A knock on the door of Sydney Cash’s studio is answered by a wiry 80-year-old with an intense, inquisitive gaze, the same one he focuses on his art, which is sprawled out on the work table behind him. His mind still burning bright in the sixth decade of his career, he excitedly asks if the visitor wants to see what he’s working on now. “In a lot of ways I think I’m a research scientist,” he proclaims. “That’s what I’ve always done and that’s the most exciting part of the process for me.”

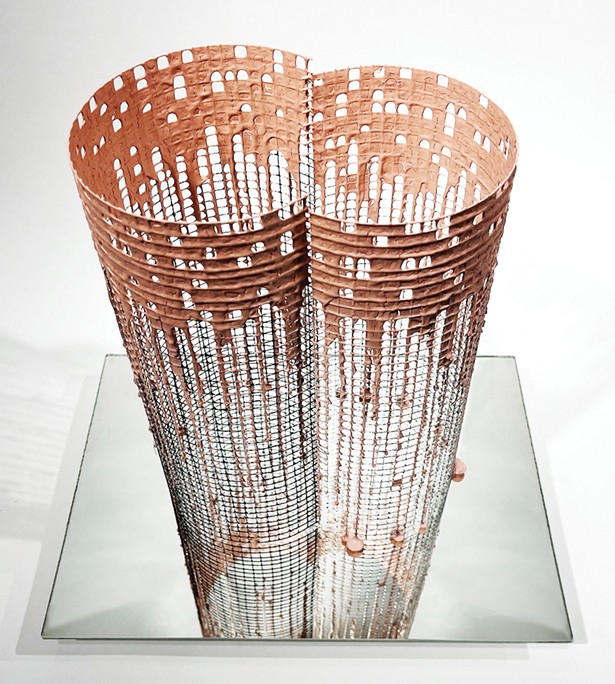

Currently, Cash is interrogating hardware cloth, a prosaic metallic gridded material. He’s applying wall paint to it in various ways—pouring, brushing, repeatedly dipping, poking, blowing—to see what happens. He observes that “there is nothing more representative of contemporary art than the rectilinear grid,” adding that “this work provides a convergence of engineering, architecture, and mathematics.”

The goal of this inquiry, like most of the others he has undertaken, is to produce art that carries meaning beyond its material presence. In a world that is increasingly virtual, Cash is scientifically addressing the empirical reality of the work he is making in an effort to reveal, however fleetingly, a glimpse of transcendence. His way to locate meaning in art both for himself and the viewer is to perceive the unseeable in the seen.Cash’s mother noticed that her boy liked to make things—he was clever with his hands. She took young Sydney to the Detroit Institute of Art for Saturday classes and had a workbench built for him. At Wayne State University, he first studied metallurgy but ended up getting a degree in mathematics. His current studio—with every wall, shelf, and available surface teeming with works in process jostling for attention with pieces from as much as 30 or 40 years ago—certainly looks like a place where an artist operates. But as you listen to Cash describe his practice, his scientific framing seems to make some sense even as his workplace backgrounds a portrait of the artist he truly is.

Born in the Basement

Cash moved to New York City in the 1960s. A resourceful go-getter, he made a deal with his super to use a room in the basement of his building as a studio. There, he further developed the sculptures he had begun making in Detroit fashioned from castings of antique Gargoyle carvings. Soon he found a buyer at Bloomingdales who was interested in selling the sculptures retail. Sales went well and eventually Cash opened a shop called Gargoyles in Greenwich Village. He had begun his career as a professional artist.Cash feels that he has “great permission in the material world, that [he] is intimate with materials.” Working with glass became the focus of his artistic practice as he got involved with convex mirrors. Cash liked the reflected distortions they made. He is largely self-taught and is constantly experimenting with new ideas. Cash is also blessed with what he describes as a “gift,” which enables him to visualize an unfolding process in exacting detail, “almost like watching a video in his head.”

Moving to the Hudson Valley with his family in the early 1980s, Cash is perhaps best known for his innovative glass work slumping flat glass into dimensional forms in an electric kiln. (Slumping is a technique in which items are made in a kiln by means of shaping glass over molds at high temperatures.)

His art has been shown in respected galleries extensively and found its way into various collections, including the Corning Museum, the Museum of Art and Design, and the Museum of Modern Art. Along with his Marlborough home studio, he has another about a mile away that houses larger works. Recently, he rediscovered large glass pieces there from the early ’90s that he had completely forgotten. Cash admits that he is somewhat impatient and has no interest in repeating himself.

Slumping Toward Beauty

Around 1980, Cash started working with nichrome wire, which is stable at high temperatures, malleable, and strong. He used it in his process of slumping glass with surprisingly beautiful results. “If an artist is focused on looking for beauty, they are taking the wrong approach,” Cash says. “Beauty arises on its own, you can’t force it.” Each day in his studio is a foray into the unknownable guided by his granular knowledge of the properties of the materials he manipulates.His breakthroughsculpture from this body of work, The Tri-fold, was envisioned in a dream. The process the dream revealed began with a triangle of flat glass positioned over a triangle of nichrome strung from a steel support, all placed in a kiln. Cash recalls that in waking life, he witnessed, through a peephole in his kiln’s wall, the sculpture’s formation: “pulled by gravity as the temperature of the kiln rose, the glass started moving downwards.” The supple central cup of the sculpture formed and the three elegant supporting legs stretched toward the kiln’s floor where they folded gracefully into feet. “It was like magic,” he says. “After setting everything up, I didn’t touch a thing.” The fully emerged sculpture became a kind of Holy Grail for Cash. He went on to make several distinct variations on this theme using different kinds of glass, working at different scales, and modifying the underlying structure, each iteration achieving a different expression of what Cash calls “wonder.”

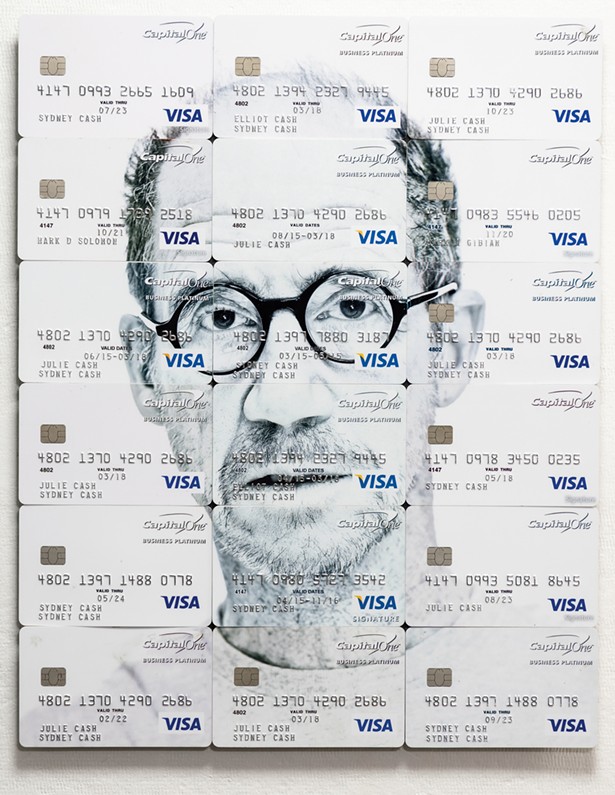

Over the past decade, Cash has worked with lights, glass, and mirrors to fashion pieces that generate intricate, interacting patterns of light, reflection, and shadow on surrounding walls that create a fascinating, abstract, site-specific chiaroscuro. His black grid patterns, in oil over portraits, some photographic, others reproductions of historical works, bring out hidden dimensions of the persons depicted. Cash has also investigated pattern-making for its own sake, devising tools to manipulate paint in ways that are intricate yet spontaneous and highly energized. He has photographed, enlarged, and painted antique etchings highlighting the skilled hand work employed in their original making thus bringing the past into the present without irony and with respect, while eschewing nostalgia. He has even done a self-portrait combining individual credit cards each, with a portion of his face imprinted.

Visualizing the Ineffable

On the studio work table is a piece with two partially closed gridded cylinders opening to each other. Pinkish paint of slightly differing hues, values, and viscosities has been poured over them. Some of the squares of the grid are covered by the paint, others only partially, some not at all. The cylinders rest on a mirror. Beneath the mirror, they are continued for a few inches, creating the illusion of passing through the glass. Cash states that this piece is the most finished and personally satisfying so far from his currently emerging body of work. He goes on to say that while contemplating it, he felt a sudden burst of kindness. Kindness toward himself, self-acceptance, but also kindness in a more generalized sense.Cash was reminded of the long, silent Buddhist retreats he has often attended, where the ineffable sometimes becomes visual. Sometimes, in the studio, a flash of electricity will move up his spine. “Everything gets a bit luminous,” he quips, adding a touch of humor. “It tells me to pay attention to what’s going on, this is important.” But being important isn’t it. Instead, it’s the experience itself, unmediated. “Unmediated! Everybody’s got to come to art that way,” Cash exclaims. In that moment, he had uncovered something immeasurable: a direct experience that for a wordless, unquantifiable moment that opened his heart and perhaps would do the same for others. What will the next experiment bring?