- Image courtesy of the Rubin Collection

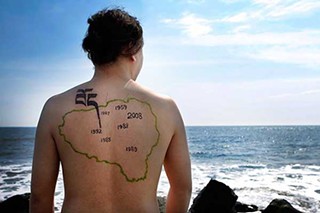

- Tenzing Rigdol, 2010, "Unhealed"

“Anonymous: Contemporary Tibetan Art,” now on display at the Dorsky Museum in New Paltz, is a fine show: large, authoritative, and—as these affairs usually go—a bit uneven.

Mostly drawn from the Shelly and Donald Rubin Private Collection of Himalayan and related Indian and Chinese art, traditional and contemporary, the show introduces us to a mode of art-making embedded, historically, in a way of making that's usually talked about in hushed, reverential tones. But now, in its contemporary guise, the best of the work on display is invested in all the formal, political, and social concerns that make good contemporary art, well, good.

“Anonymous” makes the case that you can’t understand Tibetan art without understanding the disputed political economy within which it functions and, in historical then-Tibet, functioned. Artists in the show play on their conventionally understood ancestry as they question their descendant futures, under authoritarian Chinese rule. Here, I’m thinking about Tenzing Rigdol’s strong Unhealed, a photograph of the map of Tibet tattooed on his back, years tagged as if they were the art or so many butterfly specimens displayed proudly. Rigdol’s Melong—in traditional terms a “looking glass,” it functions as a way to think about the divine, the spiritual—is a ritual diagram of China’s utter political domination of Tibet, collaged together brilliantly; its colors are compacted and concentrated, right in the center. Everything else is just beautiful decoration.

The best work on display matches its political message to superb formal and material investigations without turning ironic, solely to capture your attention. Stridently critical work is put out in rich paint and extravagant, delicate collage and installations. And, of course, there are some stars in this show. Rigdol is one of them. Tsherin Sherpa’s Protector is a rich diptych, acrylic on gold leafed canvas, a spinning painting that you think used to be a more traditional prayerful representation of both power and, well, protection. Its stunning form, traditions spun out, stands between East and West, the traditional and its now-ness, in a way that I can describe only as “satisfying”.

Now, stepping back a bit, despite the title, “Anonymous”, the show offers the argument that though all the work on display is art, the traditions behind it all functioned as craft in the service of story and reverence. That really, what we call art at the Rubin Museum was really thought of as nothing of the kind by the people who made it, by the people who supported it. So, Karam Phuntsok’s Marpa is embedding in a history that’s more about storytelling than about the visual appreciation of pictures as such. “Anonymous” is then a show about the ways Tibetan art is subverting its own history as, through art, it tries to subvert the politics that’s dominated Tibet for a generation. Lovely then that the most interesting riff on that subversion of anonymity is precisely that so much work on display is tagged Anonymous. That revelation structures much of the melancholy beauty of the show.

But don’t think this is hidebound work, coughing up dryly only on its history. Artists in Tibet are using video, installation, video-installation, sculpture, bits and pieces of ready-mades, and, of course, painting that works every way but loose. Tibetan artists are trained in the contemporary jargon; some in the show are internationally schooled and practiced and it looks it. So, walking down the galleries you might think: either most Tibetan artists doing interesting things are plying their craft and their trade at the level where all art comes out in the “international style,” ready set for international biennials, or the show picked out work that functions on those terms. I think the former and, well, however it cuts, the show has made a contribution to the way I look at the world through art.

So, then, is it that the work on display is so inoffensively postmodern (plays on history, reevaluations of this, that and the other) that the show comes off as uneven? No, it’s rather that though the work on display is inoffensively postmodern, some of the work, in particular Jhamshang’s Mr. XXX trades on the conceit of the postmodern ironist. A work about China’s meddling into international travel in and out of Tibet, the artist offers up a caricature Buddha that looks more like some Harlequin Metropolis android. And though the references are apt, the juxtaposition of those references next to traditional texts, plausibly about the reverential the spiritual, feels shallow. Dedron’s Mona Lisa feels like a Tibetan take on tradition re-fitting in this case the Western canon, spiced with a bit of the East. The work feels facile, though, yes, it is technically, materially, superb. It is this growing toll, technically superb work that takes the easy way out, that makes the show uneven. This, when so much of the work takes subversion as a serious, sincere, difficult affair.

“Anonymous” is up for a long while, until December 15th, in fact. I’m sure I’ll have seen it a few more times in the meanwhile. Do go look into it, if you can. Sure, Tibetan art is of a kind that you’d see in America, that it’s not really exotic and sandalwood perfumed. But, what did you expect?

Look for an article on “Anonymous: Contemporary Tibetan Art” at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art in our September issue.