Examples of street art by Unit, Dwell and Mr. Prvrt: A portrait on the back of a delivery van, stenciled commentary over a Banana Republic ad, and a decorated wall.

They wait for a train to pass and then climb up on the railroad bed, trying to stay out of the headlights of passing cars. The wallpaper paste is in a nondescript file box, the spray paint in a camera case. The tall weeds alongside the tracks sparkle with fireflies, and the only sounds are crickets, the occasional passing car, and the crunch of gravel as they trudge forward. They get to a yard, well known among aerosol artists in Albany—the highway overpass that connects Henry Johnson Boulevard to Route 90. The crew sets up shop at the base of the cement pillars, the sounds of the traffic high overhead. They put up three urinal posters on each of the pillars, using a broom-size brush to secure them to the cement. They work methodically, lining up the tops and bottoms of the posters, and smoothing out the wrinkles. When they are finished, they take out black spray paint and sign their names: “Unit” and “Dwell.”

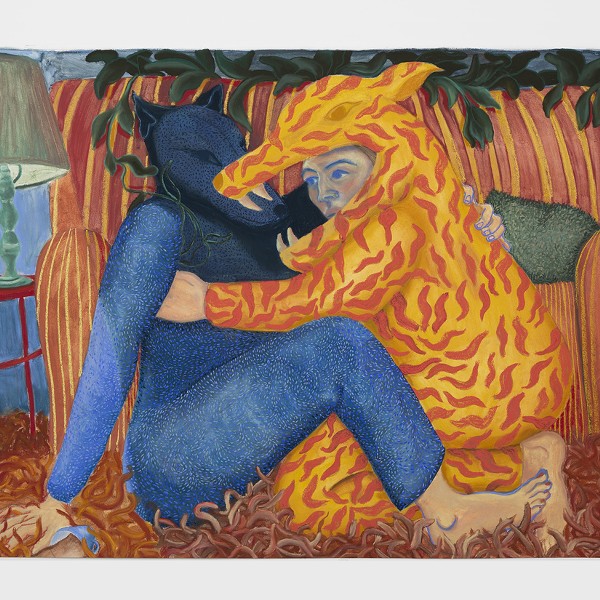

They are street artists, whose illicit artwork graces buildings, billboards, and street signs across the region. They intentionally paint on private property, and in so doing, challenge the concept of public art. Their posters and large, stencil-based drawings give citizens an alternative to the billboards, street signs, and old buildings that dominate everyday life. Their art—which ranges from large-scale portraits to witty caricatures to pointed or whimsical drawings—has the power to startle and delight. Their work gives those who see it a new view of their surroundings, a bit of visual amusement, and a break from conformity.

The pair closely guards their anonymity, refusing to connect their street identities to their real names. Since street art is regarded as vandalism by authorities, their activity is both subversive and risky. While most artists are looking to escape obscurity, Unit and Dwell seek to remain underground. Their aliases are central to their work, Dwell believes, because “the only way my message is going to get across is illegally.”

How long that anonymity will remain is hard to say, as Unit and Dwell deal with growing interest in their work by people in and around the art world, and increasing opportunities for mainstream acclaim. Their most recent lawful opportunity has come in the form of a mural on the wall of the Spectrum 8 Theatre in Albany. It’s the largest project they’ve ever tackled, 25 by 100 feet, and they’re planning on covering the wall with what they’re calling a “post-futuristic freak show.” Dwell and Unit will work with a third partner, Mr. Prvrt. August.

The mural is scheduled to be completed in August, and in early June, Unit and Dwell were doing test runs with their stencils and automotive spray paint. They make the stencils by downloading pictures and Photoshopping them to create color separations. They use the separations in layers, the way printers register color plates, spray-painting one on top of the other. Often their work appears on stickers, posters, and panels they post around the area. Sometimes, as with the Spectrum mural, they paint directly on the walls.

The three artists, who are in their 20s and early-30s, have been working together since 2006. Before they met, they had seen each other’s handiwork on the streets. “They thought I was, like, 10 people,” Mr. Prvrt recalls, “and I thought they were five.”

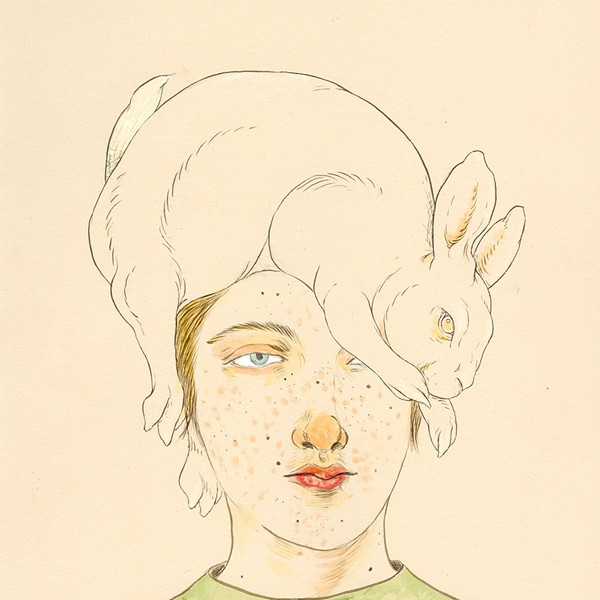

Mr. Prvrt has the most formal training of the group, in illustration and printmaking, and the most experience exhibiting in legitimate settings. From the beginning, however, he also chose to put his work up anonymously around town, first his prints, and, once he began cutting stencils, his stickers and posters. “I didn’t want to have to wait for a show to have my work out there,” he says. He exhibited under both his real name and his street name for a while, but then moved primarily to “Prvrt.”

“When I wanted to show under my real name, I had to think, ‘What the hell do I have that I haven’t put up on the street?’ Eventually, the answer was, ‘Nothing.’”

Unit was an art student at a local college, but dropped out because the environment was too structured. Artificial boundaries and rules were being applied where they didn’t belong, she said. She worked with collage, and began to notice the work of Stain and Scout, local stencil artists. She saw a lot of similarities between collage and stencil, and admired the do-it-yourself approach to art. She cut her first stencil a few years ago, and, unwilling to wait for more formal invitations to exhibit, took to the streets.

Dwell came to street art by way of social activism. Some years ago, he attended a political rally in New York where he and many others were arrested. The protestors were held overnight, and in some cases mistreated, before they were ultimately released. The next day, he said, the rally was front-page news everywhere except the American media. The event was pivotal for him, and made him realize he needed to take a different tack to make sure he was heard.

The group’s work contains a strong element of social rebellion, but it’s more than simply anti-authority. They say their methods are a conscious investigation of the role of art in our society and its potential to transform thinking. The crew, a term for a group of spray-paint artists that work together, makes a distinction between the work that its members do—enhancing the city and shielding citizens from the onslaught of commercial messages—and the work of graffiti artists or vandals. Vandals damage property and graffiti artists speak mostly to other graffiti artists, Mr. Prvrt says. Street art, he contends, beautifies the city.

Locating the art in unlikely places is a key part of the group’s mission. Imposing their work on a billboard, a building, or a tractor-trailer forces public interaction. “I like people to see something beautiful and then have to struggle with themselves because it’s not supposed to be there, because it’s ‘illegal,’” Unit says, derisively emphasizing the word.

They enjoy the thrill of these “bombing” missions, and the taboo pleasure of entering abandoned buildings and underground passages.

“Pretty much, we’ll try the door at any place and see if we can get in,” Dwell says. “People like us, we don’t ask permission to do things. We just do it until we get caught.”

The artists see themselves as rehabilitating ramshackle spaces with their work, and enjoy just being in them and witnessing their decomposition. They are fascinated by decay, and describe in great detail the peculiar beauty of watching ancient structures fold under the weight of time. The group incorporates materials from the buildings they hit, using pieces of derelict metal and wood as canvases. The recycled materials provide interesting work surfaces, Unit explains, showing off a container lid with a flower painted in the center, but otherwise caked with rust and scratches. She likes the fact their work compels others to see such surfaces as beautiful in and of themselves, maybe even before examining the artwork.

If old buildings appeal to the artists’ aesthetic side, their political intention is on display in other public spaces. The crew members put work on street signs, utility boxes, and storefronts. They like to take control of billboards and advertisements, purposefully painting over ads in an attempt to subvert their messages, and openly challenge corporate dominion of public space. Corporations, Dwell maintains, use all available surfaces to plug their products and make money. The crew’s art—particularly the urinal paste-ups they do— is a way to smash these ads and reclaim public space. “Basically saying, ‘Piss on advertising,’” Dwell says.

Making art isn’t just about pretty pictures, Mr. Prvrt says. At the beginning of his art career, Mr. Prvrt consciously sought negative attention, believing that distaste for his work was a stronger response than admiration. “Long before I started making things I thought people would like, I tried to make things people wouldn’t like,” he says.

He chose the moniker Prvrt because it was an easy way to get attention and challenge people’s perceptions. He could create interesting juxtapositions simply by paring his name with incongruous images—a praying priest, a young woman. He started creating images that were more complex and aesthetically pleasing when he came to understand they were more likely to be preserved. He said he added the prefix “Mr.” to show he’d grown as an artist.

But even beautiful images get washed off, sanded out, or painted over. The group has put up pieces one night, and come back the next day to document the work only to find the piece torn down.

In late 2006, they put up an image of a woman in silhouette, her hair laced with flowers, on an abandoned building on Delaware Avenue and Whitehall Road in Albany. Perry Woodin, who was active in the area’s Neighborhood Watch program, said the organization’s listserv buzzed with positive responses to the piece. Then a rumor reached him that the City of Albany was going to remove the work. Afraid the artwork would be destroyed, Perry took it down and held it for safekeeping. He plans to open a gallery on Delaware Avenue next year and, with the crew’s blessing, will install it as part of the gallery’s permanent collection.

The incident highlights conflicting perceptions of the crew’s work. “[The city] called it graffiti,” Perry said. “Nobody in the neighborhood would have called it graffiti.”

The line between graffiti and street art remains a blurred one. Both appear on the street and both use the same medium, spray paint. But Dwell, who admires graffiti, says that though the two aesthetics share some commonalities, graffiti is a distinctly different skill with a different set of rules.

Graffiti is primarily names and writing, and was coined from the Italian word graffito, used to describe the inscriptions on early Roman walls. Graffiti evolved into a way gangs marked their territory, but, according to Dwell, the current graffiti scene has little to do with gangs. “Gang graffiti went out a long time ago,” he says. “It’s more like people have a name and they want to see it as many places as possible. It’s like a game.” Graffiti artists also challenge one another, matching their skills against others in ongoing, anonymous competitions. They vie for space in “yards,” or areas of high concentrations of work, hoping to put up pieces that will be admired and preserved by other artists. If people like it, other artists will let it stay, but if they don’t, it will get painted over.

In contrast, artists like Dwell, Unit, and Mr. Prvrt rely on images more than words to convey their message. Graffiti is often made on the spur of the moment, whereas street artists spend hours preparing their intricate stencil pictures before going out on what they call “an installation.” Their art has opened doors to galleries and other venues, including Albany Underground Artists, Albany International Airport, the Kismet Gallery and, most recently, the Spectrum. In August 2006, Albany Center Gallery hosted the crew’s “Playful Maidens of the Spray” exhibit. Executive Director Sarah Martinez invited them to do a show after she saw their work on Delaware Avenue and at local art events.

“The mission of the gallery is to bring art to the public, and in my opinion, with their street art, nobody does it better,” Martinez said. The highly attended “Maidens” show ran for six weeks, and was the gallery’s most successful show in terms of both sales and attention, she says.

The tension between working inside the establishment and outside the law—what Martinez calls “the light and dark sides of their work”—is a critical element of the crew’s success. Art should create this tension, Martinez says.

“Look at the history of art—artists have always played devil’s advocate,” Martinez says. “Yes, what they’re doing is illegal, and there are some morals involved, but if you look at the broader picture, they’re saying something important.”

The group has an ambivalent relationship with the gallery scene. Its members see the two settings working together, but disagree on the cause and effect—whether the gallery shows keep the street art moving or the street art makes the gallery shows happen. The main goal for all three is to make a living off their art, and they realize that selling their work or being hired to do projects is a way to do that. The question is, at what cost? Ideally, they would make enough money so that they could afford to be choosy about their projects. “That’s ultimately the way to go,” says Unit, “to get paid for your art, and not compromise too much.”

All three artists are committed to continuing on the street, even if it means risking arrest, which they accept as an eventual certainty. “It’s a numbers game,” Dwell said. “We’re going to get caught at some point.”

When they do get caught, they say, they’ll have no regrets, because their mission is noble and their work valuable.

“You have to know what you’re doing is not wrong,” Dwell said. “You have to feel like you have the right to be there.”

OPPOSITE: wearing masks to protect their identities, Mr. Prvrt, Unit and Dwell in their studio.

above: Urinals stenciled on a bridge support

OPPOSITE: The tools of the trade, including a stencil, spray paint, and safety mask.

above: Unit, Mr. Prvrt, and Dwell with a large portrait head they created. The graffiti was left by other artists.