Before launching headlong into 2021, with its gooey center of possibility and optimism, we wanted to take one look back on this Dumpster fire of a year. In early December, we invited writers to share their tales of loss from the past year. To our delighted surprise, some even turned the tables on COVID, telling us not only what was lost, but also what was gained during the pandemic. Goodbye 2020. We hope not to see the likes of you again.

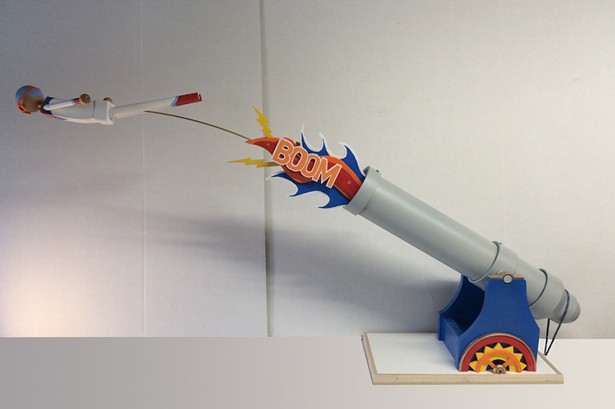

Special thanks to Brent Felker and the Arts Society of Kingston for sharing images of work from the upcoming exhibition "Hindsight is 2020," on view beginning January 2.

—Brian K. Mahoney

FRIENDLIEST SENIOR GIRL

Being from Texas means I get to see family usually twice a year, around the holidays and in the spring or summer, when invariably one old friend or another gets married. I always make the effort to visit the swollen suburb where I grew up and where, until this year, my mom still lived.

This year was different. I didn’t attend a single wedding. And the only time I’ve been to my home state was to help arrange the funeral and settle the estate of my mom, who died on July 30.

She was 59, and her death was unexpected. No denouement, no goodbye. So that’s one thing I lost in 2020. Then there are other losses, cascading into the future: The time she had to grow old. Her first time holding her grandchild. Trips to Yellowstone, Seattle, New York City that we talked about but never took.

But I gained something, too. Among the rooms of personal effects my brothers and I sorted through in that feverish, unreal week were boxes of photo albums, letters, and keepsakes my mom had held onto over the decades. Some were familiar to me, but most I had never seen before. They trace a person I could never really know—my mom before she was a mother; before she met the man who would become my dad; before she was a person who would go on road trips in college and win Friendliest Senior Girl in high school; before she was a little gap-toothed girl with her whole life ahead of her.

I can’t quite find her there, try though I have. But she is recognizable: the smile that lit up a room, the kindness toward others, the optimism and hopefulness. If there was ever a year that called for those qualities, it was this one.

Phillip Pantuso is the managing editor of the River Newsroom.

IMPERMANENCE

I've lost the illusion of permanence. It went missing in March when my freelance writing gig dried up and took my 70-year-old identity with it.

I came to the craft of writing late in life and was fortunate to enjoy some minor success in having regular assignments: to write about who people are, what they’re doing, and what’s happening in this culturally rich place we call home.

Earning a weekly paycheck at this for a dozen years grounded me and made me feel as though I could build on this career in some modest way. I felt I belonged in the community.

A student of Buddha’s teachings, I’ve understood for years that everything changes, all things pass, nothing is permanent. And I’ve experienced enough loss in my personal history to get the concept of impermanence at the contextual level. The fallout from the pandemic—and the highly stressful, polarized sociopolitical backdrop—should not have taken me by surprise.

But they did.

I did not expect, could not imagine, witnessing such dysfunction in my world. I’ve always operated under the illusion that human consciousness would continue to evolve, and we’d learn to live happily, healthfully, forever after.

I’d love to think the hell we’ve recently endured is simply a blip, one that may permanently alter the ways we interact with each other but also opens each of us to some core sense of our humanity.

Dare I now hope for a good ending to my own and our collective story?

Ann Hutton, who has completed two as-yet-unpublished memoirs, leads a weekly writing workshop for the oncology support program at HealthAlliance Hospital in Kingston and edits the work of a select few writing clients.

SEE YOU IN A SWEATY DIVE

I didn’t have to think too long about what I’ve missed most since the start of the pandemic. Sure, I’ve missed socializing and going out to eat frequently. I’ve even missed the gym; I do what I can by lightly exercising at home and running when the weather’s decent, but I still feel like I’m not doing enough to counteract those late-night ice cream binges. And, yes, I’ve missed visiting my family. But what I miss most of all is simply being able to go out to see a live band or two. And making music in public myself.

As someone who’s been a musician for over 40 years and given his life to music, the music community is my extended family, with members not just locally, but around the world. I miss bumping elbows with them in sweaty dives. I miss DJing to appreciative dancers. I miss creating sound and being swept up in a tornado of volume that rips the roof off the joint.

Before COVID, people had largely been taking live music for granted, blowing off gigs because, oh well I’ll go see them next time and I can just stay in and watch a YouTube video because that’s just as good. My hope is that once we’ve all been vaccinated—and done our part to slow the spread of the virus via masks and social distancing—and venues reopen, more people will have finally realized that live music is not a given: It’s something to be treasured. For the generation of kids who were just getting to the age where they could go to shows only to have the opportunity suddenly yanked away, perhaps the idea of seeing live bands will even become the hip new thing. Once stages do return, I’m looking forward to a hell of a party.

Peter Aaron is Chronogram’s arts editor.

A SEASON OF GRIEF

I didn’t lose my miniature pinscher, Lily, because of the pandemic, but losing her during the pandemic made it that much worse.A rescue from a hoarding situation, Lily had been with me nearly nine years, since she was about five. For the first few years, we were inseparable, due largely to the fact that she bonded to me like glue and had severe separation anxiety. Time apart caused her so much anguish that it was just easier to slip her into a mesh doggy bag and take her everywhere I went.

That included Vassar Brothers Medical Center when my mother lay dying from complications of dementia just before Christmas 2013. Lily was my bridge to my mother, and I considered her my only remaining close relative. At my mother’s apartment, Lily would rush to my mom and hop on her lap, exactly as I had imagined her doing before I adopted her. Once, when I asked my ailing mother whether she still experienced joy, she responded, “When you and that little thing walk through the door, it makes my day.” Lily made my day, too. She battled heart disease, partial paralysis from a blood clot, and chronic kidney disease. With each setback, she seemed to come back stronger than before, until the day after Thanksgiving, when she succumbed to kidney failure.

I miss my mom. I miss Lily. I miss celebrating Christmas with the woman who embodied the holiday spirit and the tiny dog with the big heart. And though the pandemic didn’t take either of them, the incalculable losses it has caused, the isolation, and the constant stress of trying to stay safe intensify my grief and longing.

Karen Angel is a freelance writer in New Paltz.

PRIDE & PRIVILEGE

Way back in mid-March, when life as I knew it ground to a halt, I breathed an audible sigh of relief—not because I had stocked up on toilet paper, disinfectant wipes, and pantry staples (I hadn’t); rather, it felt like the proverbial pause button was pressed (something I rarely do of my own volition).Over the past 40 weeks, I have lost an overwhelming sense of obligation to do and instead I’ve learned to be. My kids and I have logged dozens and dozens of miles on foot (and recently snowshoes); cooking dinner has (finally!) become a family affair; and I've traded the hours I used to spend driving teaching my kids how to play backgammon and (re)learning how to do two-step algebraic equations.

There is suddenly time to connect with my aging parents who live next door: some days to watch "Jeopardy!" together (we don’t have a TV) and other days to simply raid grandma’s freezer for Klondike bars. We’ve even resuscitated a weekly family dinner—the one caveat being we carry the meal next door, as my dad is newly confined to a wheelchair. I feel equal parts pride (I’m a single mom raising two teenage daughters) and privilege (I am a self-employed homeowner who has been able to keep food on the table) when reflecting on the bulk of 2020. Mostly, I’m thankful my greatest loss of this past year was something that needed to go.

Hannah Van Sickle is a Berkshire County-based freelance writer and regular contributor to Berkshire Magazine, Litchfield Magazine and the Berkshire Edge.

GRATITUDE

Loss has been rampant this year, but so has gratitude. My friends now mean more to me than ever, for of the many things that I miss because of imposed COVID-19 restrictions, one of the dearest, is get-togethers with my pals. Coffeehouse hangouts, shopping trips, diner dinners, salon stays, at-home visits—I miss them all. I want to feel the presence of my friends; how the air around them becomes charged with their being. Sure, I can get a sense of them through cell calls and video chats, but those provide just a smattering of their essence.Being together physically is tangible. Sharing the same space with my friends takes us beyond chats and images of each other. We also share touches, likes hugs, pats and pecks on the cheek. We smell our perfumes and familiar aromas, like coffee and nail polish and steaming bowls of chili, for richer, more real, connections. I miss them.

Hopefully, we’ll be together soon. In the meantime, I now realize that life isn’t about what I thought I had, but about what I experience, what I learn from those encounters and how I move from one to the next in hope and wonder.

Karen Maserjian Shan is a communications professional who lives in Poughkeepsie.

BREACH

Many of the places I’ve written about for Chronogram are places that I’ve hiked with Adam Ovadia—we’ve stood above the Hudson River on the cliffs of the Palisades, we’ve been caught in the snow in the Adirondacks—twice—and we’ve hoisted ourselves up onto erratics in Mohonk. I know the term erratics—boulders hefted into surprising positions by glaciers—because of him. COVID kept me from making the trip to New York City for a face-to-face goodbye with my friend before he moved to Colorado.

There aren’t many people like Adam. Looking out at New York City, he has said dryly, “It’s beautiful—except for the buildings.” He knows the right spot in Harriman to pick blueberries. And he’s better at identifying plants—including edible plants—than anyone I’ve met. To know about forest plants—to care to know—is rare. Many people hike, but few drink in the woods as Adam has.

We once made our way to where Hurricane Sandy blew a hole in a barrier beach. We stopped to observe the bisected land—a stretch of beach we’d hiked across several years before, now obliterated. Were it not for COVID, we might have had the chance for a drink before he moved, on his 22nd-floor veranda in Marble Hill—near the Harlem River Ship Canal—a channel a little like the wilderness breach. It joins the Hudson and Harlem Rivers, letting ships make their way around Manhattan Island to reach their destinations.

Ian Halim grew up 10 miles from the Hudson River in Yorktown, and fell in love with the Catskill Mountains early—from his first car excursions north as a little kid to see his four grandparents in Margaretville. He is a freelance writer and resident physician now living in Massachusetts.

THE LOST CHILDREN

I told them I’d take care of them until they didn’t need me any more. I told them I was fearless and tough, and that nothing frightened me. I told them, “See ya Tuesday,” just as I always did on Thursday evenings, headed home from an exhausting day of home schooling, diaper changing, meal prep, and endless laundry. And when I said it, I meant it.

And then I read the news. It was March 12. And the whole world was suddenly going underground. I had become sick twice already in two months from working in a Petri dish, because that’s what nannies deal with. I had purchased an N-95 in February and was already wearing it then. I was well aware of the viral threat long before this night. But as I contemplated my age, medical history, and recent brush with death, an emphatic current buzzed through me and the decision seemed to make itself in a flash.

I may never see those three children again. I have wept. Ten months later, I’m still wrestling with guilt and despair, and the horror of what my girls must think of me. The perfect baby won’t have a clue. I vanished. But I’m still here.

COVID killed my decade-long profession. But even more so, it made me a liar and a coward. Didn’t it?

Haviland S Nichols is a writer, editor, caretaker, budding archer, and peddler of metaphysical supplies on Instagram @gnosis.magick.

LOST OASIS

The pandemic put an end to Kingston Writers' Studio, the small co-working space for writers that I opened in 2017. Initially located in the Opera House building in uptown Kingston and later relocated to the Fuller Building in midtown, Kingston Writers' Studio was a little oasis, something I started mostly because it was what I needed—a place to work outside of my home where I could cross paths with other writers, socializing and networking with them, getting more focused and accountable to my work in their presence. The studio was never profitable. The only way to attract writers was to keep it super affordable, and so I lost money on it. But it was worth it for me, professionally and also socially. As an introvert/extrovert hybrid, I have always preferred the serendipity of running into people and igniting future plans from there to the tedium and riskiness of reaching out to friends and colleagues to initiate plans. So, I really miss bumping into people there, at Rough Draft, and really...everywhere. I miss seeing close friends, but also acquaintances, and the mood-boosting happy accident of crossing paths with them unintentionally—something that's close to impossible right now.

Sari Botton is a writer and editor of the award-winning anthology Goodbye to All That.

LIVE YOUR LOVE

Last spring, I started editing SrutiRam’s (George Palmer) memoir, All Roads Lead to Ram: The Personal History of a Spiritual Adventurer (Monkfish Book Publishing Co.; to be published next June). It was the perfect antidote to the shutdown—comforting and distracting. SrutiRam’s voice was devout, sincere, mischievous, mercurial, wry. He’d had Neem Karoli Baba as guru, Ram Dass as teacher and friend. He’d left a career as a high-powered hairstylist to seek God, and he’d won international fame as a singer with the group Sri Kirtan along the way.

SrutiRam was exacting, but I earned his trust. Just before Thanksgiving, he said, “When this pandemic is over, I want you to come to my house.” He’d written about his Woodstock house filled with crystals, altars, and Indian art. It sounded magical. “I would love that,” I responded. Looking forward to things is one way I’m getting through the pandemic. I held on to his invitation like a rare gold coin.

But SrutiRam didn’t tell me he was having COVID-19 symptoms. Soon after we spoke, he was hospitalized. For two weeks, I listened to Sri Kirtan, sad but hopeful. After he died on December 16, I joined over 150 heartbroken friends from across the country on Zoom to memorialize him with music and stories of his caretaking, joking, generosity, impetuousness, and capacity to “Live Your Love,” as the Sri Kirtan song goes.

Since then, in dreams, I’ve discovered someone who looks like SrutiRam in a big white house and watched him open hidden doors leading to even bigger rooms. So maybe I’ve met him after all. Or else I’m just missing the friend I’ll never have.

Susan Piperato is a freelance writer and editor living in Kingston.

BEING OPTIMISTIC

All my life I have forged forward with optimism. Believing that being a good human mattered and that the reward for that hard work lay in the simple things: a family to love, a house to live in, food to eat, good health, and a job that allowed for it all. I also believed that collectively as humans, through kindness and understanding and common goals, that we could make our planet a more peaceful, habitable place—for everyone.I know that may sound naive—and of course is—but those beliefs took me to amazing places in my life; literally and figuratively, and taught me so much about what it means to be alive and collectively living on this planet. But this past year of living with a deadly virus amidst such enormous political turmoil and treachery, has made being optimistic an elusive and evasive feeling for me. One that I miss desperately. After almost a year of not being able to gather, to travel, to look into one another’s faces, into new faces, without fear gripping us at the core, it is getting harder for me to imagine when a feeling of hopefulness about our future will return.

I long to be able to tell my children with an optimistic, confident heart that the future will be bright and in fact better because of all of the hard lessons we are learning in this moment. And, even with my own fears in the way, I will. Because at this moment, there is no other way to try to be.

Jane Kinney Denning is an acquisitions editor for Mango Publishing Group and past president of the Women's National Book Association.

CASUAL LIES

At some point after my siblings and I all had steady income streams, we began taking mom for dinner on Christmas Eve. To thank her for all the holidays she cooked, was in the midst of cooking, would cook for holidays to come. To show mom her kids were okay now, we were self-sufficient enough to afford to take mom out for a fancy meal.

For a dozen years, we sustained this tradition, my three siblings and mother and I meeting at the ancestral homestead in Queens and trekking to a mutually agreed upon restaurant, something safe, like Italian food or a steakhouse, as my family did not have adventurous palates.

As the years and meals ticked by, I lobbied my family to be more adventurous in our choice of Christmas Eve restaurant. For instance, the neighborhood we all grew up in, Bayside, was close to some world-class Asian food in Flushing, a predominantly Asian community. As I could not imagine my family agreeing to go to a dim sum palace where we might be the only non-Chinese patrons in the joint, I suggested a Korean barbecue restaurant. Dedicated carnivores all, I thought that by putting the stress on the second part of the descriptor—grilled meats—I could cajole my family into stepping outside their culinary comfort zone.

After sufficient badgering, my siblings agreed. My mother however, presented an unexpected roadblock. While she would be fine with Korean barbecue, her friend Pat (my sixth-grade teacher and a longtime family friend who often joined us on holidays) didn't like Korean food and that Pat probably wouldn't want to come if we chose this restaurant and couldn't we just go to this little Italian-Argentine fusion restaurant she found in Jackson Heights and save Christmas Eve?

We ate at the Italian-Argentine fusion place—a meal notable for both its aggressive mediocrity and expense. Why did I have to suffer a succession of suboptimal restaurant experiences? Why was I kowtowing to my family year after year? And Pat wasn't even family! By the time the bill arrived, I was flushed from wine and anger.

On the way out to the car, I turned to Pat and demanded, "What do you have against Korean food?" "Nothing, I love Korean food," Pat said. I turned to look at my mother. Like a child caught in a lie, she shrugged her shoulders, offered an enigmatic smile, and tucked herself into the car. Mom lying about Pat's dislike of Korean food became a running family joke.

Mom's been gone now almost three years now. For the past two years, my siblings and I got together for Christmas Eve dinner just like we used to with Mom. (I pick the restaurant now.) But not this year, this blasted year. No siblings, no fancy Christmas Eve dinner, no lying mother.

Brian K. Mahoney is the editor of Chronogram.

SONGS

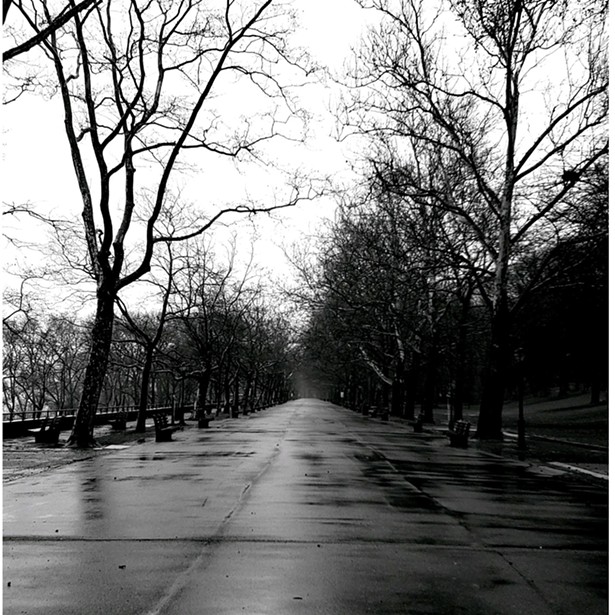

I miss a synagogue in Brooklyn. Every second week, I used to visit my father (who is 101) in Windsor Terrace, a somewhat obscure neighborhood next to Prospect Park. If I was there on a Saturday, I’d visit the Park Slope Jewish Center, the nearest Hebraic house of worship.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m an agnostic like everybody else, but I like the way this congregation sings–handsome, ancient melodies that sound Irish and Ukrainian at once. For a few days afterwards, those songs would reverberate in my mind:

etz chaim hee lamak’zeekim bah

The nice thing about songs is that you don’t have to believe in them. Whether or not you agree with “Bombs Over Baghdad,” it still makes you dance. (I’ve been listening to OutKast lately).

Sparrow is the author, most recently, of Small Happiness & Other Epiphanies.

THE ABSURD TRUTH OF THINGS

I visited the death bed of one of my best friends via phone. He was in Hawaii on a family visit, extended from a couple of weeks to many months due to the risks of flying during the pandemic. I knew he had serious health issues, ones he somehow surmounted by his indomitable will, great doctors, and with the help of his—I have to say this, there’s no other word—saint of a wife.

She called one night recently. Most often she speaks with my wife, but this time she asked for me. I knew immediately what this meant. My friend was dying.

His wife said she would hold the phone to his ear. He couldn’t speak but she was pretty sure he could hear. My friend and I had often talked of death and had found a shared black humor as we contemplated mortality together. He had a great laugh that erupted like a lightning bolt of insightful wisdom when presented with a sudden revelation of great beauty or the absurd truth of things. A couple of days later, his wife sent a video of my friend laying on his side holding the hand of his tearful daughter as his son played the guitar. My friend was smiling, beaming love.

Carl Van Brunt is a Beacon-based writer, artist, and curator.