm, could I ask a favor? I’m a bit of a gardener myself. Could I borrow a few tools on the weekend? I’d love to plant some vegetables, just enough for Mother and myself. Shouldn’t take up much room. Maybe 12x12?”

“Sure, help yourself. I leave everything here on Friday evenings in the shed. The door is always open. Not much to steal.”

“Thank you so much. You don’t know what this means to me. A patch of ground to call my own. By the way, my name is Meredith Sullivan.”

“Nice t’meet you. I’m Andrew Nuttall. Round here everybody calls me Dewey.”

“Which do you prefer?”

“Well, actually, nobody ever asked me that before, but I truly do prefer Andrew.”

“Well, Andrew, I thank you again. I’ll start tomorrow.”

Saturday was hot, humid, and oppressive to the regular citizens of the county. Meredith was up before the humidity took a nasty turn from oppressive to crippling, and began digging her garden. She pushed her weight against the spade to turn the earth, then hoed and raked to loosen and prepare the soil. She fertilized it, then staked and strung the rows. When the temperature hit 95 degrees, she went inside, showered, then took a ride into town. She found a seed store, bought packets of carrots, broccoli, squash, cherry tomatoes, peppers, and lettuce. She also bought several packs of marigolds to surround her garden as bug repellent. The lettuce should have been planted weeks ago, but she didn’t care. She wanted to reproduce the garden of her childhood, all of her favorite vegetables picked ripe, eaten sweet and tender. This would be a summer to bless.

“Bless This Mess” was being hammered over the kitchen window. “About time you came in, girl. You will die in this heat.”

“I’ll plant the seeds after sundown, Mother. Found a store in a real nice commercial section. Looks like a couple nice restaurants, a shoe store, hardware store, library. Let’s go out to dinner so I can show you.”

“Is there a church nearby?”

“Yes, Mother, I think it’s a Methodist.”

“Methodist? Where’s the Baptist?”

“Didn’t see one, but I’m sure there’s one somewhere close by.”

“Sure hope so. ‘Nearer, my God, to Thee’” reverberated, shrill and past her range, throughout the kitchen.

“What about the restaurant?”

“Waste not, want not, child.” We’d better get that first paycheck before we treat ourselves to dinner. Wash up, now. Cleanliness is next to Godliness.”

Meredith gritted her teeth as she wound through the apartment, trying to remember where the bathroom door was. Bowing down to the yellowed sink, she washed her hands and prayed to the only god she trusted. “Daddy, if you have any clout up there in heaven, please call her home. I’m so tired of trying.” Fatigue and regret sat heavily on her five-foot frame, causing tears to flow. “Give me strength, oh Lord, give me strength.” She remained in her penitential bow for several minutes while the salty pearls ran across her hands.

They started the job on Monday. Mundane, trivial work, but two paychecks would cover the rent and essentials. Andrew was right. Mr. Moran—Jimmy, her mother called him—was a bit of a tyrant to the rest of the employees but had a soft spot in his heart for his cousin. The day dragged until five o’clock, they were home by five fifteen, supper by six, and gardening until so late she couldn’t see.

Her vegetables needed little tending other than watering, so she spent time with the beautiful roses, azaleas, and magnolias. She sprayed for pests and watered on the days Andrew was not there. On Tuesdays and Fridays, he hung around past his work time so they could talk, mostly about the garden, but eventually about other things that young men and women find compelling. Their garden visits evolved into an occasional walk for an ice cream cone, and a few weeks later, suppers at the Cozy Cotton Diner.

“Dating a man you hardly know. What’s wrong with you, child? I remember what my mama told me before I married your daddy: ‘Look before you leap,’ she warned. Wish I had heeded her advice.”

The slur angered Meredith further, but she controlled her voice.

“He’s the only friend I have in this town, Mother.”

“What about our coworkers?”

“There’s no one my age. Some of them have one leg in the grave.”

“Meredith Frances Sullivan! They are all sweet, lovely ladies. They’ve taken quite a liking to you, but you hardly say a word.”

“I’m not in the mood, Mother. I have to get ready. Andrew and I are going to the movies.”

“On a work night! What’s gotten into you?”

“We’ll be home by nine thirty. I promise.”

She regretted that promise. The movie sparked a lively but friendly debate about the Civil War, and their walk from the theater took much longer than expected. As they approached her apartment, she sat on a stone wall to tie her sneaker. He sat beside her, put his arm around her, and gently nudged her ear. “I think I’m falling for the prettiest rose in my garden,” he whispered.

Meredith looked into his eyes, and saw not the color or the shape but the affection emanating from them. She didn’t know how to respond. She had never been this close to a man in her life. Nineteen, never been kissed, never in one spot long enough to be kissed. Once, in sixth grade, a boy named Tommy Sibbald kissed her on the cheek in the schoolyard after recess, but they moved from Arkansas that summer.

“Bloom where you are planted,” so she had wiped out the memory of that first innocent peck.

“Bloom where you are planted,” after they relocated to North Carolina, hundreds of miles from Danny Pierce and his flirting eyes.

“Bloom where you are planted,” after their trek to the Panhandle of Florida and her overwhelming crush on a blond classmate, whose name she never knew.

Five months here, eight months there, never long enough for a man this sweet or gentle to approach her and nudge her for a kiss. Her eyes sparkled in anticipation. He just smiled down at her beaming face.

“Well, aren’t you going to kiss me, Andrew Nuttall?”

“I was kinda hoping you would kiss me. You look like a very decisive woman.”

Her hands gently reached up to his neck, just like the redheaded actress in the movies that very night, and directed him to her lips. Standing in the breeze, they shared their first of many delightful kisses.

It was eleven before she walked into the darkened apartment.

“Thou shalt not fornicate, saith the Lord!”

“Mother, you frightened me to death.”

She turned just in time to avoid the flyswatter, the only available weapon in their sparsely equipped apartment.

“Love the sinner, hate the sin.” Swat, swat. “Repent, for you know not the day nor the hour.” Swat, swat. “Spare the rod and spoil the child.” Swat, swat.

“He who is without sin, cast the first stone,” Meredith retorted.

Her mother, stung by her own device, was speechless. Unable to formulate an original thought, she sat down. It took several minutes for her next barrage. “Meredith, you are so young. Don’t let this dirty, uncouth man win your heart. Love you and leave you, that’s what he’ll do!”

“Mother, he’s not dirty or uncouth. He is kind and hardworking. I am very, very fond of him. Please let me have this one thing, this one friend to call my own.”

“Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.”

“Yes, Mother, I know, I know.” What she knew was that her mother would never relent, never release her from this tiresome bondage.

For the next few months Meredith’s life took on a sense of order. Her vegetables grew in rich soil, were harvested and consumed with much pleasure. She often brought them to Andrew’s cabin and together they fixed dinner. He would barbecue while she sautéed vegetables and made a salad. There were always fresh flowers on his homemade table, mostly roses, but sometimes wild flowers he picked by the stream that bubbled on the edge of his property.

“My great-granddaddy built this cabin,” he related one evening. “The family almost forgot about it until about 10 years ago, when my uncle stumbled on it while hunting. My cousin John and I fixed it up real nice, put in electricity and plumbing—took us three years. Then John moved to D.C. and my daddy and uncle told me it was mine as long as I wanted it. I’ve been living in it ever since.”

“The only thing missing is a garden.”

“I just seem too busy tending Mr. Frank’s gardens to dig my own.”

“Let me do it, Andrew. Not much to do in my own with everything almost harvested. Please, I’d love to work the soil before winter. One last time to get my hands in the dirt.”

“Okay.” He smiled and kissed her lightly. “If I can’t keep my precious rose clean, might as well reap the benefits and eat the beans.”

She laughed at his ludicrous remark. That is what she loved more than anything about him. Original thought, appropriate sentences, direct communication, similes, alliteration, poetic license.

By November, she had turned the earth on a huge patch of backyard. He had to take down a willow and two maples so she would have enough sun. He also erected a fence to protect the garden from woodland creatures. She planted bulbs along the front so spring would be heralded by daffodils and tulips. She planned a patch for roses, a larger square for vegetables, and a corner for herbs. She drew an exact model so they would know how many rose bushes to buy in the spring, and where to plant the combined vegetables, those she loved and Andrew’s favorites: peas, string beans, and beets.

Just before Thanksgiving, Mr. Moran dropped a bomb in the munitions plant. He was closing the plant, moving it to Mexico where the labor was cheap. “Kathleen,” he proposed, “I am offering you and Meredith a raise to come with us. You have worked hard, learned quickly, and, well, being family and all, I trust you. I’ll pay for moving expenses, but you’ll have to be there by January first.”

Meredith’s hands froze above the keyboard. She could not react while her mother’s effusive response gave consent for both. Later that night, after a terrible argument that Meredith had no chance of winning, she sat in the barren garden and wept. She knew she didn’t have to go—she was 19. She also knew it was time to approach Andrew about their future, a future lost by January 1 if she did not speak now.

Andrew worked late the next day pruning the rose bushes. Meredith snuck up to him from behind, put her hands around his waist, and hugged him tightly. He turned and hugged her tighter still, lifting her a few inches off the ground. He snuggled his face in her neck and gave her a little nip on her ear.

“You smell like honeysuckle. Is that a new perfume?”

“I bought it special for tonight.”

“And why is tonight special?”

“I have a proposal for you.”

“And what proposal is that?”

“The proposal, Andrew. The only one that really matters.”

He pulled back slightly, looked her straight in the eyes, then smiled. “Well, you kissed me first, I guess you should do the proposing.”

“Will you?”

“Will I what?” he teased.

“Will you, Andrew Nuttall, marry me very soon, before January first?”

“Before January first? Why before January first?”

“Will you or won’t you?” She was half pouting, but very serious.

“Sweet pea, I’d marry you tonight if the State of Alabama would let me.”

“That’s all I needed to know. Thank you, my darling Andrew. I do love you so.” She danced up and down, elated, relieved, joyous.

She broke the news to her mother the next morning at breakfast. They never made it to work.

“Mother, please calm down, don’t you understand? I’m 19. I can make my own decisions. I’m not going to Mexico. I want a home, a permanent place to stay put, raise children, have friends. You can’t change my decision. We are being married next week. You can come if you want. We’re planning Saturday at the courthouse, if the judge is available.”

“You have to go to Mexico. I won’t know a soul there, don’t know the language, don’t know the money. Meredith, don’t desert me now, when I need you the most. Don’t you remember your Bible lessons? ‘Honor thy father and thy mother.’” She paused when Meredith crossed her arms in front of her chest, then glared at her disobedient daughter. In a flat monotone she sneered, “The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.”

Meredith most of all hated the double whammy. She despised two in a row, not only because they rarely flowed from one to another fluidly, making some sense, but also because she knew her mother’s thought process was no longer functioning.

“Bloom where you are planted, baby. You’ll see, we’ll be fine. You’ll meet somebody new, somebody better than that dirt digger who’s stealing your heart. It’s better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.”

Meredith, panicked at the thought of her precious Andrew lost, reached for the flyswatter. She was ready to swat her way out of the house and into the arms of her beloved husband-to-be. The flyswatter was not on its hook, so she grabbed the nearest thing, a cast iron skillet, and swung as hard as she dared. Kathleen Lynda Sullivan dropped to the floor, her skull dented slightly at the temple.

Stunned, Meredith stood over her mother’s body; she’s wasn’t sure for how long. Numb, feeling no remorse nor shame, she sat down pensively at the table and drank a cup of coffee. This could ruin her plans completely. Jail time instead of a honeymoon. She needed a foolproof plan of disposing the body, and could only think of one really safe place.

She called the office and told them that both she and her mother had come down with food poisoning. The rest of the day was spent packing Meredith’s things, disposing of her mother’s, and cleaning the apartment thoroughly. By midnight, everything was finished.

Dead weight is difficult to manage, especially for one as petite as Meredith. She solved the problem by using a sheet to slide the body down the steps and into the Winnebago. She slammed the heavy metal door, climbed into the driver’s seat, and ripped “God Helps Those Who Help Themselves” off the rearview mirror. She drove to Andrew’s house and parked on the road. Two hundred feet of driveway exhausted her, but there was no turning back. Meredith continued along the side of his house to the backyard and their garden. The soil, still loose, was easy to dig, and she had a shallow grave before two o’clock in the morning. She dumped her mother’s body in the grave, and stared down at her disheveled hair and dirty apron. Some rite would be appropriate, but what?

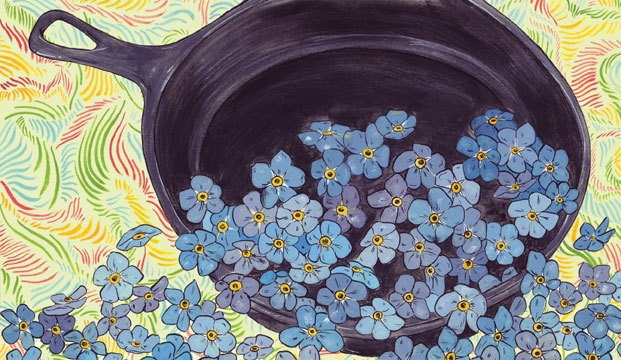

In the back of her mind this next part made sense, but it wasn’t until the summer that she really appreciated her actions. As she stood in the cold night air, she remembered a purchase earlier in the week. It was still in the car. Seeds for next year. Forget-me-nots on sale. She tiptoed quietly to the car, retrieved the slender packets, and opened them. Holding them above the grave, she sprinkled the seeds reverently over her mother, covering her from dented skull to platform shoes.

“All’s fair in love and war, Mother. All’s fair.”

The next day, she walked into the plant and resigned, explaining that she was going to be married and that her mother had already left for Garden City, New Jersey, for another position, this time a job in retail.

“She got bored with the computer. Said she needed people. She sends her deepest regrets and apologizes for her abrupt departure, but the job starts next week. Just mail me her last paycheck and W2 forms, and I’ll forward them to her when she gets a permanent address. Thank you for your kindness, cousin Jimmy, and good luck in Mexico.”

Simple, clean, no complications.

Well, you can’t really call what happened in June a complication. Some might even call it poetic justice.

“My, your garden is beautiful, sweet pea.”

“It is, isn’t it. Look how nice the beets are coming up.”

“Your roses are as beautiful as you are, real prizewinners. I sure am puzzled, though. How did those forget-me-nots get in the rose beds? Did you plant them?”

“Yes, ah-h, they’re Mother’s favorite.”

“Too bad she isn’t here to see them. Have you heard from her lately?”

“Yes, got a letter from her yesterday. She loves Garden City. I guess you could say she’s blooming where she’s planted.”