Spring is not the time to be talking about death. Especially this spring. The apocalyptically record-busting winter that had us quaking in its sadistic, frozen-and-repeatedly-refrozen grip until early April has at last retracted its heartless icicle pincers. This afternoon, Leon Botstein, the president of Bard College, a near caricature of dignity in his ever-present suit and bowtie, is relaxing on the veranda of his stately campus home with a thick cigar and a cup of sugared tea. Outside, the air is fresh, the birds are singing, and the sun is utterly glorious. And yet right now, here we are, talking about death. And music. "Mahler never got to hear it performed; he died before that could happen," says Botstein about Gustav Mahler's (1860-1911) Ninth Symphony, which as the principal conductor and music director of the American Symphony Orchestra, he will stage this month with ASO members and other musicians at the college. The concert is in honor of Bard trustee Murray Liebowitz, who passed last December and left the funding and precise request for the work to be performed at Bard's Fisher Center. " [The work] is about death—just before he wrote it, Mahler had been diagnosed with heart arrhythmia, which was still fatal in the early 20th century—but in this music people also hear a representation of the struggles of life. It has a hard edge, which is disturbing. But it also has a lyrical edge, which is very beautiful." Like life, the Austrian composer's Ninth is a hill-and-dale of emotion, from the tentative, heartbeat-emulating opening movement, through the heights of its animated landler dances and violent dissonance in the two middle movements, through the gut-wrenching, painfully slow final strains of its closing adagio, whose very last, torturously slow notes the creator directed to be played ersterbend ("dying away"). Mahler lost a daughter to scarlet fever and channeled his despair into the writing of the Ninth; after his own daughter died in 1981, Botstein coped with his grief by picking up the baton he'd laid down at the dawn of his illustrious academic career. "The mark of maturity is that we learn to accept our mortality, and yet we persist in our search for immortality," said Leonard Bernstein while lecturing on the Mahler symphony. "We believe." Clearly, the lesson to be learned, both from Mahler's Ninth and spring's rebirth, is that in death there is life.

Botstein's life began in 1946 in Zurich, Switzerland. His parents, both physicians, were Polish-Russian Jews who had fled the Holocaust (his father was the only survivor within his own family; two uncles perished in the Warsaw Ghetto), but were denied citizenship and with it their licenses to practice medicine. So when little Leon, the youngest of three siblings, was two, the multilingual family emigrated to the U.S., settling in a three-room apartment in the Bronx neighborhood of Riverdale. "My parents were very idealistic, money wasn't important to them," Botstein says. "I don't think they ever stepped inside a Fifth Avenue store. We'd take public transportation into Manhattan and walk by Central Park West, and I knew that that was where the rich people lived. But I never felt deprived, and I never envied anyone for being better off financially." He credits his mother with instilling in him her love of music, which led to his studying violin at age nine. When she began going deaf, it only strengthened his resolve to pursue music. "I saw her being deprived of something she really loved, and my first thought was that I needed to work harder on her behalf." Unfortunately, it soon became clear that her young son, who describes himself as "naturally clumsy," wasn't a virtuoso. "I wasn't very good, but I had a really good teacher, Roman Totenberg," the maestro explains. "He helped me see that since I understood theory well I could use that as a basis to play to my strength, and to consider becoming a composer. I liked the idea of being a storyteller, but I wasn't very motivated to write. I was attracted to the idea, though, that, as a conductor, you can make the stories of others come alive."

Although he may not have been a violin prodigy, Botstein certainly was an intellectual one. Upon graduating from the High School of Music and Art at age 16, he enrolled at the University of Chicago to study history and philosophy. While there, he became the concertmaster and assistant conductor of the university's symphonic orchestra and founded its still-extant chamber orchestra. After studying at Tanglewood, he attended graduate school at Harvard, where he served as assistant conductor of the Harvard Radcliffe Orchestra and conducted a group comprised of students and medical professionals. "My parents were 'instinctive patriots' who felt an obligation to 'give back' to their country," Botstein recalls. "That, and the general idealism of the 1960s, made me interested in public service. I won a Sloan Foundation Fellowship in 1969 to work as a special assistant to the president at the New York City Board of Education." Word of his diligence spread, and the following year he was recruited to take over managing Franconia College, an experimental liberal arts institution in northern New Hampshire, making him, at 23 years old, the youngest college president in history. "Franconia was basically a converted old [1882] hotel; some of the students lived in cabins," says Botstein, who while at the school netted grants, constructed dorms and a student union, and established the still-ongoing White Mountain Music Festival nearby. "[The college] was under the protection of Dartmouth, and I had the feeling that some of the trustees thought I'd put the place out of business—'Who's this Boston/New York hippie, and what's he doing up there?' [Laughs.]" Three years after he'd arrived, however, Botstein moved on to the position for which he appears to have been preordained.

He didn't know much about Bard College when he signed on as its new president in 1975. "I knew it was a progressive liberal arts institution, but not much more than that," admits Botstein, whose work at Franconia caught the attention of the Annandale-on-Hudson administrators. Immediately upon his appointment, he set to work on rebuilding the 1860-founded college's curriculum in line with his brazenly pluralist vision, which places the creative and performing arts on equal footing with standard university studies. One of his more radical and most talked-about recent actions has been to attract, alongside Bard's respected conventional accredited professors, well-spoken famous figures from across various artistic disciplines to teach at the college. This includes the poet John Ashbery; the authors Neil Gaiman, Luc Sante, and Chinua Achebe; and the musician and performance artist Amanda Palmer (the latter was profiled in the November 2014 issue of Chronogram). "In some cases public intellectuals make better teachers than so-called 'experts,'" he explains. "Any individual who can actually make what he or she knows interesting and compelling to people has a very strong basis to be a great teacher."

When talking about Bard and music, several moves of Botstein's ongoing reboot spring to mind. The first is the creation of the internationally acclaimed Bard Music Festival. Founded in 1990 and held in August, the two-week affair focuses on a single composer and encompasses concerts interspersed with talks, panel discussions, and other special events and the publication of a book of scholarly writings. This year's festival, titled "Chávez and His World," celebrates Mexican composer Carlos Chávez. The success of the festival set the scene for the construction of the campus's architecturally and acoustically stunning, Frank Gehry-designed Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts. Called "a big risk that's worked out really well, thankfully," by Botstein and "[possibly] the best small concert hall in the United States" by The New Yorker, the breathtaking venue took $62 million in donations and three years to build, opening in 2003. The young president's next brainchild, the six-week, pan-artistic Bard SummerScape festival, was inspired by the advent of the Fisher Center. SummerScape expands on the theme of the overlapping Bard Music Festival's highlighted composer, putting their music in a broader cultural context with opera, dance performances, films, lectures, cabaret, and other events, all relating to the core figure and demonstrating the interconnectedness of art and society. "It's a cornucopia of wonderful things," says composer, conductor, and musicologist Byron Adams, who served as scholar-in-residence for 2007's "Elgar and His World" series. "What Leon and Bard have created with these festivals is absolutely unique, and in many cases they include works that have never been performed in America before."

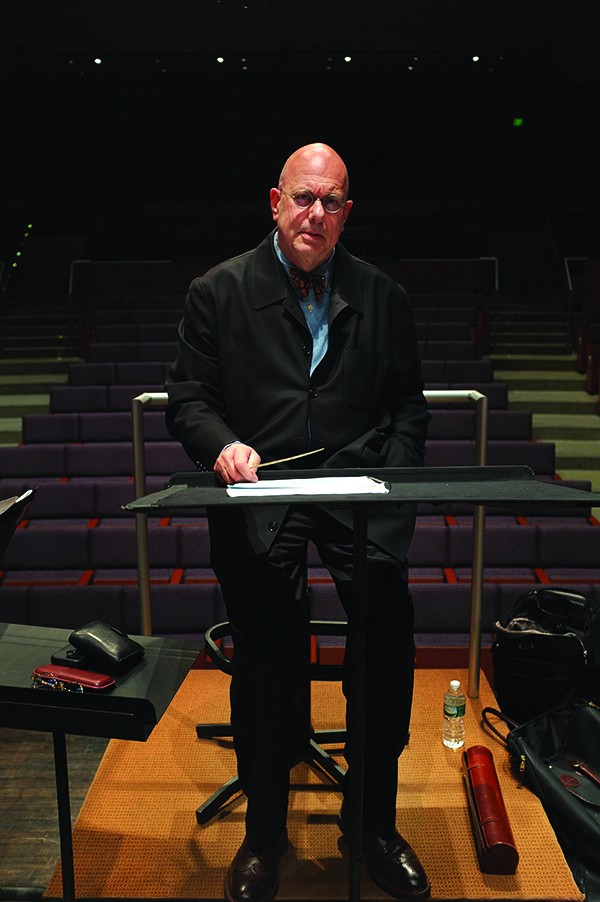

And then there's Botstein the conductor. In 1992, after leading the Hudson Valley Philharmonic, he was selected as the music director and principal conductor the American Symphony Orchestra, an appointment he still holds. The ASO was established in 1962 by conductor Leopold Stokowski with the mission of making orchestral music affordable and accessible to the masses. Since taking over, Botstein, ever the maverick, has honed this undertaking further still by presenting historically ignored works alongside recognized masterpieces in thematically organized programs, to provide greater understanding of the music. "For too long, orchestras have operated on the idea that people only go to see what they know," says Botstein. "[Orchestras] play the same repertoire pieces over and over again. It's like going to an art museum that has 30 rooms full of treasures from 1700 to 2000 and finding out they only have two rooms open to the public. To me, that's a crime against history." Besides heading the ASO, Botstein led the Jerusalem Sympony Orchestra from 2003 to 2011 and currently leads the Bard College Conservatory of Music Orchestra, which regularly tours in the U.S. and abroad. "Working with [Botstein] is very inspiring," says violinist and orchestra member Reina Murooka, a fourth-year German studies major. "The stories he tells about the music we're playing and what was happening at the time it was composed are always amazing."

Over the decades, Botstein has written, in German and English, shelffuls of books, papers, and essays on musicology, history, and education. It's in the latter field that Botstein, as an outspoken academic theoretician, continues to make the boldest waves, lobbying for a national early college system, the abolishment of SATs, and other changes (see his 1997 book Jefferson's Children: Education and the Promise of American Culture [Doubleday Publishing]). But the visual and performing arts, scholastic areas traditionally framed by America's corporate-guided educational establishment as the mere realm of decorative indulgence instead of, as Botstein sees them, the indispensable mirror of humanity, are firmly at the core of his concepts. "How do you measure a free society?," he asks. "By its art. The ultimate, last bastion of freedom is the right of the artist to express his or her self. I just returned from conducting in Moscow, and when I was there I heard about the Russian government cancelling a production of Wagner's music on the grounds that it was 'offensive to religion.'" He shakes his head in disbelief.

"At concerts and in classes I want the audience and the students to discover something new in themselves by hearing and seeing the music being performed, to have a sense of wonderment and to treasure the possibilities of the human imagination," says Botstein. "I always knew I wanted an occupation that wasn't dependent on physical age, one I wouldn't have to retire from. I'm very happy I found it."

Gustav Mahler's Ninth Symphony will be performed by members of the American Symphony Orchestra and the Bard College Conservatory Orchestra, and Bard faculty conducted by Leon Botstein on May 17 at 3pm in the Fisher Center's Sosnoff Theater in Annandale-on-Hudson. Admission is free, but reservations are required. (845) 758-6822; Fishercenter.bard.edu.