The fate of New York’s energy future may rest on the tiny Columbia County town of Copake, where a community battle between a solar power developer and town government might be a bellwether for how the transition to renewable energy may unfold across the state. A town lawsuit filed in response to the project, if successful, would put a halt to the state’s new system for approving large renewable projects.

But beyond the legal dispute, the fight over solar energy in Copake is a powerful illustration of how complicated things can get when environmental goals collide. It’s also an example other rural upstate towns should be paying attention to, if they want to keep some local control over the shape and size of large energy projects.

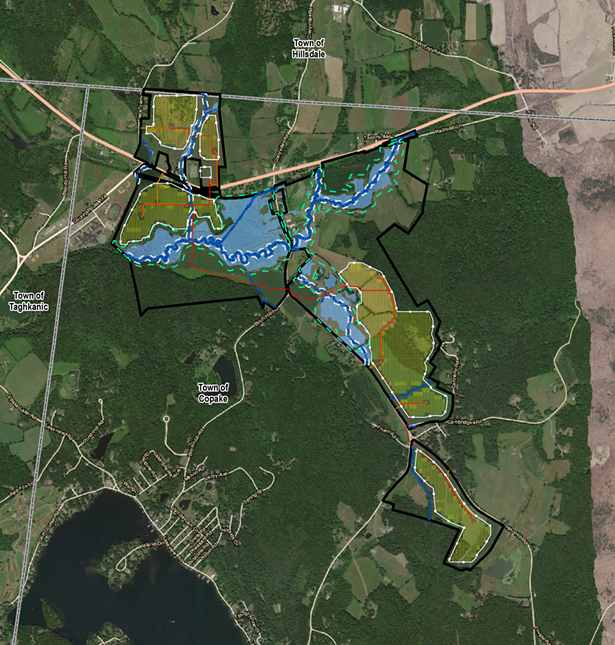

The proposed solar project in Copake—dubbed Shepherd’s Run, in a nod to the area’s agricultural heritage—has been a lightning rod for community disagreement since 2017, when Chicago-based developer Hecate LLC first approached the town board with a proposal to build 40 megawatts of solar power capacity, which was later increased to 60 across 480 acres. The project would place large solar arrays across a number of different land parcels leased from local landowners, in an area that spans farm fields, wetlands, and forest.

Copake is a small farming community with Berkshire and Catskill vistas, nestled along Columbia County’s eastern border. Preserving its agricultural heritage, scenic beauty, and active farmland are among the central goals of the town’s comprehensive plan. Copake’s solar law encourages small-scale solar development as long as it harmonizes with the rural landscape, but places significant constraints on larger projects.

In response to intense community pressure, Hecate has downsized the project twice. The proposed footprint is now down to 245 acres, with panels they say will be confined to 80.8 acres. The developer has indicated that it is open to further, though limited, downscaling. But with both sides dug in, and a legal battle unfolding, it seems unlikely that any proposed plan will satisfy everyone.

From the outset, Shepherd’s Run has pitted neighbor against neighbor, and emotions around it continue to run high. Lawn signs both supporting and opposing the project sprout along Copake roadsides. Full-page ads paid for by battling ad hoc groups have appeared in the local Columbia Paper.

Shepherd’s Run supporters call opponents NIMBYs—not-in-my-backyarders—and argue that Copake needs to get real and accept the inevitability of large-scale renewable projects. “We are in a climate emergency,” says Juan Pablo Velez, cofounder of Friends of Columbia Solar. “We need to deploy renewable energy fast. If we don’t, we will have categorically bigger problems with hurricanes and droughts and flooding that will make the issues we are debating around Shepherd’s Run seem minor in comparison.”

Copake Town Supervisor Jeanne Mettler is quick to defend her board’s opposition to Shepherd’s Run, and its move in June to sue the state over the project. “We understand climate change is an existential threat, and Copake is supportive of renewable energy,” says Mettler, an attorney who grew up in town. “But we are opposed to the construction of this project as it is currently sited. Quite frankly, to dismiss us as NIMBYs is really insulting to what we have tried to do over many years: to balance the need for renewable energy with our role as stewards of our rural landscape, wildlife habitat, and natural resources.”

Mettler and her town board are also concerned about the impact on tourism, a staple of the town’s economy, and on real estate values. The latter is also on the minds of many local residents like Bill Leonard. He has lived in Copake since 1994 across Route 7 from one of the parcels where Hecate hopes to site Shepherd’s Run.

“There are two giant fields across from our house and they will be filled with solar panels,” Leonard says. The panels will be set back about 150 yards from the road, but because the land naturally slopes up from there, he says “they will be in plain sight of our front door and windows.” Leonard worries about the impact that may have on his property value, but also on the intangible value he has enjoyed from living across the street from a field where black angus have grazed, and from a wetlands that hosts migratory birds, owls, raptors, and wild turkeys.

While New York has its share of climate change deniers, the Copake residents arguing over Shepherd’s Run are not among them. Leaders on both sides of the controversy say they recognize the threat of climate change and acknowledge that if New York State is to meet its energy decarbonization goals, a lot more renewable energy infrastructure needs to be built—and soon.

But if what is playing out in Copake is any indication of what will transpire in other rural communities across the state, where large-scale solar developers are targeting sun-filled land tracts near transmission infrastructure, the state will have an uphill battle.

The Battle for Home Rule

New York State’s 2019 climate law, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, set ambitious goals for decarbonizing the power system. Under the law, the state seeks to get 70 percent of its power from zero-carbon renewables by 2030, and completely eliminate all fossil-fuel-generated electrical power by 2040.

To meet that goal, New York needs to build a lot of renewable energy. Right now, the state’s grid is only about 28 percent renewable-powered, most of which is from large hydropower plants. Another 21 percent comes from nuclear power plants. Utility-scale solar, wind, and biomass-generated power currently make up only about 6 percent of the energy produced in New York State.

Almost half of the electricity produced in New York comes from natural gas-fueled power plants. Many of them are located in densely populated lower-income Black and brown communities, where they cause higher rates of respiratory disease and premature death in surrounding neighborhoods. In order to meet the state’s zero-carbon power targets, all of those plants will need to be shut down and replaced by either renewables or nuclear energy by 2040. Meanwhile, demand for electrical power is expected to grow quickly with the electrification of vehicles and building heat.

If it seems like this is all happening with incredible speed, that’s because governments have delayed decarbonization for so long that swift action is becoming more urgent. An August report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, summarizing eight years’ worth of climate science, laid out the consensus among climate scientists in stark terms: Humans have warmed the planet about 1.1 degrees Celsius so far, and are already seeing the rapid acceleration of hurricanes, flooding, heat waves, and other extreme weather. If we hope to halt warming at 1.5 degrees—a level at which climate impacts will be more deadly and destructive—governments need to act to decarbonize in the next few decades. Failing to do so means locking in even greater, and more perilous, temperature increases.

In an effort to speed up the renewables buildout, the state legislature passed another law in 2020 to accelerate the review of solar and wind project applications. Under that law, renewable energy projects can opt out of the state’s lengthy Article 10 permitting process that normally applies to large energy projects, and choose instead to go through the state’s new fast-tracked Office of Renewable Energy Siting (ORES) process. Under ORES, all permitting decisions for projects over 25 megawatts must be made within one year of the project’s final application, with limited exceptions.

Hecate initially applied under Article 10 for its Shepherd’s Run permit. When the company opted to switch to the new accelerated ORES permitting process, Copake filed a lawsuit—not against Hecate, but against ORES and New York State, seeking to have all applications transferred back to the slower Article 10 process. Joining Copake as co-plaintiffs are a handful of other rural New York towns, some facing large wind projects in western New York, and a few environmental conservation and birdwatching groups.

The judge in the case has since denied the claimants’ request for a preliminary injunction and restraining order, which would have prevented ORES from granting permits until the lawsuit had been settled. Additionally, two amicus briefs have been filed in support of the state and ORES. The first was filed on August 31 by Scenic Hudson, the Sierra Club, NRDC, the League of Conservation Voters, and New Yorkers for Clean Power. The second was filed on September 24 by Friends of Columbia Solar, Friends of Flint Mine Solar, Win with South Fork Wind, and individual property owners and farmers who have signed leases, or plan to, with wind or solar developers in the state.

A key claim in the lawsuit is that ORES’s regulations were crafted in violation of New York State’s Environmental Quality Review Act, known as SEQR. State environmental law holds that if a state agency’s action may have a significant environmental impact, the agency must prepare an environmental impact statement. But the state adopted the regulations that govern ORES without issuing an environmental impact statement.

Towns like Copake have another fundamental concern: that ORES’s power to override local law presents a serious threat to a home rule tradition deeply rooted in New York’s rural governance. The powers of the Article 10 siting board to preempt local law have already stung a number of rural communities.

The state’s new fast-tracked renewables siting office says that it will “take local law into consideration,” and under the new process, municipalities must submit a statement about whether a project is in compliance with local law. But the new siting law allows ORES to overrule local laws that are “unreasonably burdensome” in light of the state’s ambitious renewable energy buildout goals.

So far, five utility-scale solar projects have been granted permits by the Article 10 board. Three of those decisions—in the towns of Sharon, Florida, and Coxsackie—were hotly contested by the municipalities because the siting violated their local laws. In each case, the board came down on the side of the developer, preempting the conflicting local zoning code provisions.

Fred Mauhs, an attorney who has advised on the siting of renewable projects in upstate New York, says it appears that ORES’s interpretation of the law requires the siting office to waive any local law that prevents the facility from being built substantially as the developer has proposed it. Under this interpretation, there’s little room for considering better alternative project sites. “If a developer has leased land for a solar facility in an area where it is not permitted by the local zoning code,” Mauhs says, “ORES will overrule the local law as ‘unreasonably burdensome’ to the project.”

That could hold even if the local zoning board identifies a better site for the project. Copake, however, has declined to offer an alternative location. “??We have told Hecate that the town will not come to them with a solution,” says Town Supervisor Mettler. “The burden is on Hecate to come to the town with a solution. To put the burden on the town to figure this out puts the town in the position of choosing one resident over another.”

Whether the fight was over wind, hydrofracking, solar power, or pipelines, rural towns have pushed back against state energy siting policy for years in an effort to preserve local decision-making power. But home rule has its own problems, energy experts say. “If approval of large projects goes through local decision-making processes, you are sometimes going to be pitting multinational companies against a volunteer board that will make one or two decisions like this in its lifetime,” says David Kay, a research economist at Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences who has worked with communities navigating energy transition and climate change.

Even smaller-scale projects often get bogged down in parochial concerns at the local level, says Kay, who has also served on local planning boards in the state. “If we have to get to a certain total megawatts fast, it’s unlikely that a sufficient number of small projects will move quickly enough through the local permitting process to achieve that goal.”

How Much Solar Should One Town Host?

Darin Johnson, a leader of Sensible Solar, the ad hoc group opposing Shepherd’s Run in Copake, proposes a third way for siting larger scale renewables: Figure out how much power each community needs to build. “The process has been fundamentally flawed from the beginning,” he says. “They put developers in the driver’s seat.” Johnson says the state should instead have developed a formula for what each county should contribute to renewable power, based on population and land size. “Each then could have undertaken a planning process, looked at land, and figured out the best places to put down solar.”

In their fight against the Shepherd’s Run project, Copake town leaders reference a specific statewide solar buildout target—6,000 megawatts by 2025—to argue that the town is being asked to build too much. “Given that we have 932 towns in New York, when Hecate proposes a 60-megawatt [project] in Copake, it is asking us to shoulder 10 times our share of new solar energy,” Town Supervisor Mettler says.

That 6,000-megawatt state target, however, was never meant to apply to large-scale projects like what Hecate is trying to build, but instead for smaller-scale “distributed” solar, which ranges from rooftop panels that power a single home to smaller community projects. That target is close to being met by existing and in-progress projects, and it’s already gotten an upgrade: On September 20, Governor Kathy Hochul announced that the state’s new goal for distributed solar buildout would be 10 gigawatts—equivalent to 10,000 megawatts—by 2030.

But the total figure for how much solar energy must be built to hit statewide goals in the next few decades is much higher. A 2020 study by the New York Independent Systems Operator found that in order to make the grid emissions-free by 2040, New York must build 39,262 megawatts of utility-scale solar power capacity along with large build outs of wind power. Energy developers will also need to build a lot of new power storage, based on batteries or other technology, in order to balance out power usage in a grid that will be mostly powered by variable sources like the sun and the wind.

And then there’s the inequity already baked into the system: Communities like Newburgh, home to an aging 511-megawatt gas-fueled power plant that owner Danskammer is seeking to rebuild, already shoulder more than their “fair” share of respiratory disease and death as a consequence of hosting fossil-fueled power plants in their backyards. The state’s climate targets aim to address those longstanding inequities as well as to decarbonize the power grid.

Copake’s solar zoning law limits the size of any single solar facility footprint to no more than 10 acres per parcel, in alignment with the spirit of the town’s comprehensive plan. At that size, the Shepherd’s Run project would be limited to 1 or 2 megawatts per parcel. Those who acknowledge the need for large-scale solar, like Friends of Columbia Solar, say Copake’s laws fail to fully reflect the current climate emergency.

Jen Metzger, a former state senator who now advises on policy for the nonprofit New Yorkers for Clean Power, says that communities need to face up to the hard math of climate adaptation. “We have essentially used up all of our slack, and have to achieve an enormous amount of change in how we generate energy in a very short period of time. It is simply impossible to get to our goals to prevent catastrophic warming without large-scale solutions.”

In a letter published in the Copake Connection, the town’s monthly online newsletter, Mettler expanded on the town’s main argument against the project: that it is too big for Copake and poorly sited. She also made an appeal that the current fight is bigger than Shepherd’s Run. It’s worth quoting at some length:

In this debate there are two sides. Both acknowledge the threat of climate change. We are suing NYS because ORES would allow a 245-acre industrial site in Copake without SEQRA review. The other side says “There’s a war on. We cannot worry about your viewsheds or local laws or SEQRA or home rule. Everyone has to do their part.”

This country has a long history of extreme measures because “there is a war on.” There was a war on and we thought it was okay to intern the Japanese. There was a war on Communism and we experienced the McCarthy era. There was a war on drugs and we passed the Rockefeller laws and locked up two-bit players for life.

We are suing New York State because NYS did not take the time and care to pass laws and regulations which would both allow renewable energy but also balance the very real concerns of rural communities like Copake.

There are two sides to the solar debate and both are correct. And someplace in the middle, there is a narrow strip of no man’s land where there could be compromise.

Alternative Solutions for Siting Large-Scale Renewables

The community pushback developers encounter often has a lot to do with how projects are initially sited. Typically, developers reach out to local governing boards only after they have identified a suitably sunny site near a transmission line or substation, and secured the required acreage from a willing lessor. “They put all the cake ingredients together and then ask the town, ‘How do you like this chocolate cake?’” says Samantha Levy, New York policy manager for American Farmland Trust, a farmland protection nonprofit. “Naturally, the town feels upset and disenfranchised.”

What’s more, if a town wants to propose a different site but the developer is unwilling to build the project there, the town can’t appeal to ORES for a resolution. “ORES does not give itself the authority to question the siting location, only to require mitigation of environmental harms on the site,” says Mauhs, the attorney. “So you might theoretically have a local zoning code that allows for a utility-scale solar facility anywhere except on prime soil. If, however, the company strikes a deal with a farmer to lease his or her prime soil land for a solar facility, ORES will only require the company to mitigate the impacts, not choose a different land to lease.”

Mauhs has an idea for revising the new renewables siting law so it is friendlier to towns: Only allow ORES to preempt local law if the zoning code in its entirety presents an unreasonable burden to the state’s achieving its renewable energy goals. That way, if an individual project violates local zoning code, but the code as a whole has room for large, viable solar projects, ORES would be required to respect home rule.

“Under this alternative permitting process, if a town’s zoning code permits ample siting of profitable utility-scale solar projects, but prohibits siting in environmentally sensitive areas or on prime agricultural soils, ORES would honor those prohibitions and not set them aside,” Mauhs says. He believes this interpretation would also encourage municipalities to develop renewables-friendly zoning codes, because they would be “preemption proof,” an incentive that neither past Article 10 siting decisions nor current ORES’s regulations create.

If they want more sway over siting decisions, Mauhs says towns need to strategize and negotiate. Simply saying “no” has not worked out for either municipalities or local activists. A better strategy might be to look for win-win compromises with the developers, where the community, local wildlife, and agriculture are protected, and the state also gets a significant contribution toward its renewable energy goals. “The siting authorities have consistently incorporated such amicable compromises into their final siting orders,” he says.

It might also be in the developer’s best interests to compromise. “Developing imaginative mitigation measures to reach an amicable settlement saves legal fees and valuable time in completing a project,” Mauhs says. “Plus, simply building a reputation as a good neighbor goes a long way with rural New Yorkers.”

Towns looking to be proactive on solar siting have some resources to turn to, at least in the Hudson Valley. Scenic Hudson is working with municipalities on climate and resilience issues, and has an online solar siting tool that can be used to identify possible locations for larger projects.

Can Dual Use Be a Win-Win for Agriculture and Renewables?

Preserving farmland and addressing climate change are important—if sometimes conflicting—environmental goals in New York.

Levy says that American Farmland Trust has experienced all the stages of grief as it contemplates the inevitable impact that large-scale solar will have on the state’s farmland. Developers’ requirements for access to transmission lines and roads, willing lessors, and lots of sunlight represents “a perfect cocktail of factors” for New York State farmland conversion to an industrial use, she says.

“We know climate change is real and happening, and we need to mitigate it to survive as a species and continue to farm. But at the same time, we can’t just use that as a reason to make thoughtless choices. With the state pushing large-scale renewables siting in a market-based way, they are in effect pushing development to our sunny farmland fields, our most cultivable acres.”

Levy says that in an ideal world, utility-scale projects would be banned from prime farmland. “Why are we developing prime first when we have all this marginal land and such a small percent of farmland that is prime?” she asks. “Why can’t we apply a little planning and develop policies to re-site those projects to marginal land, where we don’t push our food production into areas that are more environmentally sensitive or less economically viable?”

The River reached out to NYSERDA and ORES to ask how the new permitting process will effectively discourage developers from siting facilities on prime soils or of statewide importance. In an emailed statement, NYSERDA spokesperson Claudette Thornton said that NYSERDA and the state Department of Agriculture and Markets have mapped the approximate locations of those soils, and that developers may be required to pay into an agriculture mitigation fund based on the extent to which their final project’s footprint overlaps with them.

But ORES takes the view that the impacts of solar projects on farmland are negligible, since the land can theoretically be returned to productive use after projects are decommissioned. “ORES does not find that the major renewable energy facilities will have a significant negative impact on the statewide agricultural community, given the minimal permanent conversion of agricultural lands,” says spokesperson Nathan Stone.

The state’s mitigation fund is due to be established in 2023. American Farmland Trust is hoping that ORES can be persuaded to use it to offer developers incentives to incorporate agricultural uses into site plans. Massachusetts, for example, has created innovative dual-use incentives that permit solar developers to charge as much as an additional 6 cents per kilowatt hour to ratepayers if their plans fully integrate agricultural uses and pass muster with Ag and Markets. The guaranteed premium enables the developer to access private financing to defray infrastructure costs and to justly compensate farmer partners, says Drew Pierson, head of sustainability at Blue Wave Solar, which has two dual-use projects in the pipeline in Massachusetts. A similar incentive plan was recently passed in New Jersey.

Here in New York, projects that combine farming and energy production have so far been mostly confined to solar pasturing. Since 2019, Erica Frenay, whose family owns Shelterbelt Farm in the Finger Lakes region, has been leasing about 100 of her flock of 140 sheep to Agrivoltaic Solutions LLC, a company that provides grazing services to solar farms. So far it has been a winning arrangement for her farm business, Frenay says: The grazing service manages her leased flock, her cost to lease land for pasturing is less than it would otherwise be, and she gets paid for each day her sheep graze on a solar facility.

“The sheep come back to me fat and happy and I stockpile forage for them on my farm for their return,” she says. Meanwhile, the sheep that remain on her pastures have more room to graze, while the others are out on lease on solar fields. “If I were paying for that additional grazing land, I would probably be paying over $1,000 annually for it,” she says. “Instead, I get paid several thousand dollars to lease my sheep out.”

While Frenay supports solar grazing on land that would otherwise not be productive cropland, she urges solar companies not to site solar on prime farmland. But she sees solar pasturing as a way to diffuse the tensions between farmland and renewable energy advocates. She also believes solar grazing services represent a promising new career pathway for farmers and others. “The solar companies typically would otherwise work with a landscaping service that comes in with lawn mowers and weed whackers to manage the areas around the panels,” she says. “But if you can have the sheep do the work of the fossil-fuel-powered mowers, and the economics are favorable, it's a win-win for farmers, solar developers, and communities.”

Metzger believes New York should take a more active approach by reaching out to potential farmer-partners to identify appropriate sites for dual-use development. “I have a real appreciation for how many farmers are struggling to survive,” she says. “The state should be seeking out those situations where a farmer can co-locate on land. This requires identifying all of these local possibilities for win-win solutions for ag and energy, but also areas that are of least conflict for communities for renewables development.”

Although Hecate has no track record with dual-use development (also known as agrivoltaics), Alex Campbell, project director at Shepherd’s Run, says that he is in talks with solar pasturers, pollinator meadow experts, and apiary operators as potential partners. He points out that if the Hecate project moves forward with these partnerships, the farmland where Shepherd’s Run would be sited will actually be improved, since it is currently monocropped with the application of chemical fertilizer. “If someone wants to talk to me about shade cropping or other regenerative agriculture practices as well, I am all for it,” he says.

Meanwhile, some in town are skeptical. “Everyone in Copake loves to see sheep, and we are all in favor of pollinators,” says Mettler. “But most people who have heard Hecate’s promises see it as just camouflage or window dressing.”

What Comes Next?

The distrust and polarization around Shepherd’s Run illustrate how hard it is to get renewable buildout right. “This isn’t an easy place to be,” says Audrey Friedrichsen, a land use attorney for Scenic Hudson, on the challenges of solar siting. “We all want to make this energy transition happen and everyone wants to get to a good place with this.”

Local opponents of Shepherd’s Run accept that solar will play a significant role in Copake’s future. “Solar is not going away, but whatever gets built in Copake will be with us for decades,” says Johnson of Sensible Solar. “What we said to the governor’s office is, ‘Use Copake as a pilot.’ This is an opportunity to figure out how towns and developers can resolve their differences.”

Despite her concerns about how farmland will be impacted by utility-scale solar in New York’s rural communities, Levy hopes that “if people can band together and have good conversations about mitigation—not just to stop a renewables project—then maybe at the end of the day folks can feel some sense of pride in having done their part to mitigate climate change. That may be the ultimate silver lining.” She adds that we also need to acknowledge that marginalized communities in New York were powerless for decades to stop fossil-fuel plants from being sited in their backyards. Acknowledging the state’s legacy of environmental injustice might motivate everyone to find equitable ways to site renewables.

Mauhs also sounds a cautiously optimistic note about the future of energy siting in New York. “With so much attention and money aimed at the state’s rural land, communities have an opportunity to get developers to commit to real conservation measures in exchange for siting,” he says. “The current siting controversies have the benefit of focusing our minds like never before on just how valuable New York’s land and natural resources are.”

Read some responses to this article in our Opinion section:

- How Language Is Shaping the Solar Energy Debate, by Dan Haas of Friends of Columbia Solar

- Why the Town of Copake Opposes Shepherd’s Run, by Town Supervisor Jeanne Mettler