The incident highlights conflicting perceptions of the crew’s work. “[The city] called it graffiti,” Perry said. “Nobody in the neighborhood would have called it graffiti.”

The line between graffiti and street art remains a blurred one. Both appear on the street and both use the same medium, spray paint. But Dwell, who admires graffiti, says that though the two aesthetics share some commonalities, graffiti is a distinctly different skill with a different set of rules.

Graffiti is primarily names and writing, and was coined from the Italian word graffito, used to describe the inscriptions on early Roman walls. Graffiti evolved into a way gangs marked their territory, but, according to Dwell, the current graffiti scene has little to do with gangs. “Gang graffiti went out a long time ago,” he says. “It’s more like people have a name and they want to see it as many places as possible. It’s like a game.” Graffiti artists also challenge one another, matching their skills against others in ongoing, anonymous competitions. They vie for space in “yards,” or areas of high concentrations of work, hoping to put up pieces that will be admired and preserved by other artists. If people like it, other artists will let it stay, but if they don’t, it will get painted over.

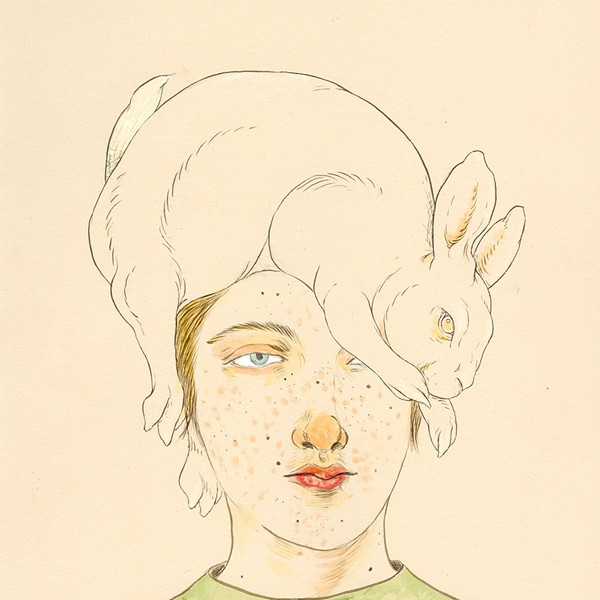

In contrast, artists like Dwell, Unit, and Mr. Prvrt rely on images more than words to convey their message. Graffiti is often made on the spur of the moment, whereas street artists spend hours preparing their intricate stencil pictures before going out on what they call “an installation.” Their art has opened doors to galleries and other venues, including Albany Underground Artists, Albany International Airport, the Kismet Gallery and, most recently, the Spectrum. In August 2006, Albany Center Gallery hosted the crew’s “Playful Maidens of the Spray” exhibit. Executive Director Sarah Martinez invited them to do a show after she saw their work on Delaware Avenue and at local art events.

“The mission of the gallery is to bring art to the public, and in my opinion, with their street art, nobody does it better,” Martinez said. The highly attended “Maidens” show ran for six weeks, and was the gallery’s most successful show in terms of both sales and attention, she says.

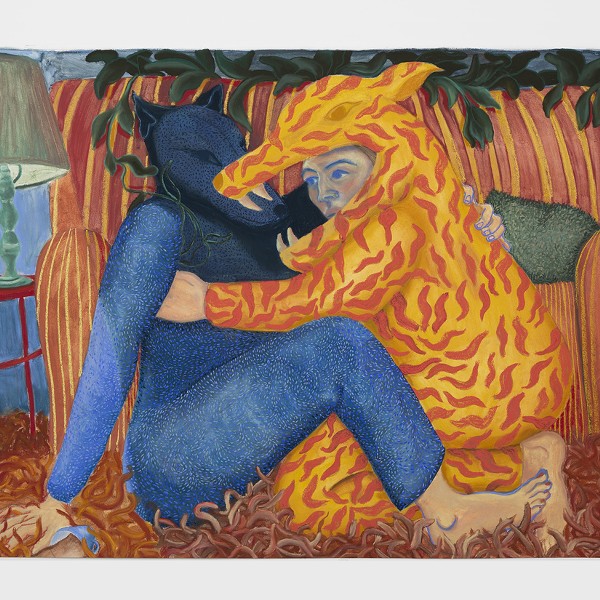

The tension between working inside the establishment and outside the law—what Martinez calls “the light and dark sides of their work”—is a critical element of the crew’s success. Art should create this tension, Martinez says.

“Look at the history of art—artists have always played devil’s advocate,” Martinez says. “Yes, what they’re doing is illegal, and there are some morals involved, but if you look at the broader picture, they’re saying something important.”

The group has an ambivalent relationship with the gallery scene. Its members see the two settings working together, but disagree on the cause and effect—whether the gallery shows keep the street art moving or the street art makes the gallery shows happen. The main goal for all three is to make a living off their art, and they realize that selling their work or being hired to do projects is a way to do that. The question is, at what cost? Ideally, they would make enough money so that they could afford to be choosy about their projects. “That’s ultimately the way to go,” says Unit, “to get paid for your art, and not compromise too much.”

All three artists are committed to continuing on the street, even if it means risking arrest, which they accept as an eventual certainty. “It’s a numbers game,” Dwell said. “We’re going to get caught at some point.”

When they do get caught, they say, they’ll have no regrets, because their mission is noble and their work valuable.

“You have to know what you’re doing is not wrong,” Dwell said. “You have to feel like you have the right to be there.”