Pete Seeger has retired. Or, rather, that's been the plan. But, even at 91, it hasn't quite happened yet.

"Oh, I'd like to. But, well, look over there," he says, pointing to a low couch in the hand-built Beacon home he's shared with his wife, Toshi, and their family for over 60 years. Save for an open sitting spot at the far end, the couch, as well as the coffeetable directly in front of it, are thickly blanketed with sheets of mostly handwritten paper. "Letters," he drones, repeating the word a half dozen more times. "Every day, letters. I don't like to do it this way, but I have to use a form letter now to answer them all. There's just too many to keep up with. A woman comes in once a week to help me with them, Sarah Elisabeth. Her husband's a carpenter, works in the city. A good union man."

All of this—the unwavering sense of responsibility, the commitment to the rights of workers and individuals, and, above all else, the supreme value he places on human beings helping one another—is classic Pete Seeger. He's famously humble about all that he does in their name, but these are the core beliefs that have driven him to work so tirelessly in the areas of social justice and the environment.

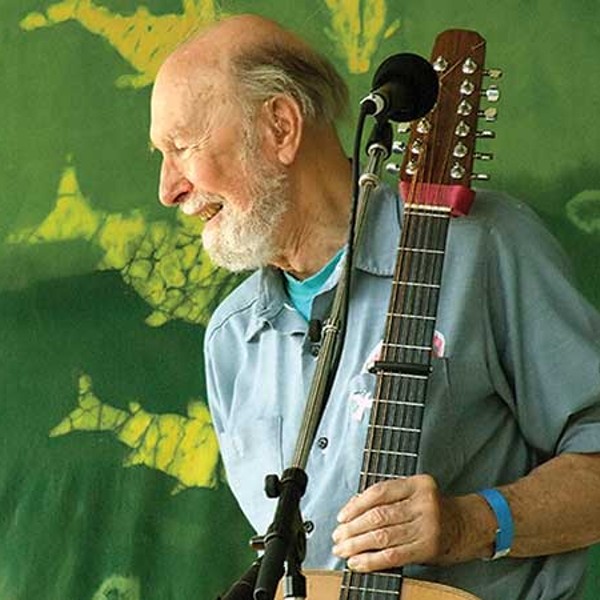

And then, of course, there's his music. Even if you don't know who the man is, or about his devoted activism, odds are you know at least a couple of his tunes. Eternal anthems that sparked the fuses of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary, the Byrds, and basically the entire post-World War II folk revival and protest-song and folk-rock movements: "If I Had a Hammer," "Turn! Turn! Turn!," and "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?" and two he popularized, "We Shall Overcome" and "Little Boxes," to name a few. His adaptations of ethnic chestnuts like "Wimoweh" and "Tzena, Tzena, Tzena" helped forge the world-music scene. And though his voice is now frail with age, Seeger, today sitting in a chair between his two wall-hanging banjos famously inscribed "This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender," keeps right on singing. Eyes closed, he croons from deep memory the lines to old-time nuggets like "It Ain't Gonna Rain No More," the first song he ever learned.

"The clarity of the message in Pete Seeger's songs has always struck me," says Crooked Still banjoist Gregory Liszt, who toured with Bruce Springsteen for his 2006 homage, We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions (Columbia Records). "All of his music is dedicated to deepening the connections between people, even if that theme is not explicitly mentioned in every song. Even in foreign countries where people hardly spoke any English, Pete's songs really got the crowd involved. Good music is always better if it really stands for something."

Seeger was born in the Putnam County town of Patterson in 1919 to ex-Julliard faculty members Charles and Constance Seeger, whose embrace of both music and political activism helped to shape their son early on. Charles, a noted musicologist and composer, served as a professor at the University of California at Berkeley until 1918, by which time his outspoken pacifism had made him somewhat of a pariah. Constance, a violinist and music teacher, encouraged Pete's interest in music by "leaving instruments—fiddles, squeezeboxes, marimbas—lying around the house for me to fool around with."

While young, Seeger discovered author and Boy Scouts of America founder Ernest Thompson Seton. "[Seton] boosted the idea of learning about the North American Indians," he explains. "I learned that they shared everything they had. There was no such thing as one person in the tribe going hungry and the others having full bellies. That seemed to me to be a sensible way to live. Anthropologists call that tribal communism. So I say that I've been a communist ever since I was seven, when I first started reading Seton." It was also when Seeger was seven that his parents divorced, his father remarrying to modernist composer Ruth Crawford and later taking a job as an adviser with Franklin D. Roosevelt's Farm Resettlement program. While traveling with his dad in 1936 he attended the Mountain Folk and Dance Festival in Asheville, North Carolina, where he first heard a five-string banjo. Fascinated, he plunged into learning to play it, eventually taking lessons in the clawhammer style from Kentucky master Rufus Crisp.

Seeger earned an academic scholarship to Harvard, where he performed folk songs for his fellow students and joined a wing of the Youth Communist League. These activities, along with a mounting disillusionment with hermetic academia, led to his grades suffering, and by 1938 he'd dropped out and gone on tour with the left-leaning Vagabond Puppeteers troupe. If from here it starts to sound like the mythical perfect storm that begat America's foremost folk icon, well, that's exactly what it is.

Through his father Seeger next got a job working for Library of Congress music archivist Alan Lomax, with whom he cataloged thousands of folk and blues records and traveled the Deep South making field recordings. His further immersion in the music's raw, plainspoken honesty redoubled his already evangelical commitment to it, and he began to perform many of the tunes he came across. Seeger became their vessel, and were it not for him much of America's rich music might, at best, lay a-moldering in the National Archives instead of soaring from the throats of the people. During this time he met and sang with luminaries like Leadbelly (another musical vessel), Josh White, and Aunt Molly Jackson, among others. But the big bang of the American folk renaissance came in 1940 at a migrant workers benefit, when he met a 28-year-old songster from Oklahoma: Woody Guthrie. The cocky Dust Bowl troubadour had an immediate and profound influence on Seeger, and the pair became tight friends, hopping trains and getting to know the heartland firsthand.

Seeger eventually landed in New York, where he co-founded the Almanac Singers, a string-band collective that soon also featured Guthrie. The group specialized in topical and socially progressive songs and frequently performed at union rallies and leftist events. The pacifist Almanacs changed their antiwar tune after Germany turned on Russia and Pearl Harbor was attacked, but disintegrated as the members grew apart and the group drew criticism for its past stance. Seeger did serve, and was stationed in the South Pacific, where he played for other troops. He married Toshi, "without whom the world would not turn nor the sun shine," in 1943.

After the war Seeger and his fellow ex-Almanac Lee Hays formed the Weavers, who became wildly popular via hit readings of folk standards like "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine" and Leadbelly's "Goodnight Irene." But during the Red Scare of the 1950s the radical pasts of its members landed the group on the government blacklist, which saw them shut out of gigs and record sales. Seeger, who'd long since left the Communist Party, was summoned to stand before the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). When grilled about whether or not he'd performed at Party benefits he refused to answer or plead the Fifth Amendment, asserting that anything he'd done in that vein was protected by the right to free speech. He was convicted for contempt of Congress, a 10-year sentence eventually overturned in 1962, but used the growing backlash against red-baiting to his advantage by performing at colleges, creating the modern touring circuit and becoming the patriarch of the next wave of folk music.

One of the strongest voices of the civil rights movement, Seeger marched and sang freedom songs with Martin Luther King and played countless concerts for the cause. In that decade and into the next he railed against the Vietnam War, performing at peace rallies and even sheltering the odd draft dodger. One of these runaways was musician Victorio Roland Mousaa, who is currently organizing a New York concert for March starring Seeger, Joan Baez, Richie Havens, and others to aid Native American activist Leonard Peltier, who has been imprisoned since 1977 on highly contested murder charges.

Seeger learned to sail while working a job on Cape Cod, and in the mid 1960s bought a small boat that he'd take out on the Hudson. What he saw there—miles of toxic residue, oil pollution, raw sewage—was heartbreaking for the lifelong outdoorsman. "I thought of [economist] John Kenneth Galbraith's great phrase, 'private affluence, public squalor,'" he recalls. "I had enough money to buy this boat, but I was sailing through shit." Resolved to do something about the deplorable state of the once proud, life-giving artery, he co-founded the Clearwater Foundation in 1969 and helped build the sailing sloop and environmental-awareness classroom Clearwater. Over 40 years later, the organization, which the singer calls his greatest achievement, has inspired dozens of kindred efforts worldwide and continues to keep the river clean via fundraising events culminating with June's annual Great Hudson River Revival.

Backed by a school chorus, Seeger and Springsteen sang Guthrie's "This Land is Your Land" at President Obama's inauguration. Two years on, how does Seeger view the administration? He thinks a few seconds. "Compromise is part of life," he says. "But there's a slight difference between compromise and selling out." The recipient of such awards as the National Medal of the Arts and a Kennedy Center Lifetime Achievement Honor, Seeger was recently nominated for his fourth Grammy for last year's Tomorrow's Children (Appleseed Records), a collaboration with Beacon youth chorus the Riverfront Kids. "The kids love listening to his stories, asking him about what his songs mean," says Tery Udell, a fourth-grade teacher at J. V. Forrestal Elementary School, whose students co-founded the group in 2009. "He makes them feel so empowered, like they really can change the world one song at a time."

Seeger's propensity for history is legendary, and it's impossible not to be swept up by the animated way he reels off the accounts of local settlers and the ancients. His eyes light up when talk turns to chopping wood ("I love to go whack!") and about how humanity will be preserved through music, as well as the two other communal arts he says most bring people together: cooking and sports. When he cites humor as another saving grace, the words of one of his heroes, musician and unionist Joe Hill, come to mind: "If a person can put a few common-sense facts into a song and dress them up in a cloak of humor, he will succeed in reaching a great number of workers who are too unintelligent or too indifferent to read."

"If the human race is still here in 100 years, it will be because of lots of people doing lots of little things," Seeger says. "Bigger things can get co-opted or bought off by the powers that be. But if there are many, many little things going on it will be too hard for them to keep up with all of them." What would he call his role in history? "A sower of seeds," he says, referencing one of the Bible's parables. "Some seeds fall on stones and don't even sprout, but some seeds fall on fallow ground and multiply a hundredfold."

Pete and Peggy Seeger will perform a benefit concert for the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild at the Kleinert/James Art Center in Woodstock on March 19. www.woodstockguild.org.