Flights of Fancy

[]

Halfway between Paul La Farge’s weathered barn and colonial farmhouse in Red Hook, a small promontory tops a stone wall. It’s his habit to start every workday by standing there, gazing over a broad meadow rimmed by a stream on one side and a tall fringe of trees on the other. A morning meditation?”

“More like a morning celebration of getting out of New York,” says the acclaimed novelist and Bard professor. He and his wife Sarah Stern, co-artistic director of the Vineyard Theatre, bought the house in July. It was literally a dream come true—the couple had rented the farmhouse for two blissful summers. “We used to wish we could stay here forever,” La Farge says, beaming. “And now we can.”

Someday they may even have time to finish unpacking. It’s been a busy fall for La Farge, whose new novel, Luminous Airplanes, debuted in October, garnering raves from the New York Times Book Review, Publishers Weekly, and others. Usually a novelist’s work is done long before publication. But La Farge, whose previous books include The Artist of the Missing (FSG, 1999); Haussmann, or the Distinction (FSG, 2001); and The Facts of Winter (McSweeney’s, 2005), has launched Luminous Airplanes in two different formats: a traditional print novel and a spectacularly ambitious online “immersive text,” to which he is still adding content.

The immersive text would doubtless fascinate Luminous Airplanes’ never-named narrator, a ‘90s-era computer programmer and erstwhile graduate student who leaves San Francisco to clean out his dead grandfather’s house in the Catskills, where he spent a series of summers while growing up. When he reconnects with neighbors Kerem and Yesim Regenzeit, a Turkish brother and sister who were—despite their families’ ongoing feud—his best friend and first crush, past and present collide in unpredictable, possibly dangerous ways. Also in the mix: twin mothers, an absentee father, the evolution of flying machines, and the Millerite cult who predicted (and dressed for) an 1844 Rapture that never occurred. When La Farge finishes uploading a decade’s worth of prodigious imaginings, the immersive text will contain many more storylines.

La Farge’s wire-rim glasses, silvering beard, and unruly dark hair suggest one of Chekhov’s eternal students. He’s a gracious host, offering a selection from “our large but idiosyncratic collection of teas” before sitting down at a kitchen table covered by a cheerful yellow ProvenÇal tablecloth to discuss his work.

He comes by the writing gene honestly: His father and stepmother are both fiction writers, his mother a psychoanalyst. Though his parents divorced when La Farge was just three, they maintained Manhattan apartments within walking distance to ease his commute. He often spent summers at his father’s country house near Windham, the locus in quo for Luminous Airplanes’ fictional Thebes, New York. (With such actual mountain hamlets as Athens and Cairo, it’s hardly a stretch).

La Farge is an old French name, and though the ancestral La Farges (including a Napoleonic soldier who moved to Haiti during Toussaint L’Ouverture’s revolution) were Catholic, the novelist’s family enrolled him in the Ethical Culture School. “I was raised nothing,” he says with a laugh. “I was raised a New Yorker; that is a religion.”

He lived in Manhattan for 17 years, then went to Yale, where he studied comparative literature, spending his junior year in Paris. “At the end of that time I had been happy enough for long enough that I thought it was possible to write fiction,” he says. One of his early stories evolved into an unfinished novel called O. “I would spend two hours every night after dinner, drinking wine and writing fiction. The thing just took off. As soon as I started it, it was like touching a power line. I thought, There’s no way I’m ever going to want to do anything else. This is what makes me happiest in the world. And that remains true.”

Nevertheless, he enrolled in an academic graduate program at Stanford, dropping out after a year to move to San Francisco. “I wanted a more intense involvement with fiction,” he says. “I didn’t want to share that energy with being in graduate school.” O, which he now concedes was “written in Pynchon’s shadow,” had swollen to 500 pages, and LaFarge was only halfway through his plot diagram. He felt stuck and frustrated.

Then he read Charles Bukowski’s short novel Pulp, and decided to spend two weeks writing something completely different. He completed the first draft of The Artist of the Missing in 15 days. “It was like the catch released from a spring,” he says. “Then I spent two years rewriting.”

The Artist of the Missing and its follow-up, Haussmann, or the Distinction, put him on the literary map. Set in Paris during the massive facelift engineered by its historical title character, Haussmann has the large-canvas sweep of a nineteenth century novel, with a distinctive postmodern conceit: La Farge bills it as a translation of a 1922 work by an obscure French poet and “tiny metaphysician” Paul Poissel.

The pseudonymous surname’s “origins are shrouded in mystery,” says La Farge, “but I do like the way it sounds.” He always refers to Poissel in the third person. “He’s a he, and I’m the scholar, the researcher who looks into his activities,” he explains. Haussmann’s afterword reproduces daguerreotypes from the Bibliotheque Nationale’s photo archives, concocting a deadpan faux biography for Poissel. La Farge even created a website for his alter ego, including “archival recordings” of him reading his work. Did La Farge provide his voice, or was an actor involved? “Also shrouded in mystery,” he says cheerfully.

Paul Poissel gets top billing on the bookjacket of The Facts of Winter, with La Farge credited as his translator. Its form is a series of prose poems, allegedly the dreams of various Parisians in the winter of 1881, plus a rambling scholarly afterword by the “translator.” La Farge, who had just moved back from San Francisco to a post-9/11 New York, found a welcome escape in the multileveled fiction.

“I feel like life is really complicated,” he asserts. “There’s so much going on in our experience, so many different layers going on all the time. Everyone who’s writing fiction seriously is trying to be honest about something, even when we’re simultaneously lying like crazy and trying to entertain the reader.”

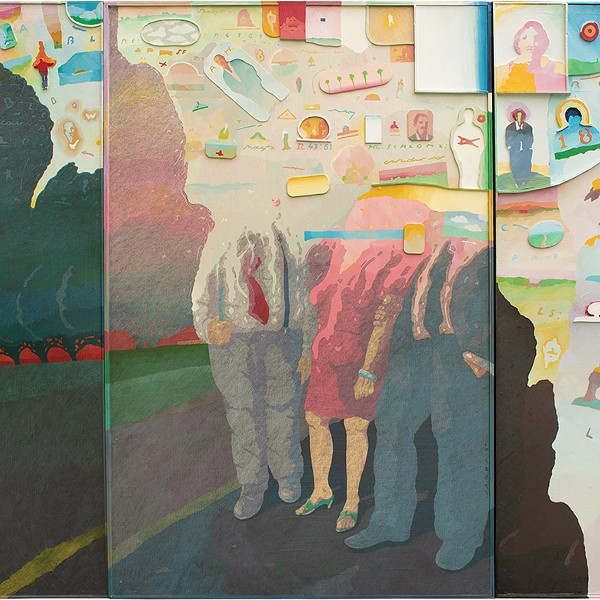

McSweeney’s has just released a new edition of The Facts of Winter with illustrations by Walter Green; at a recent reading at Hudson’s ArtsWalk, La Farge refers to it fondly as “literary Stilton.” He adds, “You write what’s going to make your heart glad, and in my case, that happens to be 1881 prose poems by an obscure French writer, followed by a lengthy literary afterword.”

Or an evolving immersive text about a prodigal son’s return to the Catskills. La Farge has a kid-in-a-candy-store enthusiasm for his new venture, and can’t understand why he seems to be flying solo. In a press release for Luminous Airplanes, he writes, “One of the themes in the novel is the invention of the airplane, and I keep saying to myself, OK, I’m the first one to do this—does that make me more like the Wright Brothers, or like the guy who invented the giant steam-powered bat, this monstrous thing that never got off the ground? The truth is, I still don’t know.”

There was a brief vogue for “hypertext fiction” in the 1990s, but most of these were experimental in language as well as in form. Luminous Airplanes cross-breeds an emerging technology with a beautifully written traditional narrative. As its narrator says of the sole book he’s brought to Thebes, “Reading a novel, especially a contemporary novel, with its small stock of characters and situations, felt like being stuffed into a sleeping bag: it was warm and dark and there wasn’t a lot of room to move around.”

The immersive text unzips the sleeping bag, adding a vast pile of options. “There’s a lot of trial and error involved,” La Farge admits. “Some of these sections have been in my computer for 10 years—I’m finally able to put them up there, so I can rearrange them.” Readers can also rearrange, reading sequentially and returning to browse various links, or entering links to side stories as they go along. It’s akin to the difference between playing an LP, with its preordained sequence of cuts, or downloading the same songs along with a huge trove of previously unreleased material, which you can play in whatever sequential, intuitive, or random order you choose.

LaFarge’s website contains a link to www.luminousairplanes.com, under the tongue-in-cheek header “Potentially Endless.” Eventually, the immersive text will include the entire 82,000-word novel, plus at least twice as much new material. “It contains the main story which runs through the book and goes on past the end of it, plus a few major side stories,” says La Farge. “When those are told, I’ll know I’m done.”

The imaginative challenge of organizing such an enormous canvas seems dizzying, but that’s just one hurdle. “You also need to have mastered some fairly tough programming language, or work with a programmer,” says Paul La Farge. “I could not have done this myself, but I’ve been a programmer, so I know enough about the technology to know what’s hard and what’s easy. I want the interfaces to work. Even if it turns out to be a giant steam-powered bat.”