Created By Brian Branigan Streamline Media

Intro Music by Blueberry

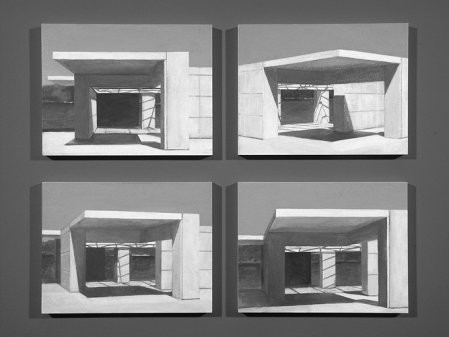

Coxsackie-based painter James Dustin trained as a graphic designer and spent years working with architects on various design projects, including building architectural models. In the late '90s, Dustin began incorporating models into his paintings in a process that evolved into his present method. First, Dustin sketches and then constructs an architectural model— what he calls"pavilions." He then takes his model outdoors, places it on a turntable, and spins it until he finds the "crisp" light he's after. Dustin then paints in his studio from color photos he shoots of the models.Dustin's paintings, as well as his models, will be exhibited as part of a two-person show August 5 through September 6 at the Athens Cultural Center. (518) 945-2136; www.athensculturalcenter.org

—Brian K. Mahoney

Pure Space

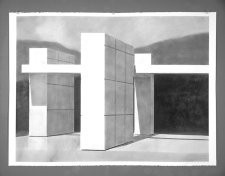

I'm interested in making pure spaces. There's a model, and the model acts as a framing device for the painting. In the paintings you can't tell how big everything is, there are no figures, the scale is ambiguous. You know, kind of making the perfect little space. It's interesting, I live in this historic house. And the reason I bought it was that it was a great space, it has great proportions in terms of rooms and details. And then you look at all the rooms, and they're filled with junk. The idea is that the model is kind of enclosed, but not enclosed, pure space.

Quality and Rigor

If an architect is building a building, there's a quality of thought and rigorousness that goes into it and somehow that's reflected in the final result. And the more buildings one builds, or the more paintings one's made, you kind of have to be careful that they don't become route, in terms of, oh here's another one, here's another one. You kind of have to come back and approach it with a fresh eye, a fresh approach to make sure it maintains that integrity and edge at the same time.

Modernism

I grew up in the '60s and '70s, so modernism had a nasty connotation because it had been played out to some degree, whereas in the '20s and '30s it was the new thing. And so it took my art school education and a lot of work with architects to look back and appreciate the quality of the original structures and original kinds of modernist buildings versus the kind of knock-off stuff that came after.

Rooftop Tableau

One day when I was in Brooklyn, I thought it would be cool to set up a little model or little tableau on my roof. I just set it up provisionally. I made little skylights and blocks, like building blocks, and then photographed them and then threw everything into a box and just said, "OK that's it." When I made the paintings and showed the work, the dealer said, "Wouldn't it be interesting to make some actual models?" And I jumped at the chance. It got more elaborate in terms of having to control and figure out how the thing is going to look as a model. Originally, I was dealing with more interior space, looking outward so it was more of a contemporary look then what the inside of the model looked like. Now I'm more concerned, or as concerned, with what the whole physical object looks like. When I present the paintings, I present them with the models as well, so you have a point of reference and comparison between the model space and the painting space.

Control

I've always been interested in architecture and some of the other series of paintings that I've worked on are actually buildings under construction or in destruction. That's why I've always enjoyed working with architects and watching buildings being built. The unfinished building is in some ways all the more exciting because you don't know how it's going to end—there's still a process to be run out. It still has great potential to be something even better. Especially in the mind's eye, or the architect's mind—this is going to be the best one yet. Some buildings really do turn out pretty well, but a lot of the times there'll be problems. I always look at a new building, with a fine-toothed comb, like oh gee, that detail should have been done better there. And a lot of it is beyond the architect's control. It's the contractor, it's the budget, all these other aspects that come into it. So the half finished building always has to me a great sense of potentialness, it's going to be exciting.

Landscape

Of course I'm interested in the landscape, but I think the landscape becomes sort of a almost secondary in my paintings. I'm kind of more interested in the model. And some of these, as you'll see, the model space kind of takes up more of the painting than the landscape does. I'm more interested, or as interested in the space, the spatial aspects of the model space, than the landscape space. You look at the local landscape and you know that it would make a great painting. And I'm not really a plein air painter. I guess in a way I'm more of a conceptual painter even though they're realistic looking paintings.

Model Airplanes

I guess a part of it goes back to when I was a kid—we built model airplanes. My dad was a pilot and he thought it would be cool if we learned how to build model airplanes. Which we did, my brother and I. And it was good experience, just seeing this kit of parts, these things, and how are all the pieces going to go together, step by step. You do this, you do that, and it comes out. And it's like looking at a building the same way. It can become overwhelming, a project. You look at something and think, "Oh my God, how are we ever going to get this thing done?" But you take it step by step—programming, design, structural details, building, final finishes.

19th-Century Disasters

The arms and armors paintings were very popular with the investment bankers and lawyers, because they're going into battle. You know, it's like, we're ready for battle—suit up. And I also did a series, I did actually a hundred paintings, 25 groups of these plane crashes. And needless to say, I still have those. One of the art dealers I work with said, "Well you know Jim, we work with insurance companies, I don't think they'll be putting these on their walls." But it's interesting, I made a set of sinking ships—a 19th-century disaster—and those were sold right away to a corporate client. It was a nostalgia factor. A hundred years ago sinking ships an instant disaster, you know the same sort of thing. In the 19th century, seeing a ship disaster was sort of like a plane disaster is today, like oh no, did I know anyone who was flying, who was coming across the ocean. So it was an interesting kind of split there between the two subjects.

Photo of James Dustin (page 1) by Jennifer May.

James Dustin with Pavilion Model 166, 2004, painted MDF board & basswood, 9 x 14 x 4.5 inches. Background painting in progress: S212 Columbia County, acrylic on prepared panels, 4 x 6 feet, 2006. (The view is west toward the Rip Van Winkle Bridge and the Catskill Mountains from a vantage point near Olana.) Photo by Jennifer May.

Above, left to right: Charcoal on paper, each sheet 42 x 60 inches: Pavilion Model Drawing B.11, Brooklyn, 2002; Pavilion Model Drawing B.15, Brooklyn, 2002; Pavilion Model Drawing B.20, Greene County, 2004.

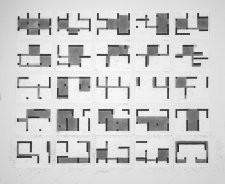

Pavilion Model Plan Drawings 76-100,_ 2003-4, Charcoal & graphite on paper, Each sheet: 11.5 x 14.5 inches_