It looks like any normal construction site. A pattern of foundations line trenches cut deep into the earth. Workers are busy handmixing and applying fresh cement to the newly minted cinder blocks that line and cover the crude broken stones of the foundation. The blocks will grow to form walls of a housing complex for dozens of families. Except this site is anything but normal. Aside from its location in Kurdistan, in northern Iraq, just over the Azmar Mountain range from Sulaimaniyeh, a young child recently lost three fingers here when an unexploded unidentified piece of ordnance left over from the days of the Iran-Iraq war blew up at his touch.

If not for this tragedy, the story reads like a “things gone right” tale of Iraq. The housing under construction here in Samsawa is meant for 1,500 Kurdish internally displaced persons (IDPs), forced to leave their homes as part of Saddam Hussein’s retaliatory “Arabization” of Kurdistan after the First Gulf War. In addition to draining the southern Mesopotamian Marshlands in an effort to remove Shiite Marsh Arabs from the region and destroy their 7,000-year-old culture, Saddam’s campaign forced Kurds from Kurdistan while at the same time enticing Arabs north to take the Kurd’s homes, virtually replacing them—ethnic cleansing tactics that have created a tense legacy in today’s already intense Iraq.

The Kurdish IDP families are a minute representation of the estimated one million Iraqis displaced by Saddam’s regime pre-2003 and the current conflict. At present, these families live in a makeshift shanty village immediately next to the construction site, which in the 1980s and `90s was an Iraqi military base. Located close to the Iranian border, it housed the infamous Peshmerga—Kurdish freedom fighters who date back to fall of the Ottoman Empire, include women within their ranks, and whose name literally means “those who face death”—who currently provide security to northern Iraq. The site is also home to munitions, the exact amount yet to be discovered, buried when Iranians threatened to overrun the area.

A BURIED WAR

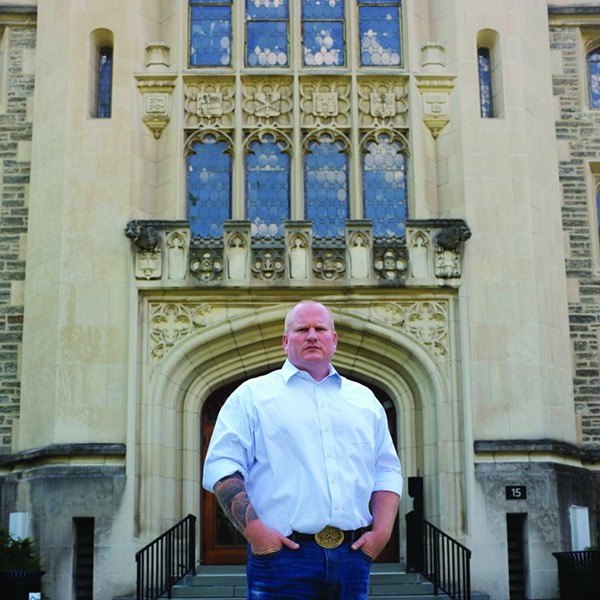

“So far we’ve removed 240 mortars, a combination of 105 and 122mm artillery projectiles, type 63 107mm Chinese rockets, and mortars sized 120 down to 60mm, an assortment of RPG tail heads, fuses, and other items, all ready to be fired save for a fuse,” says Mick Beeby, on-site technical field manager of the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) Iraq. A neutral and impartial international humanitarian organization with fundraising arms in both the US and UK, MAG has been working to remove such leftovers from various conflicts and wars—former and current—in 35 countries (out of an estimated 82 known to be mined) since 1989.

Mostly funded by institutional donors, governments, and foundations and other charities, MAG’s income—$8 million in 1995, growing to $62 million by 2007—is project-specific, meaning the funds can only be spent on predetermined projects and activities. However, it also benefits from public donations and fundraising campaign like a recent “Celebrity Shoe Auction” in the UK. Such “unrestricted” income enables it to react quickly to emergencies, or to fund projects where other funding isn’t available.

MAG’s work in the Shamsawa is funded by the US State Department program Grants for Conventional Weapons Destruction and to Assist Injured Conflict Survivors, overseen by the Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement (OWRA). To help reduce the reported 5,751 casualties worldwide from explosive remnants of war and landmines in 2006, OWAR “approved more than $4.4 million in grants to 32 organizations to destroy conventional weapons, landmines, and explosive remnants of war, and to assist those who have been permanently injured by conflict,” from its projected $123 million budget for conventional weapons destruction in fiscal year 2008.

Beeby’s grant obligations stipulate that his six Mine Action Teams and three Community Liaison Teams operating within the Sulaimaniyeh sector must work on 3.9 million square meters of land per contract period, which is one year in this case. “Donors just don’t give money for nothing. I have to actually physically clear 650,000 square meters, plus another 3.52 million [need] to be demarcated. I also have to destroy a minimum of 4000 items ranging from mines to UXO (unexploded ordnance), which includes such items as unexploded bombs, rockets, missiles, mortars, and grenades.” Beeby’s work—either demarcation efforts or actual ground clearance—must have an immediate effect on 10,000 beneficiaries, people who can once again use the land. Direct beneficiaries from clearance efforts at the construction site number 1,500, and 3,000 indirectly. Pointing to one of his team leaders Beeby says, “He has to destroy 770 items per month for 10 months to meet his team’s quota. This is not a problem at all.” After all, 500 “live” items were removed from just one pit among many excavated in the construction site, in addition to what is called “scrap”—spent ammunition cases, projectiles, and mortars with no explosive fill, and three Katyusha missiles. “You do get a lot of explosive harvesting in this part of the world,” says Beeby.