Endless Connection

[]

What alchemy goes into making a poet? Though every writer’s cauldron is idiosyncratic, certain binding ingredients recur: an unusual childhood, a teenage infatuation with Romantic verse, an abiding passion for language and music. And then there’s the unpredictable quicksilver element—perhaps a short stint on a deep-sea research vessel.

Poet Jeffrey Yang made his debut with a literal splash. His first collection, An Aquarium (Graywolf Press, 2008), winner of the PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award for Poetry, is an alphabetical sequence of 55 poems. Though the organizing principle is a marine bestiary, the creatures between Abalone and Zooxanthellae include not just Barnacle, Clownfish, and Dolphin, but Google, Intelligent Design, US, and Vishnu; clearly Yang’s aquarium has bigger fish to fry.

Graywolf just released his second collection, Vanishing-Line, an equally brilliant suite of seven longer poems on a staggering range of topics, both historical and personal. It’s a densely textured work, its magisterial sweep more suggestive of an elder statesman contemplating mortality than the cheerful 36-year-old who comes to the door in a slate-gray shirt, jeans, and well-worn cotton slippers. Yang’s bright smile is framed by a minimalist goatee; he wears a string bracelet around one wrist, and could easily pass for a graduate student.

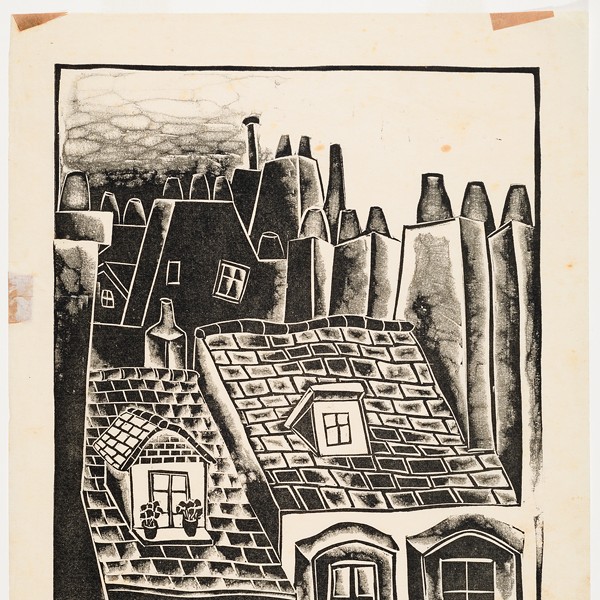

He lives with his wife and two children in a suburban neighborhood near Beacon’s Main Street. Set back from the road, the house is fringed by a row of late-season tomato plants and a small koi pond. Yang’s writing studio is an outbuilding constructed by the former owner as a carpentry workshop, which seems apt: Beautiful things are built here. Walls that once sported hammers and power tools are now lined with overstuffed bookcases. Loose books lie in front of shelved ones in untidy piles, pages bristling with paper scraps and small yellow Post-it notes. Several shelves are devoted to books published by New Directions, where Yang is an editor. The window above his desk frames a breathtaking view of Mount Beacon. Today its peak is obscured by low-hanging mists, clouds curling through trees in a way that suggests Japanese inkwash paintings.

Yang puts in four days a week as an editor, two in New York and two at home. He writes “Fridays, evenings, and other odd scraps of time,” juggling his own poetry with translation projects. Despite the time stresses, he finds that “editing, poetry, and translation feed into each other in a way that’s positive. As an editor, you have to love to read. Careful reading feeds into writing. And translation is the best thing you can do to teach yourself to write. You need to look at language very, very carefully, thinking about every choice you make. You really have to be attuned to what the author is trying to do—grammatically, linguistically, stylistically. It teaches you by slowing down your reading.”

Though the New York Times Book Review called An Aquarium “a first book written from a very high floor of the Tower of Babel,” Yang’s conversation comes from a much more accessible level. His discourse is sprinkled with GenX locutions like “sort of,” “you know,” and a questioning, upward inflection; it’s almost as if he’s abashed by his own erudition, reflexively downshifting to Marianne Moore’s “plain American which dogs and cats can read.”

Not that his verse courts obscurity. “I’m definitely not trying to write something difficult or pretentious. A lot of what I hope is that the music carries the meanings. There’s complexity and simplicity,” Yang says, citing “an Eastern tradition in Japanese and Chinese poetry and arts, especially those influenced by Buddhism: They’re so simple, but a metaphor for everything. Like a circle painting.”

Still, even a moderately well-educated reader may be intimidated by Vanishing-Line’s thicket of literary, historical, and cross-cultural references, not to mention the subtle geometry of the book’s structure. Yang’s work rewards careful rereading and pondering, and perhaps a few trips to the OED. From “Two Spanish Poems”:

Memory upon memory of stone

wood, tapia, stucco.

linked star dado,

spandrels lead to frieze

each form

follows its intention,

each carving

a hidden glory

Vanishing-Line took shape over a 10-year period. “The concept was always the same, but it expanded and contracted over the years,” Yang explains. He came across the title phrase in Alexander García Düttmann’s Between Cultures, from which he drew the book’s epigraph. Its many possible meanings resonated with him; he enumerates “poetic lines, horizon line, lines of thinking, lineage, blood lines” as some of the things that may vanish.

The opening and closing poems, “Throne” and “Yennecott,” sift through layers of vertical history, calling to vanished cultures in old and new worlds. “Elegy for Ling” honors a family member who took her own life, and “Lyric Suite” was inspired by the death of Yang’s grandmother, who lived with his family during his high school years. Its title comes from an Alban Berg composition, which, Yang says, “shaped the whole book.”

Another poem, “Tide Table,” riffs on a film installation by South African artist William Kentridge. Yang was mesmerized by Kentridge’s stop-motion charcoal drawings: “what he draws, what he erases.” In a bibliographical afterword to Vanishing-Line, he reflects, “This seepage of works into work feels as natural as tar bubbling up in a field—sometimes drawn out through seeking, often unconscious or dreamt, always enigmatic, the way words transform souls into words, word bound to word.” Some lines later, he writes, “Poetry looking back and ahead could be said to have preceded the weblink as endless connection into world-information.”

Yang’s writing process is one of accretion: “First a line, or an idea. A line that turns into an idea, or an idea that turns into a line.” He writes by hand on scraps of paper, or in the margins and blank back pages of books he’s reading, often on the train. “You’re talking to the book—it’s almost like marginalia, the thoughts that come out,” he says of this habit. Next the scraps “migrate to the computer,” where he runs through many drafts, often leaving off for long stretches and coming back fresh.

Yang grew up in Escondido, “this sort of weird place” outside San Diego. His parents emigrated from Taiwan in the 1960s (the family was doubly displaced, having left mainland China in 1948). They spoke Chinese at home until Yang and his siblings “rebelled against it in high school.” The elder Yangs weren’t especially literary, though “they always wanted us to learn” and often gave books as gifts; Yang’s father, an engineer, liked to read wuxia (martial arts knight-errant tales).

Though Yang started reading poetry in high school, his major in college was marine biology. After graduation, he worked at the Scripps Institute Aquarium, feeding fish, cleaning tanks, and monitoring animals. Later he spent four months as a lab assistant on a research vessel above the Galapagos Rift, studying an unusual ecosystem caused by underwater sulfur smokers. He spent most of his time “cutting up animals”—mostly long tube worms—for molecular research, which bothered him. “They were so beautiful,” he says ruefully. The expedition spent two months at sea, then made a four-day supply run (“our cook ditched us in Acapulco,” Yang laughs) and returned for two more months, during which Yang kept a journal and read Moby-Dick. Did this launch his writing career?

“I never thought of writing as a career.” He shrugs. “I always assumed I would be doing something else.” He spent a year teaching English in China, then moved to New York, where he studied at NYU and started working at New Directions’ front desk. He’s been there for 11 years, moving up through the ranks to his current title of editor-at-large. “Working at the press is amazing. I get to help bring all these books into the world,” he says, beaming.

Yang’s translation of incarcerated Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo’s June Fourth Elegies is forthcoming from Graywolf in April; the Dalai Lama just sent in a foreword. In 2009, a year before Liu won the Nobel, Yang translated some of his poems for a journal published by PEN. Larry Siems, director of PEN’s Freedom to Write project, met with Liu’s wife Liu Xia and brought back two manuscripts: a volume of poems exchanged as prison letters by husband and wife, and the June Fourth Elegies, commemorating those killed in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989.

There’s a great deal of buzz about this bilingual publication, since Liu’s poetry, long censored in China, is hard to find in any language. Yang notes that he’s better known as an activist, essayist, and cultural critic—“You really can’t talk about human rights activism without talking about him.” But aside from the handful of poems on PEN’s website, information about Liu’s poetry is largely secondhand. What is it like from a literary standpoint?

“Very intense, bare-boned, concise,” Yang reports. “It’s not the most subtle poetry, but it can’t be separated from the context of what he’s writing about and where he’s writing from. It’s a poetry of witness.”

Yang can now add another Nobelist to his international resume: Swedish poet Tomas Transtromer, whose complete poems he acquired and edited for New Directions, just won the 2011 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Jeffrey Yang folds his legs onto his chair, gazing out at fog-shrouded Mount Beacon. “The way we write is who we are and what we see,” he says. “It goes back so far and crosses different cultures. A lot of what we write comes out of long traditions. You’re not lonely; you’re communing with all these great voices.” And adding your own, in an endless connection.