You're driving up a dirt road across farmland on a cold Dutchess County afternoon. After admiring the orchards and open fields for several minutes, you park next to a long, low, brightly painted stone-block outbuilding, a structure that you later learn was originally built as a piggery, and then step out of the car. Having dashed through a passing flurry, you're soon knocking at the back door.

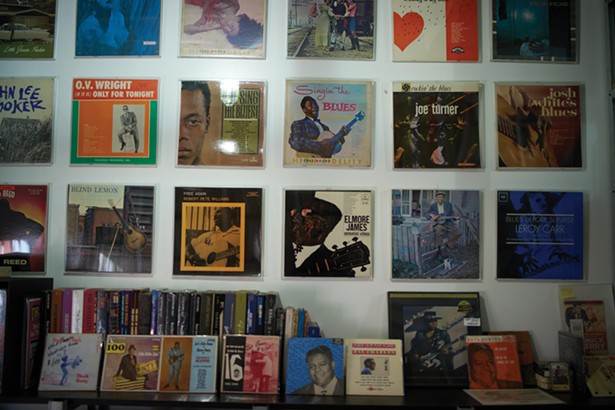

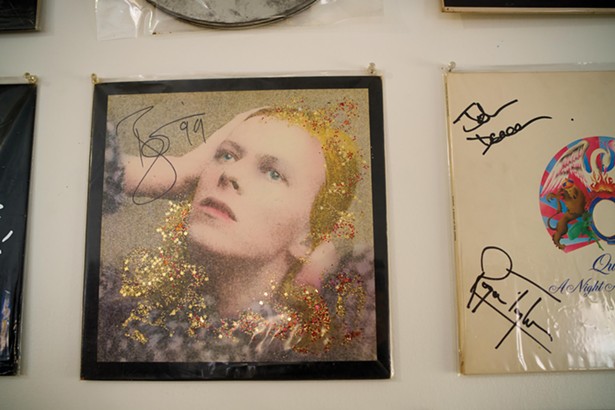

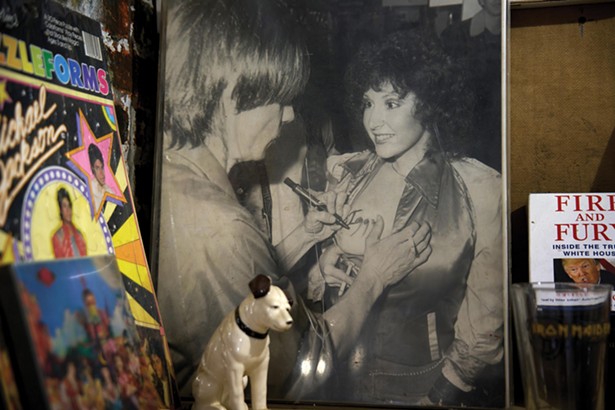

Inside, it's a pharaoh's tomb for music fanatics. Chest-high, labyrinthine stacks of cartons filled with LPs take up the entire floor of the room, and the walls are lined with floor-to-ceiling industrial shelves filled with more LPs and white cardboard boxes of seven-inch 45s. In the next room of the sprawling interior, it's even more of the same, along with crates, shelves, and boxes of 10-inch 78s, cassette tapes, CDs, and music-related books, DVDs, VHS tapes, and ephemera (photographs, periodicals, press kits, sheet music, T-shirts, promotional items, memorabilia), and the walls are adorned with framed posters and album covers, many of them signed by the likes of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Queen, David Bowie, Jimi Hendrix, the Sex Pistols, and other luminaries.

In the other rooms, it's the same story, seemingly going on forever. A short walk away is a giant former cow barn whose first floor is packed solid with pallets of records and other materials, all of the items representing every style of music from around the world. Welcome to the ARChive of Contemporary Music.

In total, the ARChive's two-structure facility in Staatsburg—called the Arc by its staff—occupies 10,000 square feet, and there are spaces in California totaling 3,000 square feet. At this point, the organization has collected and cataloged over three million sound recordings containing more than 100 million songs. And that number is growing, each and every day, through estate donations and other acquisitions. But now the Arc has to move. And at present it has nowhere to go.

"The buildings we're in are still zoned agricultural, which we didn't know would be a problem when we relocated here," explains Bob George, the ARChive's cofounder and director, about the property, whose usage was donated by its owner, luxury hotelier Andre Balazs. "We had to get out of our original space and Andre very generously offered to let us move here, so we jumped on it. But it turns out that because of the zoning designation we can't get the required permits to be able to install enough shelving and the other amenities we need. And in the meantime, most of the collection is just sitting here on pallets, inaccessible and in danger of deteriorating." Hence the desperate hunt for new digs for the nonprofit.

Pump Up the Volume

Interested in art from an early age, George grew up in Youngstown, Ohio, and spent much of his 20s traveling, soaking up the cultures in regions like Afghanistan, Russia, Sweden, Ukraine, and India, where he briefly had a job preparing corpses for ritual cremation. He came to Manhattan in 1974 to study in the Whitney Museum studio program. While at the Whitney he befriended another young creative mind: Laurie Anderson, whose first commercially available recordings would appear on Airwaves, a 1977 experimental music compilation album on the label he launched to release it, One Ten Records. A record obsessive in the thick of the punk/new wave explosion, George coauthored 1980's Volume, the first comprehensive discography of the new music. In the pre-internet days, the book served as an essential reference for those who were following the frenetic output of the DIY-driven movement.

After corresponding with the influential British DJ John Peel, George became a frequent guest on his BBC show, always bringing along the latest US underground records; one such item was Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five's formative 1982 hip-hop milestone "The Message," which sent shock waves through the UK music scene. In 1981, One Ten released Anderson's debut single, the game-changingly abstract "O Superman," which, thanks in part to Peel's championing of the track, was a surprise number two hit in England and cemented her worldwide status.

In 1985, George and his late collaborator David Wheeler established the ARChive of Contemporary Music in a Tribeca loft with a lofty goal: To create an eternal repository of modern music by acquiring and preserving a copy of every known popular music recording made by every culture and race in the world, in every format it was manufactured in. "I'd built this huge personal collection and I wanted to keep it together for future generations, but no other institutions wanted it," he explains. "You had places that collected older ethnic music or classical music, or the Smithsonian Institution, which was more interested in folk music. But they weren't looking for the kind of stuff we have, which includes funk, hip-hop, reggae, contemporary African music, and rock 'n' roll. So we decided to do it ourselves and build on what we already had."

Critical Mass

George, who claims not to own a single record himself nowadays—he started the ARChive by donating his own collection of 47,000 discs to the foundation—began reaching out to music-industry friends and to the public about deeding the records and related materials they'd amassed to the effort and monetarily supporting its collection's storage and maintenance. Among the names on the ARChive's advisory and emeritus boards are David Bowie, Todd Rundgren, Martin Scorsese, Paul Simon, Lou Reed, David Byrne, Nile Rogers, Courtney Love Cobain, Q-Tip, Carl Bernstein, Jonathan Demme, and Keith Richards, who directly backs its blues library and even gifted it a rare original copy of Robert Johnson's 1937 "Me and the Devil Blues."

Another board member and booster is the B-52s' Fred Schneider, who has DJed and performed at ARChive-sponsored events. "The ARChive is a sort of Noah's Ark of music to me," says the singer via email. "You're not gonna get 95 percent of any of what they have in the ARChive on the streaming services, which sound like crap anyway. I'm so happy to have been a part of it."

As it continued to acquire important collections—for example, that of 1960s/1970s Michigan music scene figure Jeep Holland, whose collection was so voluminous that it was literally causing his house to sink—the ARChive was steadily outgrowing its Manhattan space. On top of that, by 2020 the rent in the once-destitute, now-tony Tribeca neighborhood had gone stratospheric. Thus, one $60,000 moving invoice later, the ARChive's East Coast holdings were in Staatsburg. And at present, four years later, the organization, which subsists partially by providing archival images and recordings to publishers and movies—for example, George recalls how director Ang Lee came calling for songs by obscure folksinger Bert Sommer to use in his 2009 film Taking Woodstock—is looking at another massive move.

Gimme Shelter

It's hard not to think of the ARChive's priceless riches and not recall the 2008 Universal Studios fire that destroyed thousands of original master recordings—masters being the equivalent of the Mona Lisa that hangs in the Louvre to its souvenir-shop repros—of irreplaceable works by Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, Bing Crosby, Muddy Waters, and other giants. While the ARChive doesn't concentrate on masters, its expertly collected, sorted, and cared-for artifacts provide a vital contextual window into the eras they emanate from.Although the Arc hasn't been open to the public, George's vision for its new home adds a public component, with space for live music, DJ dances, talks, and other happenings as well as a wing for scholarly research access. Partnering with a university is one idea, and there's been some discussion with Bard College about collaborating on a property. Another angle could involve a culturally conscious donor helping the foundation purchase vacant land and build a new center on it, or to acquire and convert a former IBM campus in Poughkeepsie. In the interim, though, George and his staff expect to begin packing up on February 14.

So with the advent of digital media, why hold onto and move all of this stuff? Schneider's comments about the scarcity and sonic superiority of the items collected by the ARChive aside, there's George's succinct answer. "A lot of what exists only online is going to go away someday," he says, adding that as backups to the original pressings it has, the ARChive recently digitized its 106,705th seven-inch 45-rpm single and has done the same with over 370,000 78s for the San Francisco-based Internet Archive. "The majority of what's only commercially available is going to disappear. For over 1,000 years, people in Europe had forgotten how to build domes, until Brunelleschi studied how the Pantheon was built and based his design of the Florence Cathedral on it. To really understand the music and times of the past, it's important that people in the future be able to access and understand that music in the way it was heard by the people of the past. Physical things last."