On a bright morning, under an attractive layer of fresh snow, the rolling mountains of southern Berkshire County seem to heave a deep sigh of satisfaction as they welcome yet another season of looking better then where you’re from.

Just two hours from New York City and Boston, and a short jaunt east from the Hudson Valley, the Berkshires are anything but a shallow beauty. The area, it should almost go without saying, is widely renowned as a world-class destination for culture and the arts. The summer months are undoubtedly the busiest in the Berkshire towns of Great Barrington, Stockbridge, and Lenox. Many antique shops and galleries close or run limited hours until the snow melts, but with the aid of nearby ski resorts like Butternut and Catamount, and the draw of museums, there’s still plenty of life here in the winter.

Great Barrington

“My wife and I consider Great Barrington the prettiest and nicest place we’ve ever been,” says Alan Chartock, President and CEO of WAMC/Northeast Public Radio, a Great Barrington resident for nearly 40 years. Chartock breaks his town down as succinctly as perhaps only a news-radio man can. “It has all the great stuff. It’s got magnificent ski areas, hiking; it’s got an environmental ethos; and it has a community of really beautiful people.” Chartock says Great Barrington has changed a lot over the years and has a “more comprehensive” population then ever before. He feels the growing diversity is a good thing for the artistic-minded town and the Berkshires at large.

This year, Great Barrington will also be celebrate its 250th anniversary, with a series of monthly events ranging from concerts and antique-auto shows to a soapbox derby and a beard-growing competition. “It’s the commercial, cultural hub of the south county,” City Manager Kevin O’Donnell says, adding that the town has weathered the recession better than most. “We’ve got the best shopping and 45 restaurants. Business is undoubtedly off, but people are still coming to town.”

One of Great Barrington’s more eclectic shopping experiences, just outside of the town center on Route 7, is easy to spot, given the eight-foot Buddha head beside the entrance. Asia Barong is an expansive emporium offering all manner of art pieces, furniture, antiques, and even structures like a stilted rice house from Thailand. The massive collection of objects handpicked from their native lands by owner William Talbot are housed in a space large enough to be a lumberyard.

Talbot says that while a large chunk of his business is providing pieces to temples, museums, and nightclubs, being located in Great Barrington is mutually beneficial for his business and the town. “It’s an artistic area and the local community is pretty sophisticated,” he says, adding that people often come to the area to see things in his shop that they can’t find anywhere else.

Great Barrington has a productive mix of working artists and patrons that allows for there to be interest in a wide range of artistic styles, according to Talbot. “I believe it all goes hand in hand,” he says. “There’s also a tremendous amount of innovation here.”

One of the organizations bringing people into Great Barrington is the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center, housed in the 105-year-old Mahaiwe movie theater on Castle Street. The historic landmark underwent a $7 million renovation to restore its original appearance and acoustics that was completed in 2006. Given the august legacy of so many of the Berkshires’ performance venues, like Tanglewood and Jacob’s Pillow, the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center is in its infancy as it begins its seventh season, but its presence is already being felt throughout town. Restaurants like the highly regarded Castle Street Cafe next door now offer specials on nights when the Mahaiwe has a large draw.

Mahaiwe Executive Director Beryl Jolly says Great Barrington has really embraced the theater and business has bounced back from a hard hit in 2009 when the whole region suffered. “There’s something to do almost every weekend of the year now,” Jolly says, “We’re offering something that brings in all aspects of the community, from people from New York and Boston to [students on] school field trips.”

Between concerts and live theater and workshops the Mahaiwe shows classic movies and live high-definition broadcasts of the Metropolitan Opera. Jolly says the Center is particularly looking forward to February 18, when it will host a Rennie Harris PureMovement Hip-Hop dance workshop and performance, and March 5, when the Flying Karamazov Brothers will bring their unique comedic juggling act to the theater. “I think we complement [Great Barrington],” Jolly says, “and offer something special that [extends] it to everyone.”

Stockbridge

It’s easy to walk into the Norman Rockwell Museum with a lot of baggage. I did. I was prepared to marvel at the skill of his brush and the meticulousness of his near -photo-realistic illustration, but I was also prepared to remain unmoved by images seen innumerable times before.

I wasn’t faulting Rockwell for my lack of enthusiasm. I figured that he was simply a victim of his own success in a nation saturated by his utopian icons. How could Rockwell’s paintings still hold relevance in modern times, in a world rabidly ripping apart any remaining scraps of the societal fabric his works are draped in?

One of the joys of art is being surprised by the range and power of emotions a piece pulls from rarely traveled internal places. That image of a boy with a bindlestiff elbowed up at a soda fountain beside a smiling cop isn’t supposed to connect anymore. But then, standing before the full-scale painting of The Runaway inside the impeccably curated gallery your mind begins to wander down where you thought it wouldn’t and you find important questions. What would that painting look like today? What would that painting look like painted then but if the boy was black? What would so many of Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers have looked like had the editors allowed him to paint African Americans in anything but a service position?

“He created a world that was a slice of what he wished life would be like,” Jeremy Clowe, manager of media services at the Norman Rockwell Museum, says. “Some of the settings have changed but the themes are the same. It may not look like this anymore but it’s still the same sensation.” Clowe says The Runaway in particular is still highly regarded by police. It’s important to realize, he pointed out, that basic tropes resonate in a variety of ways for different people.

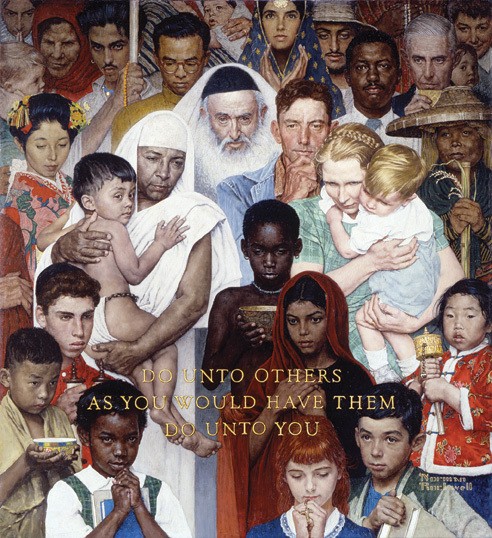

Then you turn around and there’s more. The original Golden Rule sneaks up on you, the weight of that universal desire for tolerance on one canvas. In the galleries’ center room, Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” series encircles the viewer and immediately drives home the pregnancy of the painter’s idealism. “People are particularly moved by the Four Freedoms. I think in difficult times the museum is sort of like a balm,” Clowe says, adding that the accessibility of Rockwell’s style allows everyone, no matter their artistic literacy, to take something away from the paintings. “There’s not a lot of pretense. You don’t feel like you have to ‘get it.’”

The museum also showcases work from modern illustrators to highlight the work of artists walking in, or at least near, Rockwell’s footsteps. The current exhibition of illustrations by Jerry Pinkney includes moving historical scenes of the African American experience and provides a thought provoking addition to the main galleries. Pinkney recently won the Caldecott Medal for his reimagined version of the children’s book The Lion and the Mouse and in December celebrated his birthday at the museum.

The museum has also sent out traveling exhibitions, including “Norman Rockwell Behind the Camera,” a deep look into the artist’s process, working off of photographs of models, some of whom still reside in Stockbridge. It was easy for me to confuse Rockwell’s timelessness for cliche. Standing before his works it was even easier to realize I was wrong.

Stockbridge earned the descriptive additive “Rockwellian” when it’s quaint main street was painted by its most famous resident. Large New England mansions line the road and the business district is warmly understated. There’s the Main Street Cafe, with a chatty young waitress who knows everyone’s name and sticks a candy cane in hot cocoas, an unattended general store where one is apparently on the honor system to go into the cafe to pay for their purchase, and then at the end of the street rests the palatial Red Lion Inn.

“There’s been an inn here with a red lion in front since 1773,” says Carol Bosco Baumann, Red Lion director of marketing and communication, sitting in the inn’s crowded lobby beside an immodest Christmas tree. The gentle sound of a harp strummed live by the fireplace bounces off the antique lined walls. “It started as a Tavern and as in any traditional New England town, it was a gathering place,” Baumann says.

While the atmosphere of the inn is historically authentic, there are undeniable undercurrents of modernity in their philosophy. Environmentally conscious renovations to the inn’s infrastructure, for instance, garnered the inn an award from the American Hotel and Lodging Association. “People say [the inn] is like a postcard,” Baumann says, “and yes, we are, but we also take a lot of pride in doing things differently, in going energy efficient, in supporting the local economy.”

The Red Lion doesn’t shy away from giving credit to, or bragging about, their award-winning executive chef, Brian J. Alberg. The chef has grabbed attention for his locally sourced menus; Alberg even raises his own pigs for the restaurant. On February 4, Alberg will return to the James Beard Foundation in New York City to lead a team of regional chefs in a Berkshire-Raised Whole-Hog event, demonstrating how to use the entirety of a pig, with a menu ranging from Smoked Tomato and Bacon Bloody Marys to 48-Hour Sous Vide Carolina Barbecue–Style Spareribs with Mustard Kimchi and Pig Tail Torchon.

Once again, Stockbridge surprises. What appears calm and familiar on the surface is actually a well-crafted front supported by a much deeper consciousness.

Lenox

Tanglewood is the largest draw in Lenox and one of the best-known institutions in the Berkshires. Tanglewood has been a part of the Berkshire experience since 1934, when summering patrons got together to bring the New York Philharmonic to perform three outdoor concerts. The Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) was added the following year. Classical performances have echoed from the stage, and the tent before it, every year since, minus three during World War II. The schedule for the 2011 season includes four performances by Yo-Yo Ma, and performances by the Mark Morris Dance Troupe and James Taylor, in addition to the BSO’s annual concert series.

While Lenox businesses can flourish in the fat times of summer, winter in town is unavoidably quiet, with slight improvements on the weekends. Most galleries are closed now, or are open by appointment only. Two sculptors, at opposite ends of the artistic spectrum, use the winter to create work in Lenox. Andrew DeVries and Tom Fiorini, in spite of the rivalry that they both say can exist in the town among its numerous local artists, have become good friends. Both believe that having a town filled with art makes getting their pieces seen much easier and creates an artistic dialog that’s unique to the region.

Fierini welds together found metal objects to create what he calls “junk sculptures.” He believes people either like his work or they don’t. A lot do. “People say it’s an insult to call it junk,” Fiorini avers, sitting in a chair he made out of iron and road signs that’s almost too heavy to pull out from behind his dining room table. “I don’t think it is. I think it’s less snobby and pretentious.”

Fiorini has lived in the Lenox area his whole life and figures he’s the only artist in town that’s actually from it. “It’s kind of funny we grew up here hating New Yorkers; now they’re a lot of my customers,” he says. Fierini doesn’t go many places besides his studio and his apartment but says Lenox has been good to him. In an outdoor gallery off Church Street a number of his pieces are on display: dogs, horses, an iron cowboy.

Across the street from Fiorini’s sculpture garden is Devries’ gallery, closed for the winter. “The Berkshires lend themselves to individuality and the ability and necessity to be creative,” says DeVries, who is best known for his large, realistic figural bronze sculptures, which manage to capture both the movement and delicate balance of dance in a decidedly firm medium. “I thought about [opening my gallery in] Great Barrington, it’s a beautiful city. But it’s a city. There’s a lot to be said about Lenox. It’s small, but there’s a community here. There’s room for people like Tom [Fierini] to bloom—like me, too.”

DeVries lets out one of his signature explosive laughs that manages to be both infectious and terrifyingly loud at the same time and then becomes introspective again. “Sometimes I feel like there must be a magnet buried in the ground in Berkshire County that’s pulled all these things together,” Devries says wistfully. “It’s powerful, it really is.”

Photo of Stockbridge Bowl by Kevin Sprague, wwww.studiotwo.com.