Yes, there really is a Medusa, New York. For the past 10 years, it’s been a second home to a literary couple who, while not at all monstrous, do seem a bit superhuman.

A professor of journalism at Columbia University, Helen Benedict has written five novels and five books of nonfiction. In April, Beacon published her wrenching exposé The Lonely Soldier: The Private War of Women Serving in Iraq, and SoHo Press is about to release The Edge of Eden, an elegant, often wickedly funny novel about a British family’s disintegration in the last-gasp colonial outpost of the Seychelles islands in 1960. Each is a marvel on its own terms; that they come from the same writer’s hand smacks of sorcery.

Benedict’s husband, Stephen O’Connor, is equally protean, publishing short fiction and poetry (Rescue; 1989, Harmony Books), memoir (Will My Name Be Shouted Out?; 1987, Touchstone Press), and nonfiction (Orphan Trains: The Story of Charles Loring Brace and the Children He Saved and Failed; 2004, University of Chicago Press) between teaching gigs at Columbia and Sarah Lawrence. He also writes a hilarious set of driving directions, guiding the uninitiated through T- and Y-shaped intersections, a misleading road sign (“IGNORE IT”), past Camp Medusa (“An Adventure in Christian Living”), and on to a series of winding back roads. Just as the thought dawns that he recently published a story in the New Yorker about the Minotaur, and might have a thing for insoluble mazes, the couple’s pristine Victorian farmhouse comes into view.

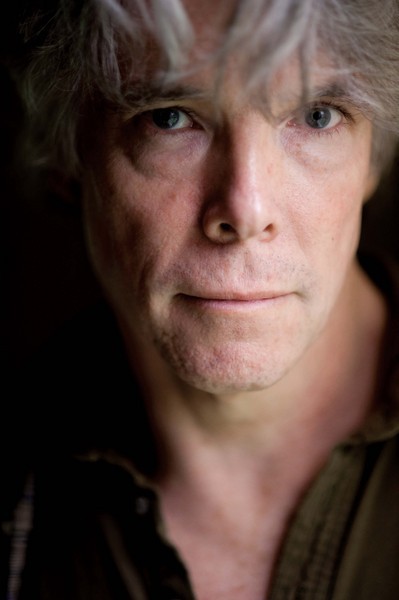

They’re a striking pair. Benedict is petite and whippet-thin, with enormous green eyes and a piquant face; born in London to American parents, she has a distinct British accent. O’Connor, broad-shouldered and handsome, grew up in New Jersey, the son of an Irish immigrant father and a French mother. They met as graduate students in a Berkeley writing class taught by Leonard Michaels. Their bond was immediate. “I looked at Steve and thought, ‘Wow!’” says Benedict. “And we were each other’s favorite writers in the class.”

Benedict had just arrived in America, fresh from a job at “a really crappy paper” in England. The pull between fiction and journalism has always been with her. “Fiction was my first love, ever since I was eight, but I wanted to make a living,” she says. “I also have this really political, burning side. Writing nonfiction is more of an activist impulse than anything else.”

Women Warriors

The Lonely Soldier came out of anti-Iraq War protests at which she heard soldiers and veterans speak out against war. Realizing that “women soldiers had their own stories to tell,” she started to interview them. Initially, she wanted to find out why women would enlist in the military, and what it was like to be a woman active in combat. What she uncovered—from deceitful recruiting techniques to relentless sexual harassment and frequently unreported assaults by male colleagues—makes for gut-twisting reading. The Nation’s Katha Pollitt wrote, “The Lonely Soldier will shock you and enrage you and bring you to tears.”

Benedict structures her narrative around five women who fought in Iraq between 2003 and 2006. She interviewed around 40 female soldiers, eventually weaving an Off-Broadway play, “The Lonely Soldier Monologues,” from the women’s own words. (Specialist Mickiela Montoya: “There are only three things the guys let you be if you’re a girl in the military—a bitch, a ho, or a dyke.”)

“It was very important to me that it be a documentary play and that I not mess around with their words,” she says. “It’s not my story, it’s their story. I wanted to step out of the way, be a vehicle.” When director William Electric Black staged the play at the Theatre for the New City, several interviewees came to see it. “It was surreal and hard and traumatizing for a lot of them, but also cathartic and amazing,” reports Benedict. “They went out for drinks afterward with the actresses; they were like sisters.” Nevertheless, she called afterward to make sure they were all right.

While researching her 1985 book Recovery: How to Survive Sexual Assault (1985, Doubleday), Benedict trained for 10 weeks as a rape crisis counselor at St. Vincent’s Hospital. Another book, Virgin or Vamp: How the Press Covers Sex Crimes (1992, Oxford University Press), applies a different lens to the same topic. “From a very early time, I’ve been infuriated by injustice of all kinds, and especially this,” she asserts. “Rape itself is such a ghastly act, and its victims are treated so badly by society—they’re blamed for it. That double injustice—I just can’t stand it, it gets me inflamed. It stands in for all kinds of injustice: race, class. It’s always one on top of another and another.”

Books without Borders

Benedict is currently writing a new novel set in Iraq. “There were whole inner layers that I came to understand that were more intuitive,” she says. “What do you feel when a prisoner throws excrement on you, when your sergeant is making passes at you all day long, when someone you thought was a friend assaults you?” About half the novel is narrated by an Iraqi woman. It’s a nervy choice, but Benedict, who conjured the voices of a Dominican teen mother in Bad Angel (1997, Plume Press) and Greek islanders in Sailor’s Wife (2000, Zoland Books), is unfazed. “Writers have been crossing cultures and genders and ages and times forever,” she says. “I think we’ve gotten narrow about that, maybe because of all this PC business.”

The Edge of Eden’s third-person narrative dips freely into the minds of a wide range of characters. “I didn’t want only the British point of view,” Benedict says. “In old-fashioned novels, the natives, quote unquote, are never full human beings.” Here, Sechellois Marguerite Savy assesses her British employer: “At times Penelope reminded her of the local cattle egrets, stalking around on spindly yellow legs, eyes wide and empty, with no clue as to what they were really seeing.” (Marguerite may be shortchanging Penelope, who can look at her onetime lover and his wife and notice “his hand resting on her plump shoulder with the casual possessiveness of a man holding his bicycle.”) Benedict’s prose glints with such deft observations, along with vivid evocations of a landscape where even the plants appear oversexed.

Imagination at Work

In 1960, when Benedict was eight, her family moved to Seychelles. “My father was an anthropologist and my mother became a de facto one, helping him with his fieldwork,” she says. “I had this whole rich experience and many memories and had never used them in my writing in my whole life, partly because I shy away from anything autobiographical.”

Though Zara, the older daughter whose dark fixations precipitate some of the novel’s most wrenching twists, is the same age Benedict was during her family’s stay in Seychelles, her fictional family is based on London classmates whose parents were sent away during the Blitz, raised by nannies, or farmed out to boarding schools. “How do people learn to be parents if they were exiled from their homes and basically grew up without a family?” she asks. “That began to fuse with the kind of decadent way European adults behave when they’re in the tropics. Even at age eight, I was definitely aware of that with the British adults in Seychelles.”

Benedict’s approach to fiction is largely intuitive: “I never think out novels in that much detail. The imagination that’s at work when what you’re actually writing is so much more intelligent than the brain that plots and plots. I tend to just pour out a novel and see what happens, do it really fast, then spend years rewriting.”

First Readers

O’Connor and Columbia County novelist Rebecca Stowe are always her first readers. Benedict shares her work “when I get blind to it—when I know it needs work but don’t know what.” Her husband concurs, adding, “We literally started our relationship showing each other our work, and we’ve been doing it ever since.”

Several years ago, on vacation in France, O’Connor set himself a challenge. “I decided to write 14 lines of verse every day. My only requirement was that it could not make sense,” he says. “I was sick of the way I’d been writing. I wanted to explode out of my voice, smash my voice. I’d sit down to write poems and I had to surprise myself with every line. I found I was getting at material I’d never gotten at in my life. It completely changed the way I wrote.” He just sold a story collection to Free Press for publication in June 2010. He’d published many stories in magazines but found little interest in a new collection until “Ziggurat” appeared in the New Yorker. His agent sold the book that weekend.

Accomplishment seems to run in the family: O’Connor and Benedict’s son Simon plays lead guitar in rising alt-rock band Amazing Baby, and college-bound Emma has won scholarships for her writing. When they were younger, their parents made charts, dividing the days so they’d each have time to write. “It sounds awfully mechanical, but I think it was a good idea,” says Benedict. “You knew exactly when you were going to write, and the nonwriter would handle all phone calls, chores, et cetera. It’s very good for not messing about. If you only have three or four hours, they become sacrosanct.”

O’Connor agrees. “Before we had kids, I could only write when I was inspired. Then it became, ‘My god, if I’ve got five minutes, I’ll write for five minutes. If I’ve got 10 hours, I’ll write for 10 hours.’ Otherwise, I wouldn’t be writing at all.” He shakes his head. “It’s hard to do all this and be a husband and father.”

Benedict snuggles next to him on the couch. “Are you a husband and father as well?” she asks teasingly.

“Sometimes,” smiles O’Connor. “We’re maniacs.”

Helen Benedict will read from The Lonely Soldier and The Edge of Eden at the Hudson Opera House on October 17 at 8pm.