Music has the power to do many incredible things. Things that other human innovations, like architecture or medicine, as essential as they are, don't quite do. When we've been tamping down our aggression all week and desperately need a release, music gives us the occasion to pump our fist and howl at the moon. When the sun's finally out and the work's all done, it lets us burnish the glow by rolling down the windows and cranking up the jams for the whole world to hear. When we're in the dumpster romantically it picks us up, pats us on the back, and tells us, "There'll be other girls (or guys), kid." And yet another of music's amazing abilities is the way it has of bringing people together. Not just in terms of an audience having a collective experience, but also how it can let two individuals bond. In some instances those two might be musicians themselves, who likely would never have connected otherwise. And in certain cases, like that of Larry Campbell and Teresa Williams, the same pair might be in love with each other as well as the music they make.

"We met at a gig of Teresa's at [New York nightclub] the Bottom Line in 1986," says Campbell, the multi-instrumentalist well known for his time as Bob Dylan's guitarist. "She'd been looking for a pedal steel player to play these country songs she'd demoed for a showcase set, and a friend had suggested me for the gig. This was the tail end of all that 'urban cowboy' nonsense, so without meeting or hearing her I figured, 'Oh, no, another gig with some wannabe country singer.' [The friend] called to tell me she'd dropped off a tape of tunes for me to learn. I asked him what she looked like, and he said, 'Man, she's burnin.'' When we finally met at the club I was, like, 'Wow, yep.' But I was also knocked out by the authenticity when she started singing. I said, 'Wait a minute, this is a real country singer.'"

"And at the same time I was listening to him play and thinking, 'Wait a minute, no one in New York can play pedal steel right. So how is he doing that—and making my songs sound so great?'" recalls singer and guitarist Williams, adding, with a laugh, "But he also had a look in his eyes that said 'trouble,' and I thought, 'I wouldn't touch him with a 10-foot pole.' We didn't see each other for about a year after that, but one night we ran into each other and he asked a friend we were with to let me know his girlfriend had left. And right then, I just knew we were going to be married."

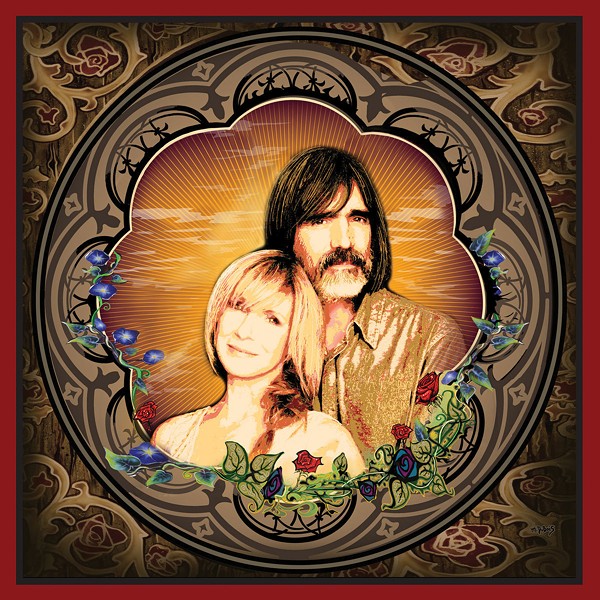

Anyone who's seen and heard the duo perform, in other settings or, most famously, alongside Levon Helm at one of the late drummer's celebrated Midnight Rambles, will tell you: It couldn't have gone any other way. Campbell, the Stratocaster-wielding embodiment of tall, dark, and handsome; Williams, the angelically gorgeous blonde vision with a heart-melting voice to match; their shared pure sound flowing together like two sparkling mountain streams. If there's a First Couple of Roots Americana, it's this one.

Their individual backgrounds go, however, couldn't get more disparate. Raised in Manhattan, Campbell had parents who weren't musicians themselves (although he says his dad was actually a great singer) but had a wildly eclectic record collection that they encouraged little Larry to explore. "They had all kinds of stuff," he says. "Opera, Broadway soundtracks, Hank Williams, Peter, Paul and Mary, mariachi bands, even [crucially] Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music. The raw folk stuff was generally what spoke to me most." But like many Americans he cites February 9, 1964, as the date on which he, at age nine, was bitten hardest by the music bug. "I saw the Beatles on 'The Ed Sullivan Show' and all of a sudden the door blew open," Campbell recounts, with still-measurable awe. "It was powerful, like an opportunity being presented to me. I thought, 'This is something I can do!'" He "devoured" the Beatles' records and those by the other British Invasion bands and traced the roots of their sound back to Chuck Berry and the early rock 'n' rollers and "other stuff that gave birth to rock 'n' roll, like Doc Watson and Bill Monroe. By 1966 I couldn't stand [not yet playing himself]. I got my dad's Sears guitar and started learning how to play from music books and working out songs by listening to records." In addition to guitar, Campbell would go on to master fiddle, mandolin, pedal steel, and an arsenal of other instruments and by the early 1970s was in a band called Cotton Mouth. "Sort of a roots band, but at that time it was too early in New York for what we were doing," says Campbell, who eventually quit the group to take a shot at the big time in Los Angeles. "I went out there because it seemed like that's where everything was happening—but I ended up playing for spare change in Griffith Park." By 1978 he'd bummed his way back to New York, where he found much steadier, better paying work as a session player, cutting jingles and soundtracks by day. By night he became a standout player on New York's by now burgeoning country rock scene, working clubs like the Lone Star Cafe, City Limits, and the Rodeo Bar. He got to know Helm and his Band-mates and other Woodstock players and was welcomed into all-star folk group the Woodstock Mountains Revue. Next came cozy gigs in the pit bands of the theatrical productions "Big River" and "Rhythm Ranch."

Williams, however, had a more direct route to the roots of American music: Her family, who sang and played traditional music when they weren't—and often when they were—working the fields of the seventh-generation West Tennessee farm she was raised on. "I don't remember a time when I wasn't singing," she says. "Our whole family always sang. In church, at gatherings, and around the table after supper, especially. We loved to watch [country legends] Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and the Wilburn Brothers on TV." By her teens Williams had become more interested in theater, and enrolled at the University of Tennessee to study acting. "I thought I could just have a career doing local theater. In Tennessee! [Laughs.] My advisor told me that if I wanted to become a serious actress I had to go to either Chicago or New York," says Williams. She chose the latter, and in 1982 arrived there for an intensive program centering on famed instructor Sanford Meisner's technique. Yet even with the focus on acting, she couldn't keep away from singing. Not long after the move, she joined a group that toured with Country Music Hall of Famer Eddy Arnold. "It was ironic, living in New York and singing back-up vocals for someone who came from about 30 miles away from where I grew up," she says. Williams would in time portray the Carter Family's Sara Carter in the road production "Keep on the Sunny Side" and the documentaries Lost Highway and The Carter Family: Will the Circle Be Unbroken, as well as the title role in the musical "Always...Patsy Cline."

The two were married in 1988, and for the first few years of their union enjoyed stationary bliss. Williams worked in regional theater and Campbell played with Broadway's hit "The Will Rogers Follies." When "Follies" folded in 1993, Cyndi Lauper tapped him as her touring guitarist; next came jaunts with k.d. lang, Roseanne Cash, Elvis Costello, and others. After four straight years on the road, though, Campbell, missing his wife, decided he'd had enough of the traveling life. But not long after that decision was made, there came a phone call: a chance to work with the man commonly regarded as the greatest songwriter of our age, and one of the most influential and immortally iconic artists that history has produced. Would Campell like to play with Bob Dylan? It was, of course, an offer no sane working musician would refuse.

"I turned him down," says the guitarist. "I just didn't wanna be on the road anymore. But then I thought, 'Wait a minute. There's the Beatles, the Stones, and Dylan. The Beatles are gone. The Stones aren't looking for anyone. I'd be a fool for passing this up.' So I called back the next day and said yes—and Dylan's manager offered me more money. He thought I was holding out. [Laughs.]" And so it was that in 1997 Campbell signed on as Dylan's guitarist and multi-instrumentalist, performing with the singer around the world, helping dramatically in the crafting of 2001's acclaimed album Love and Theft (Columbia Records), and appearing in the 2003 film Masked and Anonymous. So what was it like playing with Bob Dylan? "It'd take a whole book to answer that, honestly," waxes Campbell. "There were definitely some moments where it hit me that 'Wow, I'm on stage playing these songs with this guy. I must be doing what I was put on this Earth to do.'" Ultimately, though, the so-called Never Ending Tour began to feel a bit too much like its name, and in 2004 Campbell left. "There were a lot of great things about [playing with Dylan] but the guy really is on this constant road battle, and there's stuff around that that's not so appealing," he explains.

Almost as soon as he'd put down the phone from quitting Dylan's band, it rang again. This time the voice on the other end was Levon Helm's. "Come on up to Woodstock and let's make some music," it said. Come on up Campbell did, to perform in Helm's band and become the musical director of the Midnight Ramble sessions at his barn studio. "The beginning years of the Ramble were always a mess, but it was a joyful mess," Campbell says about the revered series, which, two years after the beloved drummer's passing continues to be held on Saturday nights. "There's always been this feeling that everybody is doing it because they love playing music, and that the audience truly loves being there just as much." At the invitation of Helm and his daughter Amy, Williams entered the fold not long after her husband. "To be playing with the same man who sang 'The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,' a song that meant so much to me growing up, and also made me think of my own daddy when I saw him play Loretta Lynn's father in Coal Miner's Daughter...," Williams says, tearing up a bit at the reminder of Helm's passing. "It's something I never dreamed would happen."

Campbell produced Helm's Grammy-winning albums for Vanguard Records, 2007's Dirt Farmer (a coproduction with Amy Helm), 2009's Electric Dirt, and 2011's live Ramble at the Ryman, as well as acts like Olabelle, David Bromberg, and Jorma Kaukonen, the latter as both as a solo artist and with his long-running band Hot Tuna. "Larry's the best at what he does," says Kaukonen, whose next album Campbell is currently overseeing. "He knows how to bring the magic out while staying away from doing anything forced or inappropriate." Currently, Campbell and Williams are readying their long-awaited debut disc, a preview which reveals a sterling musical mother lode of addictively twangy, upbeat drive ("Bad Luck Charm") and irresistibly heart-snagging ballads (Williams's devastating "Did You Love Me at All").

Believably to those who experienced their nights at the Ramble with Helm, the couple cite their years with The Band's percussionist as the happiest of their musical careers. "When we started playing with Levon at the Rambles, it just was so special," Campbell says. "Not just because we were lucky enough to work with him and all of these other amazing musicians. But because it was a way for the two of us to be together and do the thing we love the most—playing music."

Knowing that, of course, just makes the music sound even sweeter.