Nature's abundance is mind boggling," says author and designer Susanne Meyer-Fitzsimmons. "Look at an apple tree—one tree produces hundreds of apples, and each apple has a handful of seeds out of which can grow thousands more apples." We are sitting in the living room of the contemporary, passive solar-hybrid house that she shares with her husband, Brian Fitzsimmons, and their two teenaged children. She is explaining the research and philosophy that inspired both her home's design and her forthcoming book, Deep Living: Healing Yourself to Heal the Planet (Full Court Press), which is out this month.

"It's a quandary of our culture—we've created an economics of scarcity where we always feel guilty about using or doing or making when in reality, that's often in our thinking. Our economic paradigm, which is built on credit and borrowing from the future, also makes us believe that there's never enough." On one hand Deep Living is an exploration of the philosophy of sustainability and the cultural choices that have led us to our current environmental crisis; on the other, it's also an invitation to reexamine our values and reimagine how they can be reflected in our daily lives. "We need to get off the hamster wheel," Meyer-Fitzsimmons declares. "Then we can really ask ourselves 'What do I stand for?' We've lost our connection with the Earth and with other people. But in reality those are the things that make us happiest: We need community, we need other people in our lives, we need nature."

Philosophy of Light and Space

Everything about the room we are sitting in echoes Meyer-Fitzsimmons's ideals. The mid-January sun floods the space with light, spilling across the Auburn wood floorboards, illuminating the open-plan dining and sitting areas, and reaching back into an adjacent kitchen. Twenty-foot ceilings add to the living room's airy, expansive atmosphere of abundant light and space. Oriented to the south and perfectly calibrated to accommodate the seasonally changing arc of the sun, the room's southern wall is a combination of sliding glass doors topped by rows of windows of triple-paned glass. To the east, a wall of white, built in bookshelves—is topped with another bank of windows, this one calibrated to catch the morning sun in the summer months. Louvered panels, hanging over the south-facing windows, are angled to block the midday sun in June, July and August. This, along with the home's metal siding and roof, allows the structure to remain remarkably cool in the summer months.

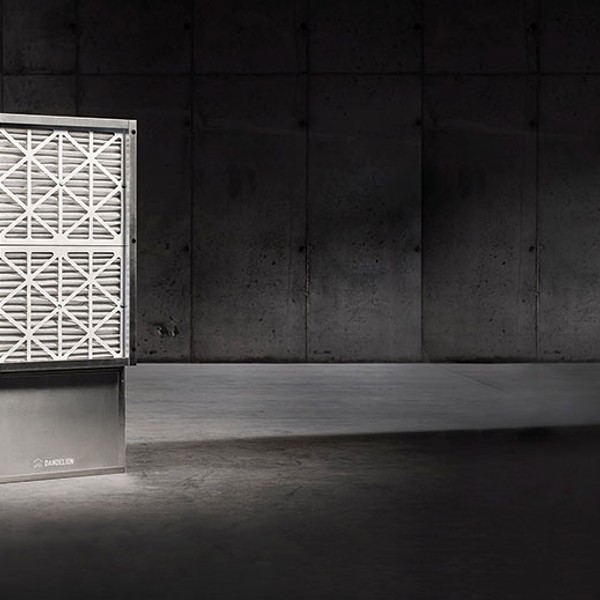

But now, as we sit enjoying homemade artichoke spread and spinach pie, the room is cozy and warm. "The thermostat is set to 68, but often when it's 20 degrees outside and sunny, the thermostat rises to 72 or 73 degrees," Meyer-Fitzsimmons explains. This seemingly effortless comfort is achieved through a harmonious hybrid of cutting-edge technology and sustainable construction methods. The home's passive solar architecture is complemented by 10-inch-thick open-cell, foam-insulated walls. At night LED track lighting consumes a fraction of the energy incandescent or even compact florescent bulbs would. Three photovoltaic solar panels on the roof provide for the majority of the home's energy needs, as well as power a geothermal pump and furnace to heat and cool the home. At the end of the solar year—March 21—the house has broken even, energy-wise, and effectively has a "net zero" carbon footprint since May 2016.

Free Associative Design

Originally from Berlin, Meyer-Fitzsimmons spent much of her childhood in France and then began college in Belgium. However, after two years of studying interior design there, she was finished with European university life. "I was so sick of the system—it was too hierarchical and restrictive. I was under the impression that art should teach you to be creative, whether its fine arts or the decorative ones." She had a deep desire to "free associate and be creative—not to regurgitate." "I had to get out of there," she explains. So she took a chance and picked up for New York where she finished her bachelor's degree. "College education is more liberated here, it makes you a freer thinker," she says. Eventually Meyer-Fitzsimmons began a master's degree in Liberal Studies at Empire State College and the research and writing of her master's thesis became the basis for Deep Living. She met her husband, Brian Fitzsimmons, in New York and, after a stint in Hong Kong, the couple moved to Warwick in 1993. They and their two young children lived for many years in a 200-year-old house that was so drafty "the weather came with you whenever you opened a door—we were definitely close to nature."

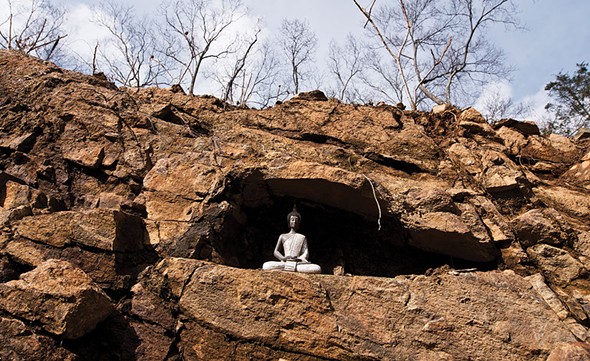

In 2005 Fitzsimmons stumbled onto an eight-acre parcel of land, with a For Sale sign, right around the corner from their former house. With a protected ridge line at the back of the property and a view over the woods toward Bellvale Mountain, the couple realized it would be the ideal place to build a home based on their shared environmental values. They purchased the land, took some time to pay it off, and then began the three-year planning process that would result in their current abode. "It was a very creative, complex effort," Meyer-Fitzsimmons explains. Brian Fitzsimmons, a manufacturers' representative for lighting and energy controls, did all of the mechanical research. Meyer-Fitzsimmons roughed out the design concept and then architect Jeff DeGraw, of DeGraw & DeHaan, pulled it all together. The actual construction took 14 months and was completed by Kevin Gremli Construction in August of 2014.

Beyond the Great Indoors

The 2,900-square-foot house was designed to be a combination of three "bubbles"—a section for the couple's two teenaged children, a master bedroom wing for the adults, and the central community space shared by family and guests alike. "Because I have a design background and because we lived for 20 years in a space that didn't shift and move with us, I had the opportunity to rethink the whole way we interact with our living space." The children's rooms mirror each other and are separated by deep closets that allow for both acoustical privacy and clutter control. ("I told the architect the rooms had to be the exact same size," she tells me.) Large south-facing windows lend a light, airy feeling similar to the main living space, making each bedroom seem much larger than their 110 square feet. The family loves to entertain, so a large kitchen pantry was designed to store multiple folding chairs. Now, dinner parties can easily accommodate one or two extra guests at a moment's notice.

The home's master wing, built in the sunny eastern end of the house, has a full bathroom and walk-in closet, as well as two home offices. Meyer-Fitzsimmons's north-facing desk overlooks the wooded ridge line where she occasionally sees foxes, bears and deer. The ground floor basement has a garage, a recreation room, and a large laundry area—inspired by the German washkuche ("wash kitchen") of Meyer-Fitzsimmon's homeland—with plenty of space to line dry clothing, even in the winter months.

Even though technology has allowed the home to be "heavenly comfortable" while keeping its carbon footprint light, Meyer-Fitzsimmons understands that even technological advancement has its limits. The family is mindful not to let its use dominate their shared space—relegating the home's only television to a shared den/guest room and computers to their respective workspaces. Without a television or computer in the main living room, the ever-changing view of the woods becomes the room's focal point and the quiet encourages conversation. This was a lesson in mindfulness Meyer-Fitzsimmons learned from a friend of her son. "When Hurricane Sandy hit, we were out of electricity for days," she says. "My son's friend pointed out that while we had no power, friends—adults and kids, family, and neighbors—were sitting around the table playing board games or just talking." We were always doing things together. The minute the power came back on, everyone retreated to their electronic devices. For a brief amount of time we had no electricity, but we rediscovered our community."