It's impossible to meet Eamon Grennan without knowing at once where he's from. His musical lilt, wild thicket of eyebrow, and affable smile are every bit as Irish as his name. So it's a bit startling to hear that the Dublin-born poet has identity issues.

The Vassar professor emeritus and author of Out of Sight: New & Selected Poems (Graywolf Press, 2010) has lived in the US since 1965, when he became a graduate student at Harvard, but has never sought citizenship. "I'm a resident alien—like every poet, I suppose," he says with relish. Perceived as an Irishman in Poughkeepsie and an expatriate in Ireland, Grennan describes himself as "neither here nor there—or rather, here and there.

"One of the things I was working toward with Out of Sight was that doubleness as the dominant feature," he attests. "I'm seen as an Irish poet who writes American poetry, or an American poet inflected with Irishness—as a poet of both places."

Indeed. Grennan's poetry flows like a body of water between native and adopted shores; it's no accident that Out of Sight begins and ends at the liminal edge of the ocean, where shorebirds skitter and tides perform their daily cycles. The book's first line is "I would like to let things be"; the last is "the jag-line leading from this to that, before you turn for home." In between are two decades of work that amount to an autobiography of sight and reflection.

Plainspoken and richly evocative, Grennan's poems are filled with birds, plants, and water, with windows and light—the natural world and the means by which we perceive it. "There are not a lot of people in my poems," he remarks a bit ruefully, but there's one who is present in every line: the poet himself, as a preternaturally sharp-eyed, full-hearted observer of life in its glorious, aching detail. Former US Poet Laureate Billy Collins has written, "Few poets are as generous as Eamon Grennan in the sheer volume of delight his poems convey, and fewer still are as attentive to the available marvels of the earth."

The surface narrative of a Grennan poem is often an everyday moment—a bee becomes trapped behind window glass, a garbage collector upturns shining cans, a father watches his son embark on a train—that illuminates emotional truths lurking just out of sight. "I'm struck sharp as a heart pain/ by the way this minute brims/ with the whole story," he writes in "Two Climbing."

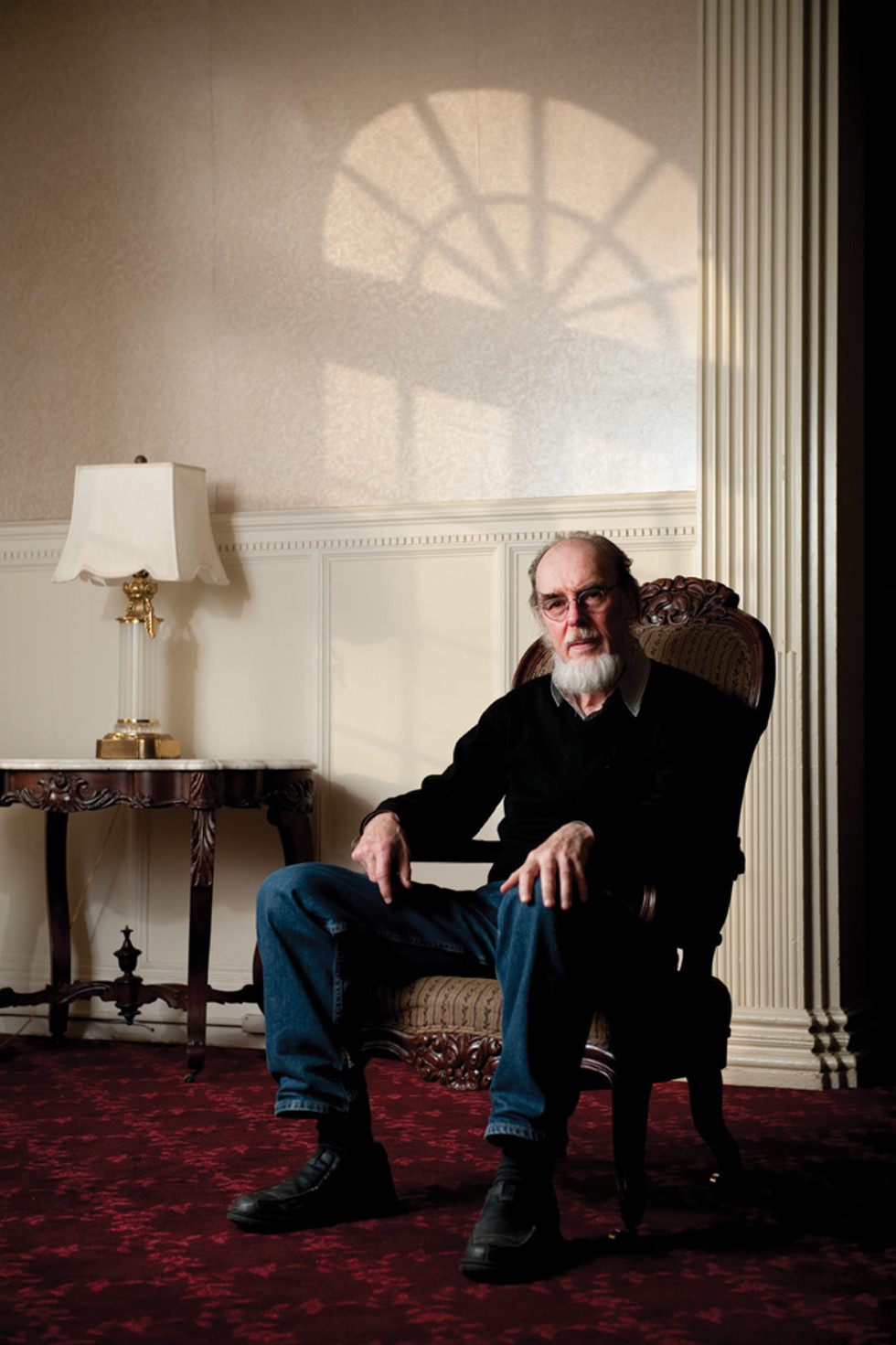

Perched on a Victorian chaise in Vassar's Rose Parlor, Grennan sports a black sweater, jeans, and a bristling white beard that gives him the air of an uncommonly friendly Mennonite elder. His sentences unspool like great skeins of yarn, winding around and around, adding texture and warmth as he searches for just the right image. He frequently asks, "D'you know what I mean?" or "Is this making sense?"

Along with 30 new poems, Out of Sight includes poems culled from seven previous books. The winnowing process was difficult. "You always feel, 'I'm rejecting these,' as if they were your children," says Grennan. "You choose poems because you feel they still work, that have an organic body, that feel musically like there's a bit of lift, that engage with the world in a way that feels honest. Every poet is a reader first—your reading preceded your writing."

He started reading poetry as a teenager at an Irish boarding school run by Cistercian monks. As a "city boy planted in the middle of the country," discovering Wordsworth and Longfellow helped assuage his loneliness. At Dublin's University College, Grennan wrote poems and stories, joined the drama society, edited a magazine, and hung out in pubs—"what one does as a lively young literary creature." Then he spent a year living in Rome, where he met his first wife, Joan Perkins. (He's been married to Vassar classicist Rachel Kitzinger for the past 25 years.)

Grennan arrived at Vassar in 1974 with his wife and two stepsons, one young baby, and another on the way. Though his specialty was Shakespeare and Renaissance literature, he also taught poetry. Most of his writing was "scholarly stuff, because one had to earn tenure." But he also started to write poems again, and finally took a year off, bringing his family to Ireland. "I went back to write and hook up with my Irishness, but I brought back a sack of American poetry books," he says with a laugh; he has cited Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Frost, William Carlos Williams, and numerous others as inspirations.