This will sound odd, perhaps, but when this crisis began my real worry wasn't that I would fall sick. My greater fear was that I wouldn't be able to get food for my kids. It was perhaps irrational, this fear. When I went to the large grocery stores in Poughkeepsie, I saw that people were tense. Some appeared to act in a near frenzy. I blamed myself when I saw that there was no chicken to be found on the shelves and no canned beans either. Not even any tofu, which baffled me for some reason, and certainly no wipes or gloves. For a few days, I felt all my fears had come true. I began to think I would have to serve my family canned sardines for a few weeks. I'm exaggerating a bit, but not by much.

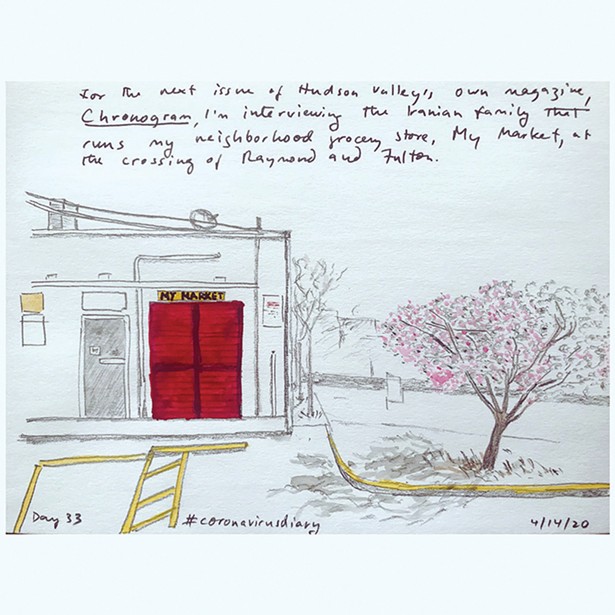

Then I stopped by my neighborhood grocery store, My Market, at the corner of Raymond and Fulton in Poughkeepsie. I live across from Vassar College campus and this grocery store is a five-minute walk from my house. In the past, we would go there to pick up ingredients we were missing. More than once I went there just to get ingredients for cocktails—lime, an orange, mint, soda, sugar—if friends said they were coming over for drinks. This was my routine: I would enter the store, and Ali, who usually works at the deli counter there, would ask me how I was doing. 'Excellent,' I would always answer. Sometimes, even without the exchange, Ali would see me enter and begin the chant. 'Excellent, excellent.'

Now, maybe in the third week of March, I stopped at My Market and found there all that I had been looking for. Chicken, a variety of beans, greens, even tofu. The only thing I couldn't find were gloves. I mentioned this to Mohsin who was behind the counter and he took some gloves out from the box behind him and put them in my bag. He didn't accept any payment for them.

Over these last two or three weeks, I have returned there often and the store has been a source of comfort to me. It would be accurate to say that I have come to regard the store as a refuge.

All these years, 10 at least, I have been seeing the same four people working at the store. They are three men and one woman. I talked to them today, asking questions I had never asked before. I learned that all of them are from a town called Rasht in northern Iran. I discovered that the lady behind the cash register, a pleasant woman with a bird-like voice, is named Minoo. She said that business is down; they only have one-fourth the usual number of customers. Most Vassar students, eager customers of breakfast food and chips, are no longer around. Those items are not selling now. Nor are items like medicine or shampoo. But toilet paper sales are up.

I asked Ali what the news was from Iran. That country has been particularly hard-hit. He said he has family there and he checks in with them on FaceTime. Things there are just like it is here. I didn't press him for details. We were both talking with our masks on. I then asked Ali if any customer had been rude or said anything racist. He said no, everyone has been nice.

I'm glad that My Market is open for us. And that the four friends who work there are wearing masks and gloves. Today I saw that they had erected a plastic sheet in front of the cash register for protection. The people who are providing most of the essential services to all of us are hardest hit by COVID-19; they are also, overwhelmingly, working-class people of color. As I was writing this, I read of a 27-year-old grocery store clerk in Maryland, Leilani Jordan, who has died from the coronavirus. Earlier, she had complained to her mother that her employer, Giant Food, didn't provide masks or gloves. Jordan was forced to bring her own hand-sanitizer to work. After the young woman's death, Giant Food gave her mother a certificate for Jordan's six years of service and a paycheck for $20.64.

Amitava Kumar is the author of the novel Immigrant, Montana and, most recently, Every Day I Write the Book: Notes on Style.