In the liner notes to Red Morocco, the 2007 release by saxophonist and composer Joe Giardullo’s Open Ensemble on France’s RogueArt label, jazz authority John Szwed describes the session: “The results are elegant, shimmering, ringing music, like colors spiking across the plane of a Monet canvas, or spinning like a piece of Calder’s kinetic art; a constantly moving, deeply sonic performance, collectively improvised, and decentered; a self-organizing musical system, with minimal input or constraints from outside. Giardullo is willing into existence a music that occurs beyond his control.” Szwed, who has authored award-winning books on Sun Ra, Miles Davis, and Jelly Roll Morton, is grappling with what Giardullo calls his G2 Music, or Gravity 2 Music; an updated version of the compositional approach he developed in the mid 1970s, then known simply as Gravity Music. But what, exactly, is all this Gravity business about, and what’s the difference between the old and new models?

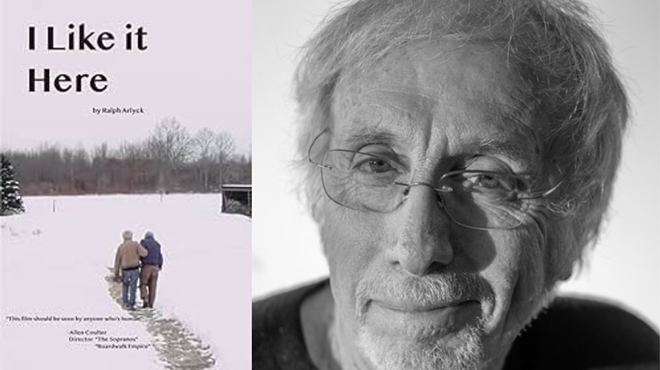

Leaning into his latte in a Kingston coffeehouse, the white-bearded Giardullo, attempts an explanation. “Most Western music is based on functional harmony,” he offers. “That is, it’s the harmony that moves the material, the chords that dictate the movement. Which is fine, but I don’t find that very interesting. Gravity [Music] is about not making any one particular aspect of the music more important than the others; it’s about having no solos and being omniharmonic, of giving equal weight to every pitch, every note. To play it correctly, you really have to leave your ego out of it—in fact, [Down Beat critic] Francis Davis said my first record [1979’s Gravity] was the most democratic music there was. The reason I call the method I use now Gravity 2 is because during the first period I was doing all of this without really understanding what it was that I was doing. Now I see more how it works, and that affects the music. So I wanted to make a distinction. It was just something I had to go through to get to this point.”

There were, of course, other things the Cottekill resident went through before he arrived at his current spot in the avant-jazz firmament. Giardullo, a primarily self-taught soprano specialist who also plays tenor, sopranino, flute, and bass clarinet, was born in Brooklyn in 1948 and at the age of seven moved to Long Island, where he discovered rhythm and blues. “I was part of a clique that was really into that stuff before it crossed over into the pop charts,” he recalls. “James Brown, The Falcons with Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave—all of those guys.” By the time he was 14, Giardullo was playing with R&B bands up down the East Coast on weekends. “My folks were cool with it, as long as I kept my grades up and didn’t get into trouble,” he says. “It was an easy deal for me. And until I got into college, I thought R&B was the be-all and end-all.”

College was SUNY New Paltz, a school that Giardullo selected at random. Or maybe it selected him. “I had qualified for a scholarship to the state college of my choice, and I just blindly picked it out of the guidebook,” he says. “I didn’t know anything at all about the town, or know any of the students. The first time I saw New Paltz was the day I arrived to move into the dorm.” And in 1967, once his studies were under way, he found himself drawn to another area he knew little about: Indian music. It proved to be a revelation. “There was a course being offered on Indian music, an elective,” the saxophonist recalls. “I signed up for it, but since I was the only one who did, they decided to cancel it. I ended up working out a deal with the teacher to get private lessons, and it really turned my head around. I was really focused on the rhythms, which are just a matrix of possibilities, since the beats can be subdivided in a million different ways.”

Giardullo continued his immersion in Indian forms for another seven years and eventually became attracted to New Thing jazz, studying sporadically with trumpeters Wadada Leo Smith and Donald Cherry. But the next major turning point occurred when he came across jazz composer George Russell’s book on his Lydian Chromatic Theory of Tonal Organization. A concept that utilizes scales or a series of scales known as modes instead of chords or harmonies, Russell’s methodology greatly influenced the music of John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, and others. “It’s a totally true approach to understanding music, that’s the only way I can explain it,” says Giardullo. “Whenever I hear something that’s confusing, Russell’s ideas will always open it up for me.”