When Creager emerges, clad in a long vintage dress, she looks like she’s ready to sit in a rocker next to the fireplace and get out her knitting needles. But before we can unravel Rasputina’s yarn, your music editor first needs to use the facilities. Is there an outhouse in the backyard? “Are you kidding? I wish,” says Creager, the band’s “directress”—not entirely joking, it would seem. Thankfully, however, there’s a water closet near the music/sewing room.

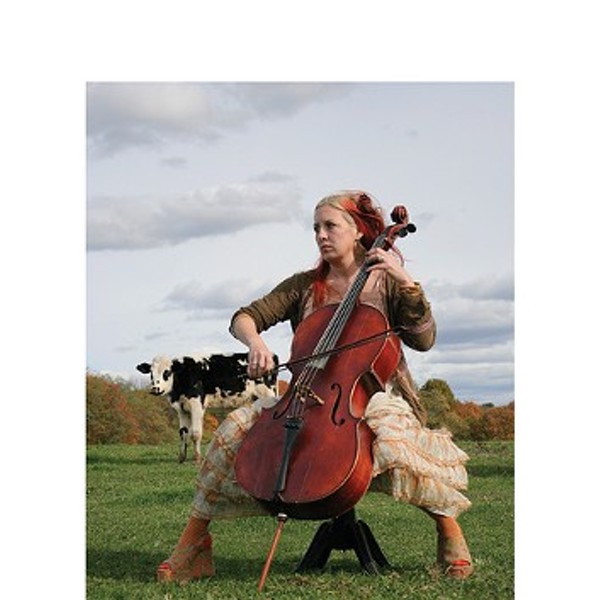

If this all sounds like something out of Laura Ingalls Wilder, well, fans of Creager’s ongoing band likely won’t be surprised. After all, they’ll tell you, Rasputina is almost as well known for its obsessive historical themes and Victorian aesthetic as for its haunting sound and offbeat instrumentation. Started by singer and cellist Creager almost 20 years ago, the group is occasionally augmented by other instruments but currently consists of herself, another cellist, and a drummer. The music, a sort of darkly wistful chamber rock, evokes the Byronic epicisim of Kate Bush and the more whimsical side of T. Rex while peeling away much of the filigree—but not too much.

On the band’s brilliant seventh and newest album, Sister Kinderhook (2010, Filthy Bonnet Recording Co.), the sound is at its wuthering height. Bows skitter robustly across taut cello strings. Banjos are intricately plucked. Harpsichords are tickled deftly. And ankle bells, djembe, and bass drum combine to form the sound of, according to one review, a “Native American drum machine.” In a soaring, mournful voice, Creager weaves tapestries of deep arcana, much of them referencing the Hudson Valley: the plight of female workers in “Kinderhook Hoopskirt Works” (lyric: “There comes an undertone of frantic in their stitchery”); the legend of a sequestered child in “The Snow-Hen of Austerlitz” (“The mother is blind and keeps some birds as pets / That her baby is a human, she forgets”); and the bizarre costumes of rebels during the Anti-Rent Wars in “Calico Indians” (“What do you wear for civil war in 1844 in upstate New York?”). Such scholarly minutiae delivered in song form begs the question: Which interest came first, music or history?

“Hmm, no one’s ever asked me that before,” Creager says, puzzled by the oversight. “It was definitely music, though. My first songs were just normal stuff, about boyfriends and whatever. The historical stuff came much later.” Her own history, though, begins in Emporia, Kansas, where she and two other adopted siblings would often play music together at home with their parents. Her father, a physics professor, had played cello in college and was excited when she wanted to learn the instrument. She set her sights beyond the boundaries of the tornado target of Emporia at an early age. “The biggest employer in town was the slaughterhouse, and that’s where so many of the people around me ended up working,” she recalls. “It gave off quite a stink, too. Everyone called it ‘the Beef.’” The road out was partially mapped by a subscription to Andy Warhol’s Interview. “I’d look at the party pages and see pictures of people at [famed nightspots] the Mudd Club and Max’s Kansas City,” she says. “I got an asymmetric new-wave haircut.”

A summer program at the Philadelphia College of Art was a way station en route to New York, where Creager came in 1984 to study photography at Parsons School of Design. Before long, she was mixing it up in the club world, playing behind downtown drag performers and with indie unit Ultra Vivid Scene. In 1989 she started the Traveling Ladies Cello Society, a duo with fellow cellist Julia Kent, which, thanks to an ad soliciting additional like-minded female players, eventually blossomed into the six-cello strong Rasputina. With its unique setup and gothy, corseted look, the band stood out even on the colorful Lower East Side rock scene, and was soon being courted by the majors. By 1996 the sextet had pared down to three cellists and added a drummer in time for Thanks for the Ether (Columbia Records), an, er, ethereal debut highlighted by eccentric originals (“My Little Shirtwaist Fire,” “The Donner Party”) and suitably twisted covers (Peggy Lee’s “Why Don’t You Do Right?,” Melanie’s “Brand New Key”). In support of the release the band toured with Bob Mould, Porno for Pyros, and even Marilyn Manson, who remixed several of the album’s tracks for an EP. But after a 1997 sophomore full-length, the techno-tinged How We Quit the Forest (produced by Nine Inch Nails drummer Chris Vrenna, who also plays on the disc), Rasputina was still having trouble breaking commercially and relations with Columbia were beginning to crack. “Looking back on it now, I can see [the label] didn’t know what to do with us. I guess they thought we were going to be the next Enya or something,” says Creager. “I mean, three chicks in bloomers playing the cello? Come on.”

After shuffling lineups tumultuously and parting ways with Columbia, the band went on hiatus. Kent left, going on to play with Antony and the Johnsons and others. Creager has had her share of illustrious side gigs as well: Manson, the Pixies, Screaming Trees, Belle & Sebastian. And then there was the stint with Nirvana for the 1994 In Utero tour, an experience she jokingly credits with teaching her “lessons in avoidance of immense fame.” “Kurt Cobain was just like somebody you or I would know,” she says. “A for-real, funny guy. But I could see what the huge rock business was doing to him, mentally and emotionally. He was a really sweet person who didn’t belong in the middle of this gigantic milieu. It just didn’t fit his personality. All of that left an impression on me.”

A reactivated Rasputina signed to Moby’s Instinct imprint for 2002’s Cabin Fever, which continued the dark, distorted rock style the act had been working in previously, and 2004’s Southern Gothic—in more than one sense—opus, Frustration Plantation. Creager started her own Filthy Bonnet label to release the live A Radical Recital in 2005, the same year she moved to Columbia County. “A friend of mine bought a house up here, and when I came to visit I just really loved [the area],” says the singer. “There’s something that draws people here really strongly. I tried to move up several times before, but it took me a while. The cult of New York City has a lot of strength, too.” After she’d finally made the move came Oh Perilous World (2007, Filthy Bonnet), whose songs touch on 1816’s “Little Ice Age” and the life of Mary Todd Lincoln, as well as contemporary topics like the Iraq War and post-Katrina New Orleans.

Dominated by acoustic instruments, Sister Kinderhook represents a return to Rasputina’s true steampunk roots. The inspiration for the album’s regional motifs was a dusty digest dug up in a friend’s basement. “She found this book from the late 1800s that’s kind of like a census, a directory,” Creager explains. “It has the names of everyone in the town and their occupations, mentions a medicinal herb farm run by two brothers. I saw some real mysteries in there. I made field trips to sites like Olana and Lindenwald to do research. There’s a lot of history in Columbia County to draw from.”

It also appears the legend of Rasputina has given a new generation of musicians something to draw from. The group’s autumnal sound and dark-cabaret image are all over younger acts like Joanna Newsom and the Dresden Dolls—though Creager doesn’t see it that way herself. “If that’s true, I didn’t notice it myself,” she says. “I did spend a few years feeling like I didn’t get any respect, though. [Laughs.] So it’s nice to hear it.”

One artist she’s heard it from is Alissa Anderson, who’s performed with freak folk bands Two Gallants and Vetiver. “In high school I was a little punk but played the cello,” says Anderson, who mail-ordered an early seven-inch after coming across a fanzine ad. “Rasputina was hugely influential to me as a young female cellist interested in what lay beyond orchestral music.”

Another rebellious young player to be inspired by Rasputina’s music is Daniel DeJesus, who in 2008 had a dream fulfilled when he became its first-ever male cellist (the group has had mainly male drummers over the years, but currently that chair is occupied by a woman, Catie D’Amica). “I was so excited to audition [for Rasputina] because I was already such a big fan,” says the Philadelphia cellist, who Creager met when she saw his old band, also called DeJesus. “I loved Melora’s music because of the combination of rock and classical music, and the stories in her songs are just so bizarre. Like her, I kind of live in my own make-believe world, so that aspect [of the band] really appealed to me too.” (DeJesus also plays in the trio TivaTiva.)

Outside of the make-believe world of her band, Rasputina’s matron is a real-life mother with two daughters: 11-year-old Hollis, who lives in New York, and 10-month-old Ivy. “Before I became a mom I was a really competitive person,” Creager reflects. “I don’t think anything other than having kids would’ve taught me to be less self-centered. And I’ve found that being a mother somehow also helps my singing. I’m not sure why, but I feel more relaxed and in control. There’s less fear.” Naturally, lengthy tours will have to wait until Ivy grows a bit, but in the interim Rasputina is able to do shorter jaunts and the occasional festival date. Between gigs, Creager supplements her income with a successful line of handmade jewelry that includes the prefect fan keepsakes: necklaces made from old cello strings.

Warp ahead to the year 3010. A little girl with esoteric tastes finds a dust-covered record cover in the basement of an old house. The front bears the name Rasputina and the vinyl inside is still intact. When the curious child places it on her antique turntable and lowers the needle into the groove, what would Creager hope she experiences?

The singer thinks a moment. “I guess I’d hope she’d be surprised,” she says. “And that she liked the music enough to share it.”

Not a difficult outcome to imagine, really.

Sister Kinderhook is out now on Filthy Bonnet Recording Co. www.rasputina.com.