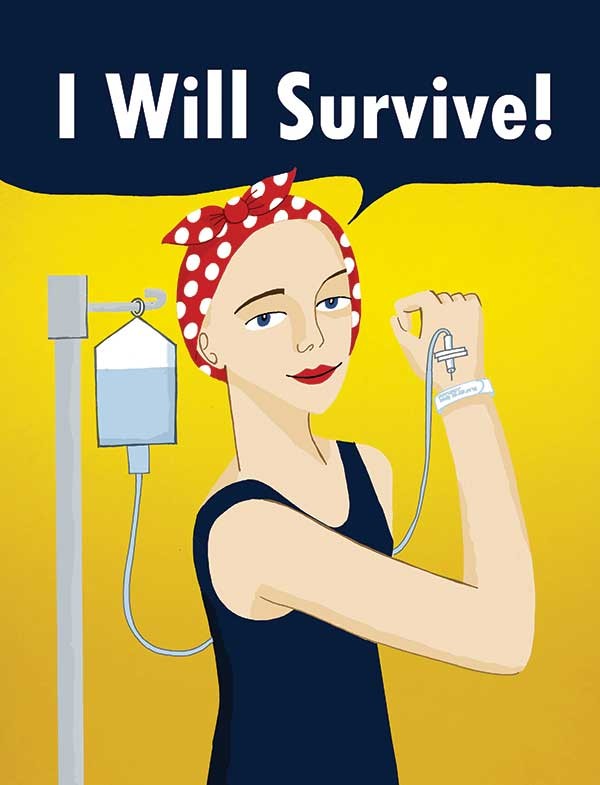

Louise Kuklis is still here—in fact, she just got back from seeing the manatees swim in the waters of Florida. And that is a miracle, because for the past eight years Kuklis has journeyed through Stage III and IV colon cancer to her present, and very blessed, state of remission. Some days, she was merely surviving the pain, nausea, and countless bring-me-to-my-knees indignities that cancer brings. After the Stage IV diagnosis, forced to retire from the teaching job she loved, "I was basically numb for the first month or two, but got my footing and sort of went into survival mode," she says. Despite it all, Kuklis was, and still is, really living—dancing at her son's wedding after her first six-month round of chemotherapy, holding her newborn grandchild after the cancer metastasized, then stabilized, in her lungs. At White Plains Hospital, where the oncology nurses know her entire family by name, Kuklis learned that she could knit and paint during the chemo infusions that she would endure over the years. She wrote down her experiences in the hospital's Narrative Medicine program (a reading and writing group for cancer patients and caregivers), and went on to see two of her paintings published in a book and one on display in Manhattan's Grand Central Terminal. As if to put a cherry on top of her unstoppable spirit, she completed two triathlons with the Rye YMCA's Livestrong program.

Waltzing through cancer, and thriving over pain and suffering, is something Kuklis had seen her mother do before succumbing to the illness at 78—so in some ways, she felt groomed for it. "My mother left me this legacy of 'Live your life and treat the cancer, but don't let it become the focus of your life,'" says Kuklis. Never before has advice like this rung so true, and for so many people. According to a 2014 report from the American Cancer Society, the number of cancer survivors is growing; we have an estimated 14.5 million cancer survivors in the United States today, and that figure is expected to spike to 19 million by 2024. Cancer is still a top killer (it's the second-leading cause of death in the US, just after heart disease), but for fortunate people on a case-by-case basis, its stranglehold is loosening. Chastening these statistics is cancer's well-known ability to come back, sometimes in a new place in the body or in a newly aggressive form, like a B-movie horror villain.

Cancer As a Chronic Illness

It may seem a bold, even risky statement to say that cancer today is becoming less of a death sentence and more of a chronic illness that can be managed with vigilance and care. (Plenty of people caught in the final fire of disease, and their loved ones, would disagree.) Yet doctors and researchers in the oncology world see this happening for certain people and types of cancers—especially breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer, among others—thanks to an arsenal of very limber and precise modern medical treatments. "People think 'cancer' and they think 'death,' but that in fact is incorrect," says Una Hopkins, PhD, administrative director of the Dickstein Cancer Center at White Plains Hospital. "We've advanced so far in our ability to personalize treatments to the particular cancer that an individual has. When we individualize treatment plans, we put the illness into a chronic state, as we would with hypertension or diabetes, or HIV for that matter. We find the right way to sequence the drugs or radiation, or whatever has to happen for that very specific cancer. Sometimes it's one year, two years, even five years, that we keep that person going along their lines of recovery."

Not just one, but several reasons point to why people are living longer with cancer. "For many kinds of cancer, there are now second, third, and even fourth lines of treatment for people if something isn't working. That's a huge advance," says Sandi Cassese, vice president of oncology services at Health Quest, which includes three hospitals—Vassar Brothers Medical Center in Poughkeepsie, Northern Dutchess Hospital in Rhinebeck, and Putnam Hospital Center in Carmel. If one chemotherapy doesn't work, a patient might have several more to try; after that, a drug that's in trial is often available to extend the options. Game-changing medications like Herceptin and Tamoxifen for breast cancer are also adding to the number of cancer survivors; Cassese calls them "super wonder drugs." And the genetic testing of tumors—a burgeoning field with enormous potential in the fight against cancer—is fine-tuning doctors' ability to offer targeted therapies and specific chemotherapies for the best outcome.

From Stage IV to Cancer Free

Pam Brown—chef-owner of Garden Café on the Green, Woodstock's much-loved vegan restaurant—had always prided herself on exercising every day, doing yoga, and eating vegan since 1967 ("I was a raging hippie," she says). So Brown was shocked when, in October 2013, she was diagnosed with Stage IV, very metastasized ovarian cancer. "I'd been living the ideal healthy lifestyle, except for the extreme amount of work and stress, which is definitely a factor in this," says Brown. Her surgeon said the tumor was like a bag of peas that had burst open and spread everywhere, all the way up to her lungs. "They said, 'Here's what's going to happen—you're going to have a complete hysterectomy, you're going to go through chemotherapy, lose your hair, the whole deal.' My attitude was 'Let's just get this all done.' There's more pain in resisting things than in accepting what's going on."

Naturally petite and energetic, Brown was a wasted 78 pounds when she went into surgery (about 20 pounds below her normal weight). She spent the next six months at home, going to St. Peter's Hospital in Albany for chemo every week for 18 weeks. Her doctor told her to eat meat because her tumor-ravaged body needed protein. Instead, she says, "I ate eggs, dairy, and fish—none of which I enjoyed—but I was grateful to the animals. I'd thank them as I'd eat it." Brown tried alternative therapies like cannabis oil and herbs ("I figured it couldn't hurt") and forced herself out of bed to walk the treadmill. A parade of "amazing people" came to her house with food; to help with her medical expenses, a friend started a Gofundme site that raised $25,000 from her community in four days.

Today Brown is cancer free, but she understands that it could come back at any time. ("They don't declare remission. I get a blood test every month.") She has her battle scars—painful nerve damage, fingernails that fell off, dental issues from the chemo. Back to her vegan diet and back to work (though working a little bit less), she's convinced that a foundation of good health contributed to her recovery. "Sometimes I think, oh my God, I had cancer but I'm still here. I'm amazed and blessed that I'm here."

Postcancer: A Survival Guide

Like Kuklis, Brown is entering a different stage of cancer called survivorship—a relatively new term that's used mainly to describe the post-treatment phase. New regulation requires all patients ending their cancer treatment because they've been "cured" to have a survivorship plan. Developed with their doctor, these are living plans that include a patient's diagnosis and treatment history as well as a complete blueprint for care going forward—recommended screenings, physical therapy, nutritional therapy, and the like. Perhaps the most profound change in oncology today is a movement to apply the principles of survivorship to the entire journey of cancer care. Says Cassese, "In the old days, when people spoke to patients of palliative care, it was the equivalent of hospice. There's growing enthusiasm around changing the name [palliative care] to survivorship care, focusing on treating the whole person and relieving all symptoms, be they pain, stress, fatigue, insomnia. It's all about quality of life."

Meanwhile, Health Quest is working on bolstering its cancer rehab through a program called STAR, or "survivorship training and rehabilitation"; about 50 health-care providers are undergoing the training. "As cancer is becoming a chronic problem that people can live with, it's really critical to look at how we treat these patients," says thoracic surgeon Cliff Connery, MD, FAC, medical director of the Dyson Center for Cancer Care at Vassar Brothers Hospital, and Health Quest's director of thoracic oncology and surgery. "How much do we beat them up when we're trying to cure the cancer? What sort of side effects do they have?" Connery works mainly with lung cancer patients, who typically have a lower chance of survival—though with newly recommended low-dose CT scan screenings for those at high risk for lung cancer, this prognosis may be changing. (Stay tuned for next month's article on the evolving world of lung cancer care.)

Keeping the C-Word at Bay

For people looking to survive cancer by never getting it in the first place, the obvious adages ring true. Don't smoke. Eat your vegetables. Exercise. Keep your weight in the normal range (obesity is a cancer risk factor). And at physical exams, be your own best advocate by talking to your doctor about screenings. Regular mammograms, colonoscopies, and the like, administered at the recommended times, can catch cancer earlier and dramatically increase chances of survival. Those with a family history and other high-risk individuals need to be extra vigilant. "Every day I talk to someone who skipped an exam—by three months, six months, a year—and got bad news," says Cassese. "There's no way to get that back. We want to catch it as soon as we humanly can. If someone can catch a lung cancer early enough that it can be treated with surgery, it makes all the difference in their survival."

Kuklis, for one, will not miss the regular CT scan screenings that her doctors have laid out on a time line to detect any recurrence of disease. The only thing separating her from a "normal" life is one 30-minute infusion each month of the biological agent Avastin, which her doctors recommend she keeps taking. What got her through? Family and friends. Exercise. Good health insurance. Meanwhile, her "cancer home" at White Plains Hospital's Dickstein Cancer Center is growing, with a new building to be unveiled in October and integrative therapies hardwired into the program with acupuncture, Reiki, aromatherapy, and more. Some of these are woven into Kuklis's lifestyle now—"I do yoga, walk, and meditate each day," she says.

For Pam Brown, "It was a little embarrassing to be a vegan and get cancer," she says with a self-deprecating smile. "I no longer feel invincible." But Brown will be 70 in June and is living proof that, as she says, "There's always hope. No matter what they tell you."

This is the first of two articles about cancer. The next article, about advances in lung cancer treatment, will appear in the April issue.

RESOURCES

Clifford Connery, MD, FAC (845) 483-6920