When you visit Jennifer Donnelly in her Dutchess County home, high on a hilltop with swoony views of the Catskills, you may wonder if you’ve entered some other century. Roses tumble from urns, flanking an entry with neoclassical columns and marble floors, where an inquisitive greyhound greets visitors. Two Hudson River-style canvases lean against walls, still unframed. An upstairs hall sports a sectional street map of 18th-century Paris.

“It was built in the 1980s,” says the author, a striking blonde with expressive dark eyes. She explains that the house was gutted by a Wall Street tycoon and once played party house to a rock star’s entourage. The Hudson River canvasses? Painted by a former tenant in Brooklyn. The map? It’s research.

Donnelly has a talent for straddling centuries, as her just-released Revolution (Delacorte, 2010) attests. Ostensibly a young-adult novel, this tale of two rebel teen girls, one from contemporary Brooklyn and one from revolution-era Paris, is sure to find fans among adult readers, especially those who like their historical fiction brimming with messy, exuberant life.

“It’s very important to me that history lives and breathes—I don’t want it to be cod liver oil,” says Donnelly. In her hands, it’s more like Red Bull.

Revolution has an impeccably hip soundtrack (Natalie Merchant, another local century-straddler, appears in the acknowledgments). The novel begins in the dark throes of privilege. Seventeen-year-old Andi is a fiercely talented guitarist, her passion for music all that prevents her from drowning in grief and guilt after the death of her beloved younger brother. Overmedicating, flirting with suicide, and ignoring her studies at an elite private school, she’s whisked off to Paris by her absentee father. When she opens the secret compartment of an antique guitar case and finds the diary of Alexandrine Paradis, a teenage street performer swept up in the Terror, her life takes an unexpected and dangerous turn.

The Paris catacombs become the path through Andi’s private hell, accompanied by a hunky Tunisian-French cabbie named Virgil, who shares Andi’s talent and introduces her to the underground music scene—literally—at a hallucinogenic venue known as The Beach. (Yes, it’s real, though Donnelly was “too claustrophobic” to venture an illegal entry on her Paris research trips; the official tour of the catacombs’ boneyards was enough.) Since Revolution’s epigraphs are drawn from The Divine Comedy, Virgil’s unlikely name is no accident. “Dante was also in a dark wood—he was older than Andi, in his thirties, but also in despair, on the verge of suicide,” says Donnelly, adding with a grin, “If you’re going to ride somebody’s coattails, it might as well be Dante.”

All three sections of The Divine Comedy end with the word “stars,” and when Virgil leads Andi above ground, she lifts her face to the night sky. “I want to tell teens, you will get through this dark time—there is light, there are stars, and you will see them again,” asserts Donnelly, with a fervor that sounds authentically adolescent. Indeed, she says quietly, “I struggled with depression at that age, and have struggled with it subsequently.”

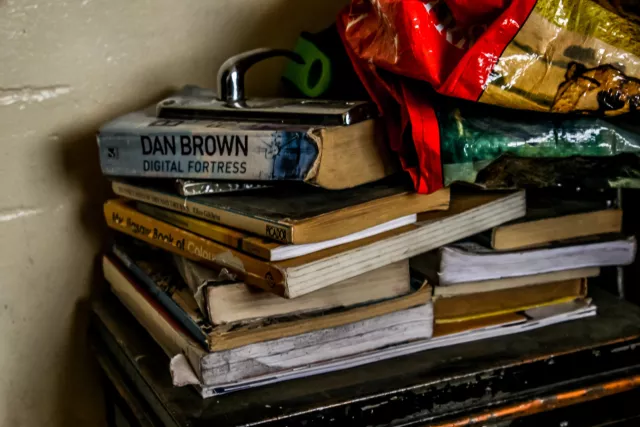

Who was her own Virgil? “So many writers, teachers, professors. They gave me the key to the castle, opened my eyes to the power and solace of literature,” she says. “I was so sustained by reading, by the idea that generations of writers had been there before me, that every time I went into a library and took a book off the shelf, there was a master class in my hands.”

The master class on Donnelly’s shelves has a very eclectic curriculum. There are research books with titles like Atlas du Paris Souterrain; five different editions of Ulysses (“James Joyce is my desert island guy”); The Invention of Hugo Cabret; Stephen King stacked atop E. M. Forster. “I grew up on a diet of mass and class,” says Donnelly. “I loved A Woman of Substance. I love, love, love Stephen King. Never apologize for what you read.”

Or what you write. Donnelly’s Rose trilogy (The Tea Rose, The Winter Rose, and the forthcoming The Wild Rose) is a sprawling Victorian epic that ranges across several continents. Written with a research-hound’s eye for detail, they’re escapist page-turners, warmly blurbed by the late Frank McCourt and Barbara Taylor Bradford.

Donnelly started writing The Tea Rose at 24, between day jobs at J. Crew and Saks. She struggled for 10 years, “getting up at four am, working on weekends, not seeing people—always, always, always trying to get a book published.” Finally, she sent a whopping 1,100-page manuscript to literary agencies, including Writers House. Agent Simon Lipskar told her, “You can write, but you need a lot of work on structure and narrative drive.” He mentored her for two years until they felt the book was in saleable shape.