It is said that the thick, endless green reed beds and seasonally mobile mud islands that make up Iraq’s southern Mesopotamian Marshlands once nourished and gave shelter to ancient communities born long before the recording of human history. Some scholars claim the marshlands are the location of the Garden of Eden, the birthplace of Abraham, and the site of the great flood where Noah built his ark. World famous archeological sites scattered along the edges of the marshlands hold remnants of the birth of human civilization. Among them are the ancient Sumerian cities of Ur, Lagash, Larsa, Eridu, and Uruk, one of the world’s first cities to house a dense population and home to a king who went by the name of Gilgamesh and resides in history thanks to one of the more famous works of early literature.

It is in this place, the southernmost tip of the ancient Fertile Crescent—where the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers divides and separates into a drainage basin made up of a multitude of small waterways before emptying into the Persian Gulf—that plans are being implemented to create Iraq’s first National Park in an area ravaged by the vengeful acts of Saddam Hussein, who during the closing decade of the 20th century aimed to destroy a 5,000-year-old culture. The proposed Mesopotamian Marshlands National Park will cover an area just under 350,000 acres and contain a core area of 59,000 acres. Known as the Eden Again Project and led by the Iraqi environmental group Nature Iraq, the project’s partners also include the Italian Ministry of the Environment, Land, and Sea, and Iraq’s Ministries of Environment, Water Resources and Municipalities and Public Works. The broad objectives of the national park aim to protect the environment, foster socio-economic development in the region, preserve its cultural heritage inclusive of restoring and protecting from further deterioration all identified archeological sites, and to guide the establishment of ecologic corridors within the marshes along with the creation of an appropriate marshland monitoring and management system.

Creating a national park is a heady goal for an organization that hires body guards to accompany their scientists as they work in the field doing surveys, collecting flora, fauna, and water-quality samples; and cataloging wildlife. And if creating Iraq’s first National Park during a time of war and occupation weren’t enough, discussions regarding the creation of a second National Park have recently begun in northern Iraq’s Kurdistan region, a more secure but equally environmentally devastated area thanks to the purposeful acts of the regime of Saddam Hussein. Although Iraq’s north and south are separated by its heavily populated central region, the lifeblood dispensed from the Tigris and Euphrates links the two regions. Fed by headwaters located in the mountains of Turkey, Iran and northern Iraq’s Kurdistan, the two main arteries flow south providing silt, clay, and all the nutrients necessary for the continual spawning of life.

It is this link that some feel will ultimately unite Iraq, if not from some open desire to become one indivisible nation, than at the very least because of an environmentally driven need—access to water.

“There are two places in Iraq—the high places in the north’s mountains and the southern marshlands—where you are speaking with God,” said Narmeen Othman, a Kurd who spent her youth as a Peshmerga, the Kurdish guerilla organization. As the Minister of Iraq’s newly formed Ministry of Environment, oversight of both projects fall to her. “When I was Peshmerga, alone in the mountains, I took my strength from nature, from the grasses and flowers and trees, from the waterfalls and rivers. The same pieces of water that come from our mountains, they end up in the marshes, and they are a gift given to Iraq.”

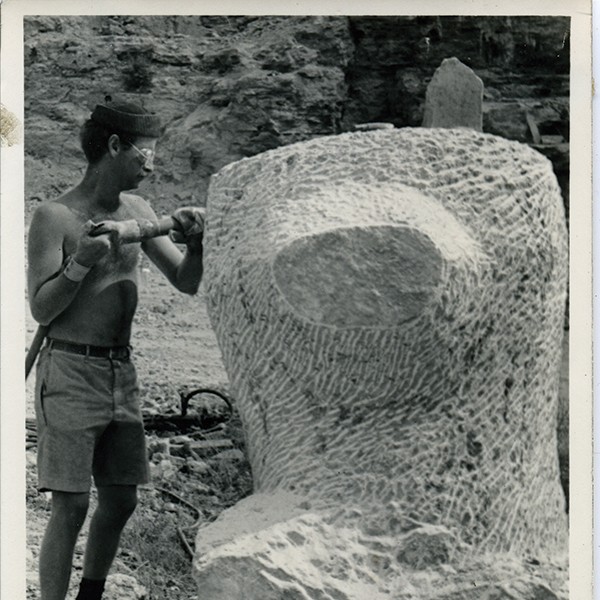

In 2002, soon after reviewing the 2001 United Nations’ Environmental Program report that detailed “one of the world’s greatest environmental disasters”—the decimation of Iraq’s Mesopotamian Marshlands—Azzam Alwash,

an Iraqi expat born in Nassariya, on the fringes of the marshlands, and his American wife, Suzie Alwash, combined knowledge gleaned from their respective PhDs in civil engineering and geology and conceived the Eden Again Project, the forerunner of Nature Iraq. The UN report was not exactly news to Alwash. Despite living in the US, he had kept his thumb on the pulse of his homeland. Yet both he and his wife were horrified by the extent of the devastation. What had been the third largest wetland in the world just 10 years before—8,000 square miles of thriving, expansive, and self-sustaining marshland—had been reduced to just five percent of its original size, purposely destroyed by Saddam Hussein’s regime in the 1990s in retaliation for the Shiite uprising that followed the fi rst US invasion of Iraq in 1991.