“I can’t actually imagine that I made all this,” Mary Frank admits, looking around at her retrospective, “The Observing Heart,” at the Dorsky Museum. I know what she means. The show comprises more than 125 pieces, spanning 66 years: sculptures, paintings, posters, tryptics, cylinder seals, drawings, prints (some mounted on aluminum). “Mary is a maximalist,” explains curator David Hornung. There’s even a painting on a large scalloped fungus. The most recent piece is from last year. At the age of 88, Frank is still a working artist.

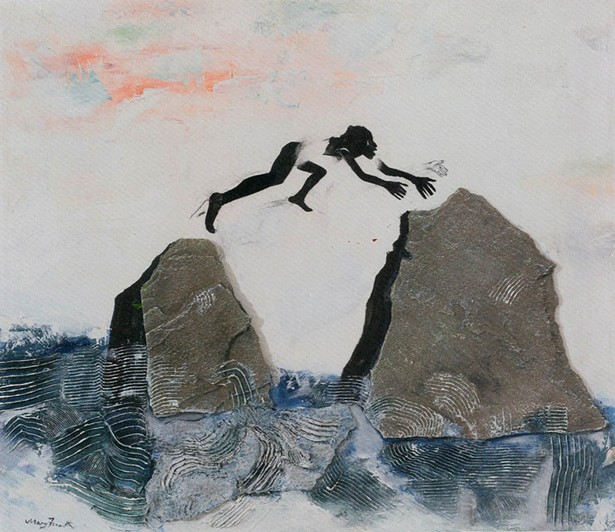

Mary Frank was born in England in 1933, but was sent to live with her grandparents in Brooklyn at the beginning of World War II. She studied modern dance with Martha Graham from 1945 to 1950, and one can see the imprint of dance on her work. The figures Frank paints are usually in motion—often sweeping motion.

At the age of 17 she married Robert Frank, the celebrated Swiss photographer. She appears in Pull My Daisy (1959), the seminal Beat film starring Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gregory Corso. One of her first art teachers, circa 1950, was Max Beckmann, the German expressionist. Frank remembers Beckmann looking at one of her life drawings and saying: “It is psychologisch very good”—psychologically admirable.

Frank made figurative art during the era when abstract expressionism reigned supreme. One senses that these images seized her and forced her to paint them. “The buildings look like they’re carved out of rock. The people are almost priestlike, like oracles,” Hornung observes. Frank creates a sacred zoology: big-eyed wheeling owls, a horse with a snake’s tail, a rising crane lifting its wings. I was reminded of the artwork our Paleolithic forebears painted in caves 30,000 years ago. One can imagine these paintings functioning like Tarot cards, as a form of divination. “Mary believes in magic,” says Hornung.

Frank draws on diverse art influences. Some of her large paintings—such as What Color Lament? are divided into smaller rectangles, with scenes inside, like a metaphysical comic book. Others have tiny figures reminiscent of Chinese scroll painting. Breath, for example, shows a head in profile breathing out a sea, in which nine small silhouetted people—perhaps a family?—are foundering.

For decades, Frank has divided her time between Manhattan and the Hudson Valley. This has affected even her choice of materials. There’s a collection of paintings made on jagged pieces of bluestone: a startled monkey, a polite octopus, a crouching human with a bird’s head. These pieces are propped up on metal armatures on a table, like pages of a stone sketchbook. Some of the paintings, such as Knowing By Heart, have painted bluestone attached.

Works in “The Observing Heart” are from Frank’s collection, her gallery (DC Moore), from private collectors, plus loans from two museums: the Everson in Syracuse, and the Whitney. The show is part of the Hudson Valley Masters series at the Dorsky, which began in 2001, and has included such major artists as Carolee Schneemann, Raoul Hague, and Judy Pfaff. The documentary Visions of Mary Frank, directed by John Cohen, is on view.

Frank is a longtime activist, and her work may be seen as intrinsically political. Frank’s posters—which I have seen at demonstrations, carried by angry protesters—effortlessly merge with her larger body of work. One includes the phrase “Schools Not War,” beside a painting of a soldier cradling his dying comrade. “Her poster style is very coarse and urgent,” Hornung observes. Frank is happy to see her art marching in the streets.