AMMAN, JORDAN, JULY 30

I don’t bother to check the weather. What would be the purpose? Hot is hot. I’ve been told it will be even hotter once I get to Iraq. The streets wind and plow their way up and down the many hills that make up Amman, as my taxi driver attempts to find the offices of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UN-HCR) Iraq Operation. It is my last day in Jordan before flying to Sulaimaniyeh. I’ve just come from picking up my Syrian visa from their embassy, which was very easy to find. My last task of the day is to gather information about the internally displaced Iraqis, and as my driver makes one phone call, takes another series of turns, and makes yet another phone call, I sense this is not his usual terrain. We pull onto a tree-lined dead-end city street wall-to-wall with modern buildings and I spy the UNHCR sign—the only identifying insignia visible on the nondescript office building. My driver, oblivious, begins to make a U-turn as I hand him the fare and hop out.

Although it is four years to the month that the UN headquarters in Baghdad was destroyed by a suicide bomber driving a cement truck loaded with explosives, killing 23 people and injuring over 100, the memory is still fresh among UN officials throughout the Middle East. Security greets me even before I enter the building, where, once inside its cooling shade, I soon hear the clacking of high heels on tile floors. Anita Raman, associate reporting officer for the UNHCR Iraq Operation, appears and takes me to her office. Her eyes are obscured by huge dark sunglasses, à la Jackie Onassis, which offer protection from the midday sun streaming in the windows next to her desk. She is dressed in a flowing sleeveless black-and-white chiff on dress, showing more skin than I am used to in this repressed part of the world, where many women glide to and fro swathed head to toe in synthetic heat-retaining fibers. I have been told to wear shirts that cover my elbows, especially when going to interviews, and have come to conclude that the men here must be so lacking in self-control that for a woman to reveal more could cause her harm. And yet, I think to myself as I don my own sunglasses—the glare literally hurting my eyes—here is this modern woman modeling freedom to my newly repressed

and sweltering self.

“We do have a presence in Sulaimaniyeh, and compounds in Baghdad and Erbil,” says Raman. “There has been significant growth in IDP numbers, especially in Sulaimaniyeh, near the Diyala borders.” IDP stands for “internally displaced persons,” the term used for the hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who have had to flee their homes due to the sectarian violence unleashed by what Raman calls “a mixture of ethnoreligious factional and political violence.”

With Baquba as its capital, Diyala is one of the 18 governorates that make up Iraq. It connects the governorate of Sulaimaniyeh with that of Baghdad, and is considered a “Little Iraq”—a microcosm of the country, consisting of a Shiite-dominated provincial government and security forces (due to its majority Sunni population sitting out the elections), a healthy Kurdish presence on its northern border with Sulaimaniyeh, and a heavy concentration of al-Qaeda operatives. A minimal US troop presence in 2006, combined with the unintended consequence of surge efforts that has seen both Sunnis and al-Qaeda forces flee Baghdad for Diyala, has turned the governorate into one of Iraq’s major hotspots and caused even more IDP movement—this time extending farther north into cities within the three northern governorates of Kurdistan that, according to Raman, “form the nucleus of the IDP communities.”

“Most of the IDPs in the north are ‘scattered urban,’” says Raman. “Because of the restrictions on entry, a significant proportion of the IDPs are people from central or southern Iraq who own property inside the KRG [Kurdistan Regional Government area].” Others came for employment reasons. “The displaced tend to gravitate toward urban centers. However, with the volume of displacement throughout Iraq and within the north, there have been a number of camps for the newly displaced rising throughout the country. The camps are, in some instances, just spontaneous settlements, which are receiving aid distribution but are not yet established as camps along international standards.”

According to the most recent “Cluster ‘F’ Update” (I kid you not)—a biweekly compilation of the most recent information on IDPs within Iraq collected by the UNHCR—in the 16-month period between February 2006 and June 2007, a total of 1,011,870 Iraqis were displaced. A regional breakdown of “newly displaced” families during that same period shows 25,368 families displaced from northern Iraq, 78,984 from central Iraq, and 64,645 families from the south—almost 170,000 families forced from their homes.

A further breakdown shows that after 2006, 47 percent of IDPs originated in central Iraq, with approximately 180,000 from Baghdad alone. Another 38 percent originated in the south, and 15 percent in the north. Since 2006, says Raman, “we have been witnessing massive movements out of Iraq’s major urban areas, mostly in central Iraq.”

RUNNING FROM SADDAM

Most of the violence in Iraq at the beginning of the invasion tended to be politically based. After the Samarra bombing, religious divisions seemed to manifest as the root cause of the violence being perpetrated in a country where, if you ask Iraqis, there was general tolerance and acceptance of the “other.” Many did not care to ask if one was Shiite or Sunni, and intermarriage between the sects was common. With most of today’s violence targeting the urban centers with the clear intent of debilitating them through terror—areas that were suffering from infrastructure collapse long before the invasion in 2003—it appears likely that whoever is planning the violence is simply adding fuel to a fire that was already burning. These

previously weakened areas did not, and still do not, have sufficient supplies to maintain municipal networks. The sewer system in Sadr City, Baghdad’s poorest district, was in dire need of repair before Coalition troops set foot in Iraq. Use of generators was a daily event in many places, and unemployment, now reportedly risen to astronomical proportions, was already high under Saddam.

The largest group of displaced in the pre–February 2006 time period, says Raman, is actually the pre-2003 displaced—those who fled or were forced from their homes under the regime of Saddam Hussein. Th e main reasons for this displacement, according to the latest Cluster “F” Update, were “human rights abuses” and “internal conflict along political, religious, and ethnic lines”; additional factors would include the Iran-Iraq War and, later, the Gulf War—the aftermath of which saw Saddam retaliate against the 1991 Shiite uprising in the south by attempting to destroy their economic livelihood, purposely draining the southern Mesopotamian marshes and horribly suppressing the Shiite population. “Construction of dams in central Iraq; competition over land and natural resources; as well as pursuit of Saddam’s ‘Arabisation’ policies” were also reasons for mass movements of Iraqis. The Arabisation policies included the infamous Anfal genocide, which took place between February and September of 1988 and saw a military campaign move from the southeastern section of the Kurdish north to the northwest in six months, clearing the land by killing tens of thousands of Kurdish civilians and Peshmerga—the Kurdish guerilla organization that now constitutes Kurdistan’s military force (which is doing a remarkable job of providing security in the north)—and then enticing

Arab tribespeople to move there via relocation subsidies. According to Raman, “The pre-2003 displaced were, prior to the current conflict, mostly arising out of human rights abuses in northern and southern Iraq. They are estimated at 1.2 million and represent IDPs coming out of Anfal and the draining of the marshes.”

RUNNING, RETURNING, AND DESPERATE TO LEAVE

A second, smaller group of pre–February 2006 displaced came from the movement of people between 2003 and 2006—families leaving as a result of time-bound or predictable military operations where people were given “time frames to vacate and then reenter urban areas. This was the movement out of Falluja and Ramadi,” says Raman, where the US advised residents to leave before they began their attack on insurgents. “The overwhelming majority of them have returned to their homes.”

Then there are the refugee returnees—Iraqis who fled the country while Saddam was in power who have now voluntarily reentered Iraq post-invasion. Figures are inconclusive at best, with some governorates not counting returning Iraqis for months at a stretch and others not counting them at all. However, of the number of Iraqis repatriating northern Iraq since the invasion in 2003, Raman says, “there are no figures, but it is well in excess of 300,000. And that was as of March 2006.” Maps on the wall in her office show arrows representing movements of people into and out of certain areas of Iraq. When closely questioned as to the numbers represented by these arrows, Raman says that figures based on aid distribution as

per the public distribution system maintained by the Ministry of Trade show an influx of 330,000 people returning to southern and central Iraq beginning in 2003 and continuing in a steady stream through 2004. The majority came from Iran and represent both Kurds and Shiites who had run from the brutalities of the former regime. Kurds returned to the north and Shiites to the center and south. Across the country, the number of returnees could easily be close to one million.

On Raman’s map there are also three small triangles located in a vast expanse of open desert. These represent three different refugee encampments. Currently, 1,200 Palestinians live in one of these encampments. Iraq’s Palestinian refugee population, once estimated at 34,000, has dropped to approximately 15,000. Real numbers are hard to come by because many of those who once lived in Baghdad and were protected by Saddam have been subjected to extraordinarily brutal violence by hostile militias. Some were able to leave Iraq in the early days of the invasion, but after Syria and Jordan closed their borders, those who did not make it out are now trapped. “It is a forsaken location,” says Raman who visited there recently. “It is blisteringly hot. They have no access to schools. They have tented shelters. Snakes and scorpions are common. We are working with the Red Cross to improve the sites, but [this

encampment] does not function and that is universally recognized.”

Since January 2005, 197 Iranian Kurds have lived at a second, similar encampment. The third encampment holds 137 Sudanese from Darfur who once lived in Baghdad and worked as skilled laborers. Also targeted by militias, they now live in “extraordinarily harsh conditions in a very violent location that is difficult for us to access,” says Raman. “I find that the refugees tend to become a bit of a byline in the Iraq war.”

It suddenly all comes back to me as to why I am here—having wondered at the airport in Amman if I was truly crazy for returning to this place of war.

But the war is not apparent in Sulaimaniyeh. Th ere are limited checkpoints, men with scarves wrapped turbanlike around their heads and wearing flowing zoot-suit-type pants cinched at their ankles, smooth, clean black-asphalt roads, and signs of enormous growth everywhere—new construction of more smooth, clean black-asphalt roads, hotels, condominiums and other housing, the almost-completed University of Sulaimaniyeh, even a newly opened gelato parlor. How could it be that I was at all tentative about coming to this place that has once again captivated my aff ection so immediately, so intensely?

I have gained entry to this part of Iraq with the help of two friends, Nathan Musselman and Anna Bachman. Anna and I met in Baghdad in the weeks before the war in 2003. We had both entered Iraq under the umbrella of the now-defunct Voices in the Wilderness (VITW), an Iraq-awareness-raising, antisanction organization founded by long-term peace activist Kathy Kelly. At the time, VITW was the only known group bringing delegations of people into Iraq. Meeting up months later during the segment of a larger speaking tour Anna had arranged in her community in Washington State, she and I made plans to return to Iraq. In February 2004, while at Kennedy Airport waiting for Royal Jordanian officials to remove the body of a

man who had died on the flight over from Amman from our delayed plane, Anna spotted her friend Nathan Musselman, who just happened to be on our flight.

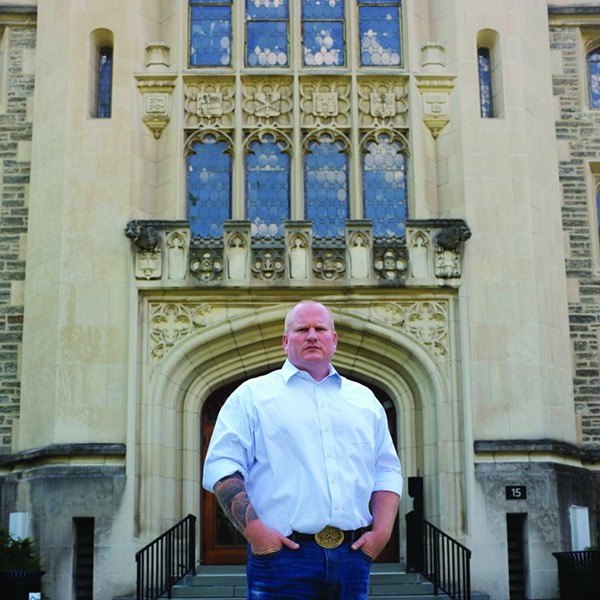

Today, Nathan is the Prefect and Deputy to the Chancellor of the brand-new American University of Iraq in Sulaimaniyeh (AUI-S), and he has arranged my letter of entry—required to gain admittance to Iraq. Anna lives in Sulaimaniyeh working as a project manager at Nature Iraq (NI), an Iraqi NGO focused on the protection and restoration of the environment and the cultural heritage of Iraq. Under the guidance of its director, Iraqi-born Azzam Alwash, NI’s primary project has been working to restore Iraq’s extensive marshes. Once the third-largest wetlands in the world, most of the marshlands were purposely destroyed by Saddam Hussein’s regime in the 1990s in retaliation for the Shiite uprising during the first Gulf War.

Anna introduced me to Alwash in January 2005 in Amman. I was on my way to Baghdad to cover the first Iraqi election. The three of us shared tea in a downtown restaurant. The combination of Alwash’s PowerPoint presentation, with its amazing satellite, aerial, and ground-level images showing the before and after effects of restoration efforts, his fiery, impassioned stories of a resilient, determined people—the Marsh Arabs—whose culture his father had introduced him to as a child, and his obvious reverential affection for their culture left me captivated. “One benefit, one positive story that may be coming out of the liberation of

Iraq is the fact that we’re working on resuscitating a 7,000-year-old culture,” said Alwash with eyes aglow. “There is a clay tablet from 3,000 BC documenting reed construction methods that are still being used today.” When the last US bomb fell back in 2003 (maybe even before), Alwash, working along with others, began encouraging the taking down of the artificial barriers that had literally drained the ancient marshes, allowing them to be reflooded.

Born in Kut, Alwash moved with his family to Nassiriya, on the edge of the marshes, when he was nine months old. They lived there for eight years before moving to Basra and then to Baghdad. After being pressured to join the Baath party, Alwash, a Shiite, moved to the US in 1978. But it was the marshes—8,000 square miles of wetlands the size of the state of Massachusetts—that called him back.

Alwash’s words remain permanently etched in my memory: “It is one of the few places on Earth where human beings have completely integrated themselves into their environment. Talk about sustainable! The life of the Marsh Arabs is completely dependent on the reeds. They are the skeletons of life, [as is] the water. Water feeds the reeds. The Tigris and Euphrates are headquartered in the mountains of Turkey and northern Iraq. Snow falls, spring comes, snow melts. This humongous amount of water comes rushing down in the spring. Between February and May, 70 percent of the water flow occurs. It comes rushing in with silt and clay, bringing life—timed perfectly for the coming of the reeds from hibernation, the fish coming up from the Gulf for spawning, and the migration of birds from South Africa back to Siberia. The reeds feed the water buffalo. People use [the reeds] to build their homes, furniture, to feed their fires.”

The silt and clay brought by the yearly rush would push out the brackish water left over from the previous year and create islands made of reeds and mud that accumulated over generations and expanded the marshes. Some of the islands, explained Alwash, are sprung loose by the spring influx of water and air, and left to float freely in the marsh lakes. This rush of water historically also brought with it pollution, which was filtered out by the marsh reeds and allowed cleaner water to flow into the Persian Gulf. Saddam’s drainage, which included the building of dams in the north, destroyed massive areas of the marshes. Before restoration efforts began in 2003, polluted water could be found six to seven miles out into the Gulf.

Today, 60 percent of the marshes have been restored, thanks to the “New Eden Team” headed by NI and Iraqi and Italian experts. They have recently released their “New Eden Master Plan for Integrated Water Resource Management in the Marshland Areas.” Sponsored by the Italian Ministry for the Environment, Land, and Sea, it represents over two years of work by NI, Italian partners, and various Iraqi ministries. The plan will help Iraqi legislators plan and addresses issues such as improving the efficiency of water use, restoring the environment, regional economic development, flood control, and community building for returning refugees and displaced peoples.

Working under self-stated goals such as improving the capacity of Iraq’s institutions to protect its environment; developing a database of environmental conditions and trends focusing on water resources, ecology, and biodiversity; promoting the sustainable use of Iraq’s environment and resources; respecting and balancing the traditional use of the environment by indigenous inhabitants, and preserving wildlife and biodiversity, NI oversees projects that include monthly monitoring of water flows in and out of the marsh rivers and a census of the number and distribution of water buff alos in the marshes of the three southern governorates. NI has conducted biannual summer/winter surveys of biological and physical variables such as water quality, macrophytes, phytoplankton, zooplankton, macrobenthos, marine life, and birds at 62 sites within six governorates in southern Iraq.

With offices in Basra and Baghdad, NI was encouraged by its successes to open an office in Sulaimaniyeh earlier this year and, at the request of the Iraqi Ministry of Environment, to extend these seasonal surveys to the Kurdish regions using funds provided by the Italian government. Anna invited me to stay at the newly opened office/house of Nature Iraq in Sulaimaniyeh, and I arrived in time to participate in the start of the first six-week-long survey, which will encompass 30 sites and involve extensive animal and plant surveys and water-quality monitoring at selected dry and wet sites, including a few located on the Darbandikhan and Dokan reservoirs.

WORKING TOGETHER

After sleeping a good part of my first day in-country and making introductions to the 13-plus members of the survey team, we all went off early the next morning to the second choice site of the day: Biyari, a small mountain village on the border with Iran that has a centuries-old stream emanating from an underground spring. The original survey site we were supposed to go to on the Iran/Iraq border was closed off to us by the military due to insurgent activity.

The Biyari site was wooded and cooler than Sulaimaniyeh. Seated on blankets under the spacious arms of the trees, families were gathered to picnic and beat the summer heat.

A mixture of Kurds and Shiite and Sunni Arabs, the NI’s survey team of biologists, chemists, and geologists stands in stark contrast to the brain drain that is decimating central and southern Iraq. A few of the Shiite and Sunni staff are among the displaced, having had to flee their places of origin, and some have family who have scattered to Jordan, Syria, Switzerland, and farther. One man has yet to see his 10-month-old grandson because the child is in Syria.

The team quickly scattered and went to work. Some measured water quality, sediments and benthic invertebrates, while others took to the hills to photograph the flora and fauna. I was free to mingle with the families who beckoned to me to join them, drink tea, and take their photograph. One family up the hill had brought a sound system, and Kurdish music flowed among the trees. A rock wall acting as a buffer between the picnic area and stream housed colonies of hundreds of leaf-camouflaged moths with orange underbellies. Although we were so close to the border we could have been technically in Iran, I had difficulty believing this

was Iraq. Wherever we were, there were no signs of war. However, as we readied to leave a few hours later, a woman preaching Islamist dogma to a large group of women and girls, all apparently enraptured by her speech, was pointed out to me. It was not rapture but brainwashing, the Kurdish members of the NI team informed me. The Kurds openly despise the Islamists. I was told that this woman and her disciples were most likely members of Ansar al Islam—a radical splinter group of Islamist Sunni Kurds that promotes jihad and is known for using suicide bombers against Kurdish targets. “Ansar al Islam was kicked out by the Peshmerga and the US,” I was informed by our extraordinarily observant and intelligent young

Kurdish biologist/fixer. “They go in and out of Iran at will.”

We passed a number of checkpoints while making our way up the mountain—some made up of Kurdish police, some of Kurdish border guards, others Peshmerga or Kurdish government forces. At one checkpoint women in uniform were working alongside the men.

SULAIMANIYEH, KURDISTAN, AUGUST 17

I have been here in Sulaimaniyeh for over two weeks and have hiked, swum, and traversed some of the region’s more spectacular sights while tagging along with the survey team. Having come here to report on the effects of the war, guilt pervades my being—I have not been shot at once this trip. Of course, its not been all fun and sun. The members of the team—all have cameras, all experts in their fields—work practically round the clock, either out collecting

data from the lakes, rivers, and dry areas within Kurdistan, or back at the office/house organizing and analyzing the data. Or, in the case of Haidar Fishman, dissecting the fish samples he has collected. Or, in the case of the water study team, analyzing the water samples for levels of different planktons. For the most part, they spend a good part of each day in full sun with temperatures hovering at 100 plus.

This sort of work, on this level, has never been done in Iraq before. They are not only pioneers, but also incredibly brave men. (Chronogram cannot publish photos that show their faces for fear they will become targets.)

Just about all the survey team members have said they believe that Iran and al-Qaeda are behind the violence in Iraq. Most have said they don’t want the US troops to leave Iraq. On the day Fox News reported that the Bush administration planned to declare Iran’s internal army, the Iranian Republican Guard Corps (IRGC), a “terrorist” organization, thus leaving the IRGC open to having their assets frozen—not to mention subject to attack by the US without the consent of Congress—just about all of the survey team’s members told me they hoped

the US would go to war with Iran and wipe out the present regime there. Some said they wanted America to replace Iraq’s Prime Minister Maliki and install an Ayad Allawi type—someone who would kill Sunni and Shiite equally and not single out one sect for punishment over the other. When Maliki’s visit to Iran was aired on TV, the repeated showing of him holding hands with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad nearly incited a gentle riot among them. “Th is is proof that Iran now runs Iraq,” said one, others nodding in agreement.

But no bombs have been exploding. I don’t recall hearing even a gun go off. The only shouts I’ve heard have come from crowds of people watching localsoccer games, although I did hear my first ambulance siren tonight. The central souk area, a seemingly endless maze of shops, has been nothing but teeming with people and goods of all kinds. I’ve been to an art opening, gone bowling with “the guys,” eaten at a Chinese restaurant (where an American peace-activist-filmmaker-posing-as-a-journalist told me, not once but twice, that I should die because I believe there are good things happening in Iraq along with the bad), and taken a three-hour drive through thriving towns on the way to the burgeoning and modern city of Erbil. The only alarm that’s gone off was within me, and it was in relation to the lack of a female presence on the streets in these smaller towns. Men are everywhere—but no women. I don’t think I have ever experienced that before.

I suppose it has been risky being here. I’ve been swimming in remote and not-so-remote mountain lakes and rivers, and climbed down into a dangerous but stunningly beautiful gorge where I did come close to being incapacitated—by heat emanating from the surrounding boulders. Touching them literally singed my fingertips. As part of our day-off picnic, I gave swimming lessons to some of the guys. Admittedly, it was a bit of a challenge attempting to teach eight grown men, whose languages of Arabic and Kurdi are alien to my tongue

and who are terrifi ed of the water, how to swim. Later, while photographing them playing soccer, I thought they might be thinking of eliminating me when the ball inadvertently went over the cliff and down a 30-meter rock scramble to a sheer drop-off into deep water. “Lorna! Lorna!” went the war cry. The only strong swimmer, I was volunteered to retrieve the ball—not once, but three times.

Another day, I left a meeting to go get some water. In Kurdistan, men don’t allow women to do much on their own—a polite tradition masking a deep-rooted subjugation of women. NI’s superfriendly driver, Shorsh, who speaks no English, followed me to the grocery store. As we mounted the steps together, he gestured insistently that he would purchase the water. I gently tugged on his shirt in an attempt to hold him back. As Shorsh ordered the water bottles and took out his wallet to pay, I thought, I am going to kill you. At the very same

moment—literally—he pointed to a toy handgun on the counter and said slowly, in pure, clear English, “I am going to kill you.” When I told him I was thinking the same of him, we both laughed—tears streaming down my face.

And that is about the closest to danger I have come while here.

But I am in Kurdistan. In Iraq—a country that has been watched, dissected, critiqued, used and abused by the media, terrorists, insurgents, and agendists left, right, and center—this place called Kurdistan has been virtually ignored. The opinions of its people have not been aired. The good going on here does not exist for those who do not want anyone to know that among the rubble, horror, and death that exists in other parts of Iraq—yes, it exists, I know that for a fact—the din of construction, the pains of growth, and the sounds of laughter also exist.