Do you recall your first poignant cinematic memory, a visual with a psychological edge buried somewhere in your unconscious that still haunts? Stan Douglas goes there: He knows what provokes, and he wants you to remember it. Since the 1980s Douglas has been exploring a range of artistic mediums—including film, photography, theater productions, and other multidisciplinary projects—to create vivid visions that are both secular and sinister, equally lush and unsettling. On view at the Hessel Museum of Art/CCS Bard through November 30, "Stan Douglas: Ghostlight" is the artist’s first survey in the US in over 20 years and features 40 artworks that provide a compelling blueprint of his diverse practice.

Born and raised in Vancouver, Douglas studied at the Emily Carr University of Art and Design and has been exhibiting widely since his first solo show in 1981. His status as a heavyweight artist includes multiple representations at major international exhibitions such as Documenta, the Venice Biennale, and the Whitney Biennial, in additional to numerous shows worldwide. Throughout his career, Douglas has addressed the role (and eccentricities) of technology and mass media in image-making and the shaping of collective memory, as well the societal infections revealed therein.

Inspired by a range of cultural influences—from the folkloric tales of the Brothers Grimm to the tragicomic literary works of Samuel Beckett combined with certain pathologies of Sigmund Freud and spiced with the flair of Hollywood—Douglas is a master at conjuring elaborate scenes that are simultaneously alienating yet accessible. Take, for example, his titular Ghostlight (2024) photo of a single lamp in the middle of a Baroque-like empty stage, its light casting a ghostly glow that illuminates the hollow theater with a supernatural intensity. This work gets under your skin and leaves you wanting the next cryptic moment of Douglas’s narrative.

In other photographic works such as Dice, 1950 (2010) from his "Midcentury Studio" series, Douglas approached the series with the persona of a fictional photojournalist. In this black-and-white photo, three men dressed in impeccable gangster style huddle close to the ground, their taught skin gleaming amid the dramatic setting as one man tosses the dice while a small pile of cash awaits its fate. This slick image borders on a commercial recreation of a noir-inflected crime drama while maintaining an enigmatic veneer.

Other works, including Disco Angola: Club Versailles, 1974 (2012), are amusingly weird. Here we come upon a freewheeling party in an elaborate period room with a 1970s-glamour vibe, where revelers appear absorbed in a night of sinful fun. Our position as a viewer is from above looking down, and a man with exposed ass checks grooving along within the crowd of dancers disrupts the frolicsome spectacle with a pinch of peculiarity. Douglas’s ambitious performative restaging of urban events includes Scenes from a Blackout: Loot (2017), an eerie post-riot vision of a dark street with mannequins strewn in the road with a blue van parked on the sidewalk while a few city dwellers wander about, a scene of believable mayhem and randomness.

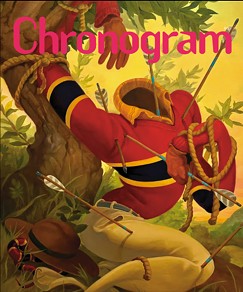

"Ghostlight" features the premier of Douglas’ new 13-minute immersive, multi-channel video installation Birth of a Nation (2025). This powerful piece revisits D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, a controversial war epic set in the South during the Reconstruction-era (1865 to 1877) and the founding of the Ku Klux Klan. This keynote work is a critical "realist" re-envisioning of one of the film’s most pivotal scenes of racial terror (fill in the blanks), and sequences with the movement and environs of the original (the minutes that I witnessed were indeed gruesome). In this and other poignant works, Douglas reconsiders decolonial struggles and legacies of transatlantic slavery.

Douglas’s art is distinctive, seductive, self-reflexive, and still open to interpretation—it provides an expansive view without telling us what to feel (because we will feel it regardless). He gives us an altogether genuine re-presentation of social tensions related to historical and cultural references and he puts us in the front-row to experience a time-capsule of strangeness for ourselves. Douglas knows how to destabilize our psyche with faux moments while offering a life raft of familiarity to navigate the realms of his gracefully haunted lands.