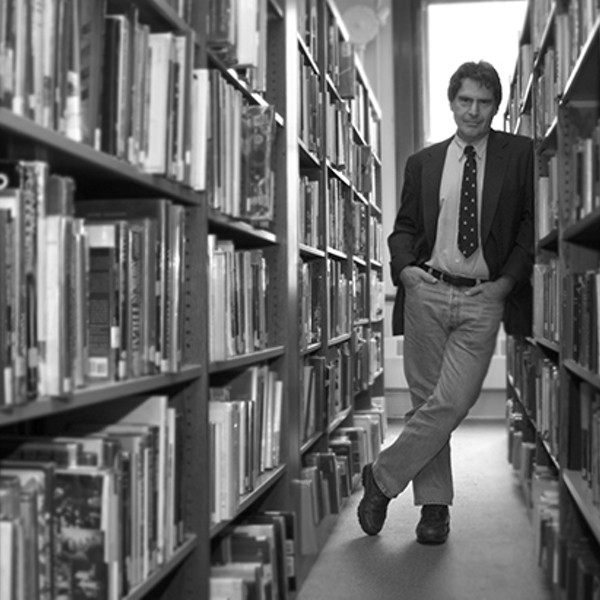

The urban studies theorist Richard Florida isn’t from the city. Born to a working-class family in New Jersey, he earned his PhD from Columbia University, taught for years at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Mellon University, and is currently a professor at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management.

Florida first came into the public eye with the 2002 publication of The Rise of the Creative Class, in which he argued that high concentrations of creative people are what drive the success of metropolitan regions. Since then, Florida’s star has continued to rise with the publication of follow-up books, including the wryly titled Who’s Your City?

Florida’s latest offering is The Great Reset: How New Ways of Living and Working Drive Post-Crash Prosperity. It frames the current economic crisis in the context of previous bust-and-recovery cycles beginning in the 1870s and 1930s, respectively. Florida argues that we are heading toward a third “Reset,” driven by the creative class and likely to produce a step-change in our values and where and how we conduct our lives.

We caught up with Florida recently to discuss The Great Reset. Here’s what he had to tell us.

Richard, you were born to a working-class family in New Jersey. No academic thinks in a vacuum. How, if at all, did your upbringing shape your take on the economic and social issues you analyze?

I was born in Newark, New Jersey, more specifically, in the Italian district of North Newark. It was a very real, walkable, ethnic Italian neighborhood. My parents then moved around 1960, when I was about three, to North Arlington, a mixed-ethnic Italian, Polish and Irish working-class suburb with migrants from Newark and Jersey City.

My upbringing has affected my thinking extensively. I watched the city of Newark, which had a quite functional downtown and neighborhoods, fall victim to racial tension and riots (provoked by the police), and collapse completely. I also watched the factory my father worked in, which employed hundreds of working-class men and women—Italian, German, Irish, Portuguese, Puerto Rican, Hispanic, and Black—begin a long decline and ultimately shutter its doors. These were my fundamental influences. I wanted to make sense of this. After I read all the books in my Catholic school library and local public library, which took me to the age of about 13, my father started taking me on weekends to the Newark Public Library, where I would peruse the stacks and read everything I could about urban affairs.

The Great Reset seems to have been written in part to provide a sense of perspective on our current depression—a word I use in both its psychological and economic senses. In a time when people feel daunted, to put it mildly, by our economic circumstances, The Great Reset appears intended to provide a sense of context—and also some optimism. Is this a fair assessment? Why should we feel optimistic?

Economies and societies invariably remake themselves in the wake of a crisis. It’s a necessary component of rebound and recovery. Outmoded industries and tired consumption habits make way for new goods and services, and for new careers and forms of employment. Meanwhile, the population realigns itself in the landscape. All these developments are connected to lifestyle changes. Each of the previous two Resets—one in the 1870s, the other after the Great Depression—were vibrant periods of innovation. Inventors and entrepreneurs rushed to fill the voids left by struggling industries with new ideas and new technologies that led to new forms of infrastructure such as railroads, subways, and highway systems. All that innovation powers economic growth. The same thing has to happen today—and if past is prologue, it will. The new core products of the creative age—biotechnologies, educational services, entertainment, and information—need to fuel our future economic vitality.

At this moment one-fifth of Pakistan is under water. There’s this thing called climate change, and though our media and citizenry are doing a superb job of denying this, it’s already at a theater near you. Global warming isn’t mentioned in your book. A plausible case could be made that if your analysis had included this “exogenous factor,” your conclusions would be much less optimistic. Your thoughts on this?

We have to live better and be better environmental stewards. As I meet with city officials and economic development leaders, my message about sustainability is clear: Sustainability has to be a common practice rather than an added value in the future. Many of the economic forces—the concentration of assets, for example—will require us to evaluate our choices and needs more holistically. For example, infrastructure will have to develop and adapt to our new economic reality. Green buildings, better urban planning, and more recycling are already changing the way we live and work in our communities. We will see a return to denser communities and more value being placed on walkable communities—this will be critical to the revitalization of many of our outlying suburbs and communities that are deteriorating.