The world happens so quickly these days, it's not surprising to see so many things designed for immediate gratification. From McDonald's to Wal-Mart, we're a fast food nation par excellence, constantly on the prowl for cheap and easy solutions for everyday needs and desires.

But of course there's much that's lost in the Faustian bargain of the cheap drive-thru lunch. (Note how even language is shortchanged, when we don't even have the patience to finish spelling words in full!) It may taste good at the moment, but relying on the path of least resistance in the long run kills whatever deeper, more complex experiences (culinary and otherwise) have been shut out because they lack such an immediate payoff.

I started thinking about all this after a fascinating conversation I had a few months back with Ann Haaland, a painter and printmaker whose work I didn't entirely trust at first.

When I initially received some information in the mail from her, the work looked interesting—colorfully abstracted views of trees in a forest, which read almost like jewel-toned passages of stained glass. They were (and are) beautiful, but my hesitation at the time arose from the very immediate likeability of the works, and the consistency with which she had executed them. Obviously she had talent, I thought, but would these works go anywhere, or stay in this single, successful gear?

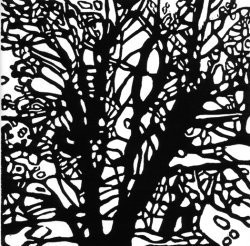

In a studio visit with Haaland a month or two ago, I was impressed to see that she'd been pushing the formal language of the forest paintings further, delving into the abstract web created by the gaps between the overlapping branches, which now press the limits of pure abstraction—it's become almost impossible, at first blush, to see either the forest or the trees. With this increased removal from her immediate subject, she's complicated the color schemes as well, fulfilling one of the latent promises of the earlier work by allowing the originally negative space between the trees and their branches to dominate the canvas, manifesting as positive forms in their own right. (In fact, she starts each work by laying in the color of the 'negative' spaces first, filling in the increasingly abstracted trunks and boughs afterwards.)

In our conversation, Haaland expressed some concern about the negative reactions she'd received from a number of her family and friends, who didn't like this new, more abstracted work. "They didn't understand the new work, and kept asking me, 'Why don't you keep doing the trees that we like?'" she told me. Not that she doubted the artistic value of what she was doing for a minute—it was just disconcerting, it seems, to have such negative feedback from her closest circle of admirers.

For my part, I was happy and quite relieved to see her continue to grow and develop as an artist, and to resist becoming too comfortable with a formula that was, after all, pretty successful. Failure to push beyond what comes easily and settling into a formulaic groove is a phenomenon seen quite regularly in what might best be termed more 'commercially lucrative' art. Left to their own devices, I suspect many (if not most) people would just as soon look at something bright, or pretty, or otherwise easy on the eyes, and not have to think about moving out of their own aesthetic comfort zone at all.

But staying in that safe territory, where things are recognizable and easily assimilated, is a prescription for fast-food art. Look at the enormous success of Thomas Kinkade, the self-proclaimed "Painter of Light." His tacky, saccharine views of a nostalgic America, of lighthouses and formulaic villages that never existed in the first place, are cranked out by the thousands mechanically using silkscreen on canvas, with his signature glowing highlights added in by hand by a small army of trained monkeys. (You can pay extra to have the glowing bits laid in by the master himself.)

This is the antithesis of meaningful art, despite what the legions of Kinkade's admirers may tell you. It's disingenuous in the extreme, a way of making pretty fluff in response to what is a real need: the craving for aesthetic experience, the drive that makes us want a visually interesting environment in which to live and work. Instead of a rich, nuanced, aesthetic response, he gives his audience a fast but empty experience, lacking in any challenge to the viewer. Serious, honest art demands not only a talented artist, but an audience that is open to engaging it as well, on its own terms.

It's always the hardest to see what's right in front of you, the art of the contemporary moment. By contrast, we have no problem accepting art of the past that was once considered outrageous, difficult, or downright offensive. Look how the crowds flock today to any exhibition with the word "Impressionism" in the title, while back in the day, newspaper cartoonists ridiculed the work of Monet, Degas, and the rest by advising that pregnant women not be allowed to endanger their health by viewing the art of this disturbing new movement.

The only way to go about it is to challenge yourself—maybe not continuously, but at least on a regular basis. Take some time now and then to look at artwork that isn't immediately pleasurable to you, that inspires some initial discomfort, even. Think about it. Look at it some more. And only after that can you truly make an honest judgment of the work's value, and in the process, hopefully you'll escape the artificial diversions of fast food art that feeds the eyes but not the mind.

Ann Haaland is opening a small exhibition this month at the Cunneen-Hackett Arts Center in Poughkeepsie featuring a few of the recent paintings, along with a number of linoleum block prints, she's been making, based on the same abstracted imagery. The prints make explicit the graphic dimension of the paintings, and open yet another window on the serious, complex process Haaland engages in her art. Also exhibiting will be Emma Crawford, showing a series of complexly layered and collaged prints. Crawford is a member, along with Haaland, of a group of local artists who meet regularly in a printmaking studio to do their work and exchange materials, experiences, and advice. Ah, the joys working alongside sociable and supportive creative people! But that will have to be the subject of another column one of these days.

Ann Haaland's "Works on Paper and More" and Emma Crawford's "Synchronicity" are on view December 1-31, 2006, at the Cunneen-Hackett Arts Center, 9 and 12 Vassar Street, Poughkeepsie. (845) 486-4571; www.cunneenhackett.org. An opening reception will be held on Saturday, December 2, from 6 to 8pm.