The sleeve tattoo on David Carrell's right arm tells the story of the last dozen years of his life. On his elbow, there's a tank sprocket—for the vehicles he commanded during his four combat tours in Iraq as a staff sergeant in the Army. Around it are inked the initials of the 17 soldiers from his company that were killed over there. (Carrell needs to add two more, for comrades who committed suicide after coming home.) A skull with two sabers crossed up behind it represents the cavalry unit he deployed with. And there are the combat stripes, eight in all, one for every six months he spent in Iraq.

Carrell is a solid man with tightly-cropped blond hair and a heavy Texan drawl. When we meet in a Starbucks on Route 9 just south of Poughkeepsie, he's just come from his post-traumatic stress disorder therapy. He has nightmares. He has flashbacks. He ruminates and processes the things he's seen—the death and destruction and despair. "You just can't forget it," he says. "Before my feet hit the ground in the morning, I think about the war five times. While I'm brushing my teeth, that's what I think of. It's like having a movie in your head that's always on. If you don't keep yourself busy, it'll eat you alive." So he keeps busy. With the therapy, with a peer-to-peer veterans' counseling support group. With Operation Veteran Admission—but we'll get to that.

War will mark a person. But a particularly steep toll has been paid by the 2.6 million Americans who have served in Afghanistan and Iraq, the first major American wars fought by an all-volunteer army—and the longest and third-longest in the nation's history, respectively. These men and women took part in nasty conflicts, against insurgencies fighting with IEDs and suicide bombers. They came home with unprecedented cases of PTSD and addictions to a cocktail of psychotropic meds, reportedly misused by the armed forces to allow troubled soldiers to function in the battlefield. The shock from the explosions left them with traumatic brain injuries; the shrapnel with disfigured bodies. Some experienced sexual violence within the military. Almost all returned to a nation that said it was grateful but did little to back up its lip service. More than two million Americans came home to a wretched economy, soaring unemployment, a VA with year-long wait times for treatment and benefits, retirement payments that lagged many months behind. Veterans fell into homelessness.

Gradually, suicide grew rampant among them—a VA study found that male veterans under 30 are much more likely to take their own lives than the regular population. Their homecoming was disappointing. Their bodies were broken and their minds still at war. Finding a new way to be productive is key, but for many, that was and is an elusive goal.

Keeping Busy

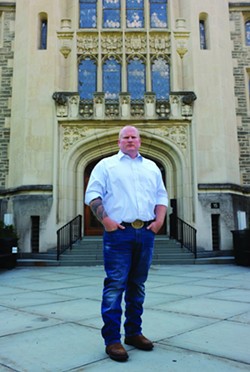

Carrell has been busy though. When we meet, the thing that's consuming him is the paper on Nazi propaganda that's due later that day. At 34, Carrell, a husband, father of two teenagers and owner of two dogs, three cats, five fish, and hamsters of a quantity he can't remember right now, is a junior at Vassar College after 11½ years in the army. He's a history major with a full course load. He spent 14 hours in the library yesterday, until very late, and he will be there longer when finals roll around. Luckily, the lady who runs the library lets him in early many days, before it opens at 8am. When we finish talking, he'll go back and work on another paper.

This isn't how Carrell had imagined his life would go. He always figured he'd make the army his career, putting in the two decades required for a full pension. And certainly, after completing a 9-month, a 15-month, and two 12-month tours in Iraq, he'd proved his worth. There are easy deployments and there are hard ones. Some soldiers spend the entirety of their time in the theater of operations inside the various compounds, working a desk or logistical job, far from the action. Not Carrell. He was in Balad, Baghdad, Mosul, and Najaf, patrolling hard-fought neighborhoods, swerving the tank around the IED craters left when his peers and friends had been blown up. In some 1,100 tank missions, driving around in a big freaking target, he figures he made contact with the enemy at least 300 times. Sometimes every day for two straight months. The longest he went without getting shot at, he reckons, was 10 days. He spent four years of his life living in perpetual stress, playing Russian roulette every time the tracks rumbled out of the compound gates.