The night before I entered the old-growth forest I dreamed of fallen trees the size of tractor-trailers. I remembered the dream later in the day while I shimmied over huge boulders wedged into the side of an inhospitable ravine.

Members of the New York Old Growth Forest Association (NYOGFA) were on a mission to date ancient hardwoods in the Palmaghatt Kill Ravine in Minnewaska State Park and I tagged along to observe. Fred Breglia, president of the Association and team leader, has penetrated this difficult terrain many times during the last three years on excursions to date the forest. Many hemlocks are over 400 years old, and Breglia once pulled a core out of a dead hemlock that had grown for 517 years. The oldest documented red maple in the state (338 years) was also found here. These findings have stimulated interest in the forest by a variety of organizations such as Save the Ridge and the Tree Ring Lab at Columbia University, which verifies the oldest tree for each species in the Northeast.

Our team consisted of the passionate and the curious and was as varied as the forest we investigated. Inventor Daniel Karpen hiked in large wooden clogs with pointed toes. He wore a vest bulging in the rear with grapes, papayas, bananas, and oranges. A Canadian biologist living in upstate New York, Dr. Dean Fitzgerald sports a tattoo of a maple leaf over his heart and one of a perch on his bicep - in honor of his fish-related doctoral studies. Fitzgerald's girlfriend, Carmella Smith, and their friend, Scott Tucker, had volunteered to record statistics. The Association's photographer, David Yarrow, showed me an aerial infrared photograph of the ravine which resembled a magnified liver. Marcine Quenzer, an artist inspired by Native American traditions, also volunteered for the day. Lou Sebesta, an urban/community forester, extracted samples with the NYOGFA's president, Fred Breglia. I followed, trying not to fall into holes while scribbling in my notebook.

It's no wonder Minnewaska State Park officials keep the ravine off-limits to the public. Hikers and bicyclists on the cliffs above never guess that just below them is something special. To most it wouldn't be. But to scientists, biologists, and arborists this is a unique and magical place. Because of the harsh conditions it has never been logged, and it is almost never visited. Left alone, it is a precious ecosystem, full of answers biologists and foresters ask themselves like, "How long can a red maple live, anyway?"

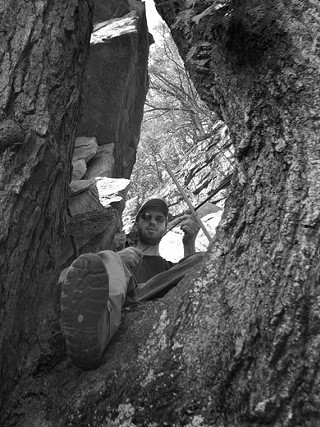

Walking to the access point, descending the steep and rocky cliffs into the ravine, and hiking to our destination to find the trees Breglia had scouted on previous trips took 10 hours. We skidded down through the upper forest and arrived at a hole between rock outcroppings through which a 12-foot drop led through the cliff to a steep slope below. Rough and unmanicured, each step was hazardous. Scrambling over boulders, branches, and moss was equally perilous to the rare plant species beneath us. Stretches of forest flattened by wind and ice storms had created a fortress of fallen logs to be navigated. The forest floor - thick with decomposing debris - often gave out to knee-deep holes. By the end of the day we were dented, bruised, bumped, and bleeding. But we had found one tree that excited Breglia.

Old growth forests are not always recognizable and they are not necessarily a forest of outrageously large trees. Clues are interpreted to determine a forest's age. In this forest we saw tiny tree seedlings growing on rotting logs ("nurse logs," Breglia calls them), many medium-sized trees, and a minority of enormous trees. Bizarre growth forms, such as spiraling bark, are signs of senior citizen trees - as are buttressed root systems, and once-smooth bark which has become shaggy or once-rough bark which is now smooth. An abundance and variety of ground covers is another sign - we saw painted trillium and rare dwarf ginseng, and in the summer three-foot tall ferns grow here. Fitzgerald, the biologist, said paper thin lichens growing on outcrops of rock could be 100 years old. Valuable wood species like the few American chestnuts and the one black cherry we saw are other signs of an undisturbed forest.

It is known that trees - like humans - have a life span, but until they are observed and documented, their ages can only be approximated. In society's march of progress we often erase evidence of the natural world. NYOGFA seeks to unravel the mysteries to which we have almost lost the answers. Their findings are offered to preservation societies who use the facts to help protect rare environments.

"We have a sense of the landscape which is based on our here and now and a sense of awareness which is based on the surrounding reality. Back in the 1750s, when George Washington was alive, they were cutting down sycamores that were fifty feet around - now we're lucky to find one that's fifteen feet," Fitzgerald said.

To discover a tree that ends up being an age champion holds some prestige. Karpen (discoverer of the 338-year-old red maple) hurried ahead until he was almost out of sight. Breglia yelled to him that we were headed up the ravine and not down to the lower bog..

I forgot about Karpen when Tucker announced a different kind of discovery: a rock cave as tall as a two-storey house with a twelve-foot entrance in the cliff. On a day when we sweated and sweltered in t-shirts, icy water bubbled out of the bedrock. Standing inside the cave - just before the black depths - our hot breath misted in the cold air.

The oldest red maple we saw that day was a tree I would have passed, oblivious to its significance. But Breglia became animated when he spotted the extremely shaggy bark. To determine the tree's exact age, a core sample was extracted using a tool that looks like a large and thin T-bar corkscrew. Breglia and Sebesta aimed for the center of the tree and twisted the tool until the boring shaft disappeared. They then pulled the sample out and stored it in a drinking straw. (Breglia says the small hole will self-seal without harming the tree.) Back at NYOGFA headquarters the sample will be glued into a groove of a wooden block, sanded flat, and each ring will be counted using a magnifying tool and a pin. The rings collected today will also be sent to the Tree Ring Lab for official documentation.

After Breglia measured the width and height of the maple, we realized it had been a few hours since anyone had seen Karpen.

"Maybe he lost a clog in the bog," Breglia said.

After the shaggy red maple, Breglia was content with our findings for the day. The maple is definitely one of the oldest in the state and if it doesn't break the age record it will be close. Evening approached and we climbed out of the ravine and up to the parking lot. There we found the missing Karpen eating grapes. We drove to a nearby restaurant for beers and discussion. There, Breglia and Sebesta counted the rings on an oddly shaped wooden wall clock. Breglia said to me, "See that unusual shape? It's a cross section of a buttressed root system.