As we enter the end of summer’s bounty here in the Hudson Valley, luxuriating in local berries, stone fruits, and tomatoes, it’s a good time to start thinking about where much of our fruit comes from for the rest of the year. We’re accustomed to having access to so many varieties of fruit in stores that we may balk at the prospect of eating only locally, fearing that it will mean nothing but applesauce all winter long. But once we learn the full range, quality, and beauty of the fruit that can thrive in our area, we see that there’s no sacrifice at all—quite the opposite, in fact, as anyone who has forked over big bucks for a few pints of berries can understand. And it’s important to separate fruit production from agriculture in our minds. For an aesthetically minded homeowner, many of the fruiting trees and shrubs are as beautiful as any of the ubiquitous inedible ornamental plants around most of our houses. By using more edibles in our landscaping, we can make a major change in our fruit consumption patterns and have more beautiful yards to boot, with little of the work associated with gardening. Simply put, we can have our pretty flowers and eat them too.

Any serious tomato fan will agree that there’s no point in eating them fresh any time other than high summer—they’re simply not the same thing. Canning them whole or in sauces is the solution for the long, dark, tomatoless nine months of the year, and we’re okay with that; it’s just the nature of tomatoes, and pleasure is what eating them is all about. Other than apples and pears, not much else grown here can be stored for very long without also being canned or frozen. So we dutifully capture sunshine in jars by making jams, jellies, and chutneys, and by freezing bags of berries for eating and baking all winter long. It’s what our ancestors did out of necessity, and we must accept that a real effort to eat locally in our region is going to require applying the Tomato Rule to all our fruit; preservation at the peak of ripeness for subsequent use in cooking is the future as well as the past. The simplest way to make this reality a blessing—a source of flavorful delight, rather than a limiting burden—is to increase the variety of fruit that we grow.

Equatorial Hudson Valley

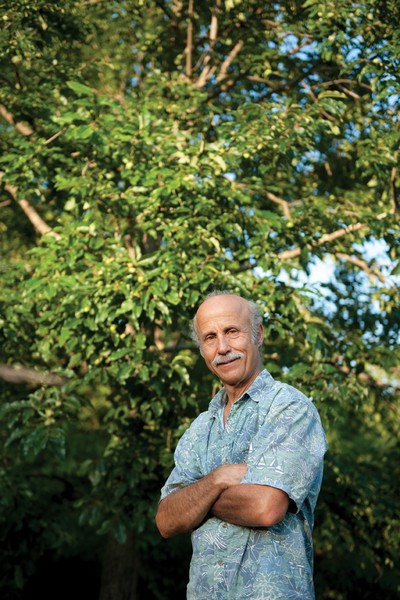

Lee Reich is a writer, teacher, and consultant who lives in New Paltz. He has multiple graduate degrees in horticulture and soil science, and tends a remarkable “farmden” (“more than a garden, less than a farm,” from his website) on a modest plot south of Rosendale. His most recent book, Landscaping with Fruit (Storey Publishing, 2009), describes about 40 of his favorite fruit-bearing plants from an edible, aesthetic, and maintenance point of view. His focus is on maximizing variety, flavor, and beauty while minimizing the labor required to tend it all. While his property is home to a huge variety of edible species, he is realistic about the amount of time an average homeowner can devote to growing food: “It has to fit in with your life, or it doesn’t work,” he says, and tries to steer people toward the easiest and tastiest options to begin with.

These include his favorite, blueberries, which need little upkeep and fruit prolifically in addition to providing beautiful fall foliage and winter stems. All they really require is netting to keep the birds off as the fruit ripens. He’s also a big fan of lingonberries, lowbush blueberries, and strawberries as ground cover, and planting hedges of Nanking cherries (a pretty, shrubby variety) and seaberries, which are extremely easy to grow, have lovely silvery leaves, and produce copious orange berries that taste similar to orange juice spiked with tropical punch. Another excellent choice is the pawpaw, which grows to a handsome tree with shiny dark green leaves and produces fruit that looks like mangoes and tastes a lot like vanilla pudding. They’re the only member of a family of tropical fruit trees (including cherimoya and soursop) that can grow in our climate, and produce the biggest indigenous edible fruit in North America. If we add hardy kiwis, which grow on vigorous vines that look lovely on a trellis or arbor, and the passionflower vine, which has gorgeous flowers and produces perhaps the greatest of all tropical fruit—the passionfruit—we can see that growing our own doesn’t mean giving up on the lavish flavors of the Equator. It’s easy to grow nuts, too, especially hazelnuts and chestnuts, and Reich likes his Buart nut tree, a cross between a butternut and a Japanese walnut.

There’s No Tilling

It may be counterintuitive, but these choices are actually much more logical than, say, apples. Reich stresses that it’s virtually impossible to grow apples organically around here; the pests are simply too many. Other traditional trees, like plum and peach, are a bit better, but still require diligent pest control. Pears—Western and Asian—do very well, and Reich is an even bigger fan of the American persimmon; easy to grow, attractive, prolific, and tasting like “dried apricots dipped in honey and spice,” is another favorites Currants, which should be much more popular, are another excellent choice for producing copious fruit in limited space. They come in a dazzling variety of colors, and can grow in partial shade, making them ideal for planting under larger trees.

Reich’s secret to low-maintenance gardening of all kinds is a no-till approach to the soil. It’s a literally top-down approach that he explains in his 2001 book Weedless Gardening (Workman Publishing Company). The main premise is simple: Nature fertilizes the soil from above, without tilling, and plants don’t require any further interventions on our part. All we have to do is prepare the ground—layer newspaper to kill grass or weeds, add a couple of inches of compost, plant, and then mulch. He proudly points to the beds in his garden, saying “for 25 years all these have gotten is an inch or two of compost every year, and they’ve never been walked on.” (Walking would crush the delicate crystalline matrix that exists in healthy soil.) The soil is black and crumbly, and the vegetables are prospering. He estimates that he spends about five minutes a week weeding, and the garden is roughly 2,000 square feet. Besides being harder work, tilling also activates weed seeds by exposing them to air and light. Tilled soil uses 60 percent more water than untilled and burns organic matter faster, requiring more applications of fertilizer. “Tilling the soil is a major source of CO2 entering the atmosphere,” Reich explains. “If you really want to dig, go mark off a piece of ground somewhere and go dig in it when you feel the need.”

Not-So-Strange Fruit

Ethan Roland teaches and practices permaculture at the Epworth Center in High Falls. His goal is “to establish local food security and deliciousness in a time of dramatic change.” He talks about each separate polyculture planting as a metaphor for the movement as a whole; as they grow and spread outward, he will mow less and less space between them until they connect to form a complete fabric. Diane Greenberg is co-owner of the Catskill Native Nursery in Kerhonkson. She agrees that people should grow more fruit even if they don’t plan on eating it: “Why would you not want a hedge that flowers, then fruits? It’s so much more interesting to look at, and if you don’t eat it, the birds can.” Instead of using invasive plants from big-box stores for our foundation plantings, she encourages people to come and explore the many beautiful and edible alternatives.

These and other experts provide advice, classes, and assistance in making some positive changes to the flora around our homes and doing it in a way that works for us. We don’t all need to become self-sufficient overnight. But if we make choices that gently move us in that direction, relying less on imports, spending more time (and less money) connecting with our food—and enjoying luscious fruit along the way—we can spend less, eat better, and have enviable yards. What’s not to like?

RESOURCES

Lee Reich www.leereich.blogspot.com

Ethan Roland www.appleseedpermaculture.com

Green Phoenix Permaculture www.green-phoenix.org

Catskill Native Nursery www.catskillnativenursery.com

Ethan Roland’s Top 5 DIY Permaculture Books

1. Gaia’s Garden by Toby Hemenway

(2009, Chelsea Green)

2. Edible Forest Gardens, Volumes I and II by Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier

(2005, Chelsea Green)

3. Food Not Lawns by Heather Coburn Flores

(2006, Chelsea Green)

4. Landscaping with Fruit by Lee Reich

(2009, For Dummies Press)

Ethan Rolands’s Top 5 Regional Permaculture Nurseries

1. Catskill Native Nursery, Kerhonkson

2. MiCosta Nurseries, Columbia County

3. St. Lawrence Nurseries, Potsdam

4. Tripplebrook Farm, Southampton, Massachusetts

5. Oikos Tree Crops, Michigan