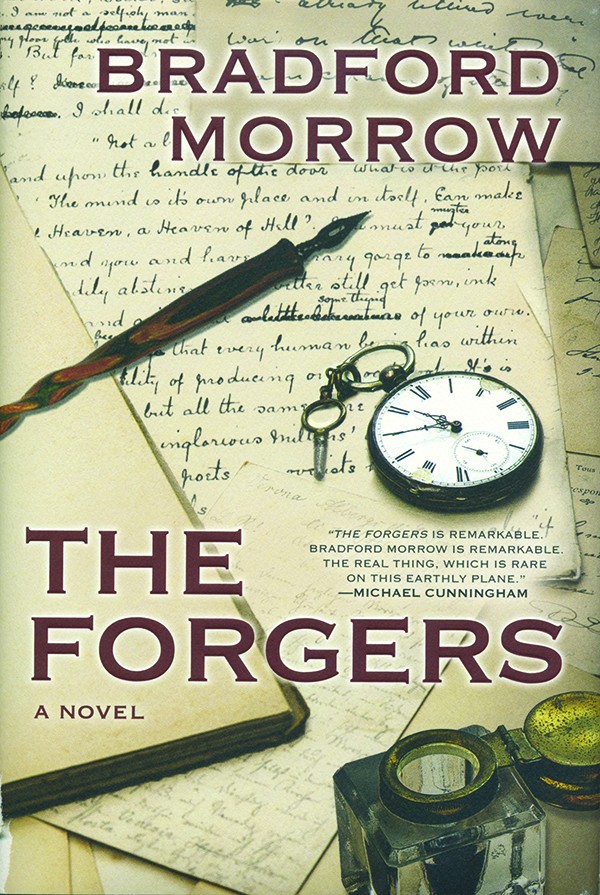

The Forgers, a beguiling new crime novel by Bard Center Fellow Bradford Morrow, ushers readers into a world of rare holographic manuscripts where obsessed bibliophiles seemingly stop at nothing for a fix. The book opens with a murder, the victim's hands excised and notably missing—as if they had "become a pair of wings, and flown away across the gray Atlantic." Although Morrow's narrator, a one-time convicted forger with a specialty in "Conan Doyle and Sherlockiana," is not above suspicion in the unsolved case, the whimsy in his tone combined with an unpretentious air of connoisseurship have the effect of exculpating him somewhat. The question of his involvement in the brutal deed is nevertheless disquieting, and it presses on the reader with a Moriarty-like persistence.

In the acknowledgments, Morrow tells of his experience in the antiquarian book trade and attests to the high-mindedness of book dealers he has known. The disclaimer strikes us as necessary. In the age of social media, the solitary hours spent by bookish types might well be perceived as corrupting or alienating, even by those who are themselves addicted to the printed word. One is reminded of Arturo Perez-Reverte's 1993 biblio-detective classic El Club Dumas, which takes measure of the reduced social relevance of literature, and makes the tradition's remnants into a bastion for deadly occultists.

Not inspired by demons, or even money, Morrow's forger is an oddity among criminals. Beneath his educated ease, he struggles with the temptation to duplicate the cursive quirks of great writers. He got hooked young, "when I lowered my nib to the virgin paper was the most erotic feeling I could possibly imagine." Now a father-to-be with an itch, he is pressured both from inside and out to resume the game: "The sirens might be singing to layer in another fine cliché, but I knew their song by heart and kept their invitation at bay." His literate quips, often limp as a Nereid's tendrils, give indication of his hand-tied state. It dawns on us that what most people find valuable in books is not really so important to him, even though he has the ability to tell by a turn of phrase if a note attributed to Henry James is authentic or not.

When he receives a spuriously autographed volume of Yeats, a disturbing gift from a less talented forger, one meant to shake him up, he does not recognize the very famous "dancer from the dance" verse used in the bogus inscription. Though unsettling, the gap in knowledge is understandable, not criminal. His is a visual enterprise, what matters are "the nuances of calligraphic art, a refined sense of historical materials, the science of empathy." For this character, the difference between William Faulkner and Tarzan author Edgar Rice Burroughs boils down to the fact that Faulkner is easier to copy.

There is a gleam in this storyteller's voice—less than victorious, but a shade above mere contentment—as he imparts the lessons of his art. We are told the British Parliament debated making forgery a capital crime in the 19th century, and are encouraged to weigh the case ourselves. His muffled regrets, the shame that would have fallen on his book-loving parents were they alive, the strained acceptance of his tarnished integrity—the psyche of a con artist is terrain in which Morrow excels.

—Marx Dorrity