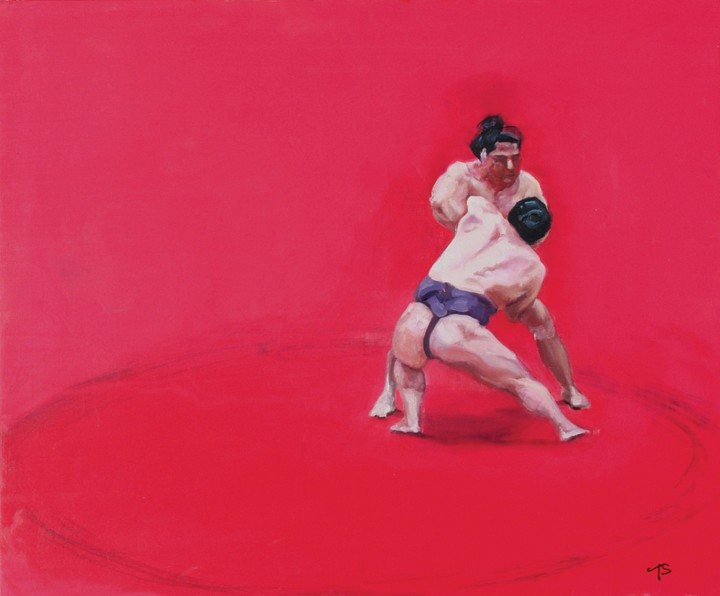

As this year’s artist in residence at Kingston’s Trolley Museum, Temre Stanchfield is painting landscapes inspired by Kingston Point Park, located not far from the museum on the Hudson River. These pastorals, which suggest a luxuriant, if slightly disquieting, languor represent a departure for the artist. Formerly a photorealist who explored issues of gender and sexuality in her images of female and male nudes, Stanchfield has been moving toward a more painterly style. Her series of Japanese-inspired female heads, which she showed at galleries in Kingston, Beacon, and Rhinebeck in 2007 and 2008, turned conventions of the Japanese feminine ideal upside down, with their exaggerated coiffures, blurred faces, and carefully rendered accessories. Her more recent series of head studies showcases the visceral nature of paint: Images of blandly beautiful women are transformed into grotesques by the loose, luscious application of red and pink paint and erratic scraping. In one monumental study, the canvas has been turned on its side so that the head rests heavily on the ground, as if suffering from a very bad hangover.

Born and raised in Alaska, Stanchfield spent her young adult life in the Seattle area before earning an MFA at the University in Arizona in 2000. Her paintings of overweight, middle-aged, nude men, depicted as cavorting cupids, and young cowboys wearing nothing but cow masks were shown at the Pima Community Art Gallery in Tucson and in Los Angeles. In 2001, Stanchfield and her husband moved to Japan, where both taught at the Kanazawa International Design Institute, an affiliate of Parsons School of Design. After arriving in the Hudson Valley in 2007, they bought a house in Kingston, where Stanchfield paints in an attic studio and teaches art to children. Her landscapes will be shown at Donskoj & Co. in Kingston from July 4 through 25. (845) 338-8473;

www.donskoj.com. Portfolio: www.temrestanchfield.com.

Growing Up in Alaska

I was born in Kodiak. My dad was a commercial fisherman. He was out fishing for many weeks on end. We moved from Kodiak to Dutch Harbor, which is the biggest fishing port in the US, to be closer to the industry, after my mom went an entire year not seeing my dad. Dutch Harbor is a little island out in the Pacific Ocean that’s a two-hour plane ride from Anchorage.

I was there until the middle of high school. It was very isolated and sheltered but an amazing place to grow up. There were wild blueberries growing everywhere. We had our fishing poles and our big boots. It wasn’t cold like the interior of Alaska, because of the Gulf Stream. But the elements were outrageous: There were 14 hurricane cables tying our house into the bedrock. It was quiet, and you had to rely on the community. There was one TV channel, which showed the Iditarod in the winter. There were no paved roads. There was a rec center, which showed movies twice a month, one grocery store, and one or two restaurants.

I think there’s something about being an outsider. I’ve always loved traveling. Coming down to the Lower 48, it was very much like I was outside looking in on this culture. That’s what I do with my paintings. I’m often an outsider looking in, taking things apart and questioning them and studying that.

Investigating Paint

I’ve been spending a lot of time mixing paints and looking at color. Most of the [landscapes] seem to be taking place in spring and summer, a time of fertility and transition, [although they’re] not about reflecting on what I see out there; it became more about subjective content. I like them to be a little acidic, slightly off. My goal for [the large works] is to stay as loose as possible, because they’re more of a mystery and not everything has been given away. I like paintings that ask questions more than tell facts.

Painting Kingston Point Park

This is the first time I’ve approached the landscape. I’ve wanted to for a long while, so it was a neat opportunity that I was asked to be the artist in residence at the Trolley Museum. I started visiting Kingston Point Park in February and have taken lots of photos. Originally, I was interested in the park because it’s gone through such a transition. You don’t have the ferry bringing people in; geographically, it’s kind of on the side of Kingston now. And then walking in the park and seeing these very mysterious areas overgrown with bushes and grasses, you can see originally there was something else there.

Narrative has always been central in my work. In graduate school I did a lot of narratives with the figure, male and female. At this point I am really enjoying talking about space and place. We can tell we’re at Kingston Point Park: There are barbecue grills, and this kind of dwarfed human activity goes on amid the larger evolution of nature. I start with the photograph and I like [the paintings] to go farther away from that, to where there’s just the suggestion. I’m taking from the literal and abstracting it a bit.

American Beauty

[The latest head studies] are about questioning how I’m working with paint. I started mostly with magazine or catalog images, images that are generic in a sort of American Beauty way. With paint they’re transformed and start to look like puppets or dolls. Even the gender becomes ambiguous.

They’re not delicate, they’re not feminine, except perhaps in the color. There is almost a feeling of applying makeup. It looks very raw, some people say violent, although I don’t mean to do that. They became these big mountains of flesh. I like the idea of using this form to get to the landscape. I started mixing up these tones I’d used in my palettes of flesh and applying them to the landscapes. It’s exciting.

Becoming an Artist

As a child, I took making art for granted, especially because there was so little to do. My sister and I didn’t have very many opportunities; there were no teams or special classes. We were both very creative, and it was very open-ended. I didn’t begin to value [making art] as a serious pursuit until my third year of college, when I went off and studied at the Studio Art Center International in Florence, Italy. I was with all these kids from New York, who were these completely foreign creatures. They brought a level of rigor and seriousness [to the making of art], and I thought, “I can approach this and do this as a serious pursuit.” That shifted my view. I went from being an art minor to an art major, and at that point I decided, “This is it, this is what I’m going to do.”

Sabbatical in Japan

[My husband and I] lived in Japan for six years. I was teaching art, studying Japanese and ikebana (traditional flower arranging) and having children. We lived in Kanazawa, a small city on the west coast that’s called the Old Kyoto. It’s got a beautiful cultural center and a samarai district, and they just put in the 21st Century Museum. They’re constructing more high-speed rails to go into the city, and it was interesting to see the changes. While in Japan, I was not compelled to paint, although I did make these teeny-tiny, dinky paintings, which were the beginning of moving away from my earlier photorealist work.

Culture Clash

Initially [while living in Japan], it was really neat just to experience being an other. It was fabulous and scary, to be on the bus alone and be the only one who looked different. In the States we’re much more free-flow and less organized. Our clothes and bodies are large and free and open. The way people in Japan take up space is much more minimal and practical. I found myself constantly trying to minimize the space I was taking up, which affected how I walked, sat, everything.

You’re this totally different creature. Sometimes it was claustrophobic and sometimes it was okay. There’s also this way of thinking that’s non-linear. It would baffle us. You see it in their storytelling. We go from A to B to C to D and give an argument, and then there’s a resolution. In Japan the narrative is experienced in a more poetic, cyclical form.

Here we put the individual first, we strive to be unique and different. In Japan the emphasis on the group was in some ways very contrary to what I would have liked. When my kids were at nursery school, for example, there was often the lack of being able to say your opinion or express yourself freely. On the other hand, one of the things I loved was that if I lost my child’s mitten, someone would have placed it just where I would see it upon returning to the place four days later. It’s a very secure, family-oriented place.

Landing in the Hudson Valley

[While in Japan my husband] Scott was job hopping and was offered a number of jobs throughout the world, including [jobs in] Turkey and Morocco. But for family reasons, he took the job he was offered at Bard, which is working with foreign students at the conservatory. I’ve always wanted to live in New York, and it’s been really neat to be so close to the city.

The Hudson Valley is an amazing place. The arts are so rich over here. It’s very different from the West Coast. There’s an intensity here that I just love. [The arts are] not questioned. In Japan, it’s valued, but the creative people are few and far between. Like everything in Japan, it’s very compartmentalized.