In the early 2000s, when Ralph Erenzo and his son Gable tried to open a campground for rock climbers in the shadow of the Shawangunk Ridge called Bunks in the Gunks, opposition from deep-pocketed neighbors derailed the project.

A serial entrepreneur who sought to produce a profit with the property and avoid another uproar, Erenzo learned that a farm use, which no entity could contest, also included use as a winery. Tending vines seemed complicated, so while researching the fine print of the state’s alcohol laws, he discovered a new distillery category with a reasonable $1,450 fee to get started.

However, neither he, nor his son, nor his friend and business partner Brian Lee knew anything about distilling. So they learned, using tea kettles on a stovetop. Ralph took care of the business end, Lee and Gable tended to the equipment and made the hooch.

In 2003, Tuthilltown Distillery received its license, joining a miniscule band of enterprising spirit-makers in New York who revived an industry that almost died with Prohibition.

In the early days, Tuthilltown finished their bourbon in tiny barrels to accelerate the aging process and called it Hudson Baby Bourbon. Arriving in squat 375-milliliter apothecary bottles with retro, minimalist labels, it carried a premium price point that bestowed cachet. Erenzo sold cases from the trunk of his car and they eventually scaled up production and distribution. “We couldn’t make it fast enough,” he says. “Whatever we made, we sold.”

He and other allies, including Kim Wagner at Stoutridge Distillery and Winery in nearby Marlboro, lobbied Albany to allow distillery tastings and on-premises sales by focusing on helping farmers, creating jobs, stimulating tourism and generating tax revenue, laying the groundwork for New York’s craft distilling boom.

Best of Times, Worst of Times

Now, as the advent of craft distilling in the valley reaches the two-decade mark, the industry is at a crossroads.

Success seemed to breed more of the same as making spirits became sexy, people gushed over the rediscovery of an ancient craft, and distilleries opened across the state. But savvy local entrepreneur types weren’t the only ones paying attention. In 2010, a multinational corporation based in Scotland bought a stake in Tuthilltown, signaling a sea change, and in 2018, Proximo, parent company to Jose Cuervo, bought Black Dirt Distillery in Warwick.

On a smaller scale, an investment group now owns Catskill Distillery in Bethel, which renamed it the Alton Distillery; and The Spirits Lab will soon take over Palaia Winery and Meadery in Highland Mills and keep their Newburgh location as a showroom.

The Hudson Valley’s distilling scene rose in tandem with New York City’s, and they now seem to be shifting together. Last year Widow Jane, one of the oldest downriver brands (named for a mine in Rosendale), sold to bourbon giant Heaven Hill (of Evan Williams and Rittenhouse rye to name a couple). The trend toward acquisition is also happening upstate. Based in the Finger Lakes area, Constellation Brands, a Fortune 500 company that owns ubiquitous names like Modelo beer and Svedka vodka, took a minority stake in Rochester’s bourbon-forward Black Button Distilling in 2019.

And yet, as some of the smaller distilleries get snapped up, many others have shuttered statewide. Numbers are down from 206 in 2020 to around 160 in 2023 according to the New York State Distillers Guild.

The Hudson Valley is somewhat insulated from this negative trend due to its proximity to New York City markets and its status as a tourist destination, but industry experts see possible storm clouds on the horizon for some local distilleries. “I’m a big fan of what’s going on in the Valley, but there are two or three more distilleries hanging on by a thread,” says Carlo DeVito, an author and liquor industry expert based in Ghent. “It’s much more difficult nowadays. There are too many craft beverage businesses in general, and often, the land is more valuable than any distillery or winery that operates there.”

And consumers should get ready to pay more for that pour as inflation and higher interest rates create pressure on small brands. The price of oak barrels rose from $260 to $320, says Pietro Bortolotti, primary partner at Alton Distillery. Susan Johnson at Denning’s Point Distillery in Beacon says that the cost of glass bottles has doubled.

A 2020 report commissioned by the Distillers Guild estimated that the craft spirits industry pumped $3.2 billion a year into New York State’s economy. That seems impressive, but most Hudson Valley-based operations are so small that they are unlikely to attract outside capital, says DeVito, who subtitled a foreboding recent blog post “The Craft Beverage Boom is About to Go Bust.”

Some distillers generate income by sponsoring events and diversifying their revenue streams. For example, Orange County Distillers operates Brown Barn Farms, an off-site serving space and entertainment venue. The rustic roadhouse at Hudson Valley Distillers in Clermont also stimulates sales. Hudson House and Distillery in West Park, which operates a restaurant and wedding venue, plans to add guest suites.

And long before Proximo called in 2018, the partners behind Black Dirt Distillery crafted eau-de-vie and applejack, created the Doc’s Cider brand, opened a bar and restaurant at Woodbury Commons outlet mall, and established the Warwick Valley Winery and Distillery—a bar, eatery, tasting room, event space, retail outlet and music spot on an orchard two miles from the distillery.

Other properties that might entice an outside buyer include bourbon-centric Taconic Distillery in Stanfordville, which recently doubled storage capacity, and Dutch’s Spirits in Pine Plains, which is on hiatus at the moment but could be up and running almost overnight according to DeVito.

Taconic fills 1,400 53-gallon barrels each year. That’s big—for New York. (For reference, a few years ago, bourbon giant Jim Beam passed the half million mark per annum.) Founder Paul Coughlin, a former Wall Streeter, has yet to field any offers. But for now Taconic’s future seems safe: Coughlin says he’s having too much fun working with his wife and daughters to consider selling anytime soon.

Pioneering Spirit

In many ways, Tuthilltown has been setting the pace for the region’s distilleries with every milestone from opening, selling and generating PR for the area.

After Tuthilltown released its first batch of Baby Bourbon in 2006, their array of press clippings, including a New York Times article and lots of European coverage, attracted the attention of William Grant & Sons. The Scotland-based family-owned company’s portfolio includes brands like Glenfiddich, Hendrick’s, and Tullamore D.E.W., among many others. “I knew I would get a lot of media attention just for being the first whiskey from New York since Prohibition,” says Erenzo.

Grant put cash on the barrelhead in 2010, buying the Hudson Whiskey brand just as cocktail culture bloomed and bourbon began to boom. Seven years later, they went all-in on the 36-acre distillery for an undisclosed sum. Capacity increased and now “the product is the best that’s ever come out of the distillery,” Erenzo says. “We got the best chemists and better systems.”

In 2020, Grant revamped the distillery’s marketing, promoting their flagship brands as Hudson Whiskey NY, boosting the bottle size to 750-milliliters and adopting a design scheme resembling New York City subway signs. They also introduced color-coded labels and cute names: mustard-yellow for Bright Lights, Big Bourbon and leaf-green for Do the Rye Thing.

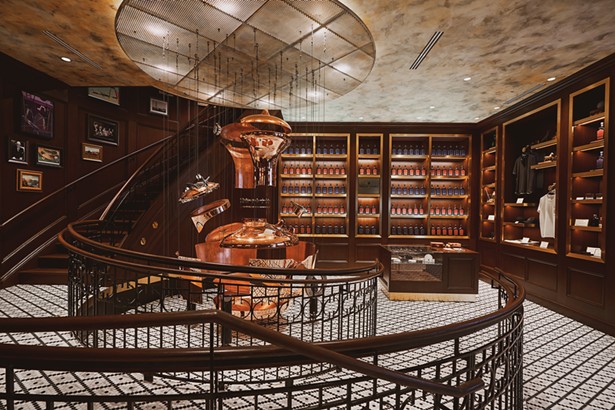

Proximo, who also own Kraken rum and Old Bushmills Irish whiskey, bought Black Dirt Distillery in 2018 to service Great Jones, their Manhattan bar, restaurant, distillery, and whiskey brand, which opened in 2021 to much fanfare. They promoted it as the first legal booze-making operation in the borough since Prohibition and put millions of dollars into creating a four-story, 28,000-square-foot shrine to the distiller’s art.

The acquisition provided various upsides for Proximo. For one thing, the company gained access to ready-made product. Bourbon distillers who start from scratch must wait for the first batch to age and often source until the product is ready. Bottles of Great Jones are now filled with output from in-house and the juice distilled in Manhattan is stored in Warwick.

In 2021, a group of 10 investors took over Catskill Distilling at the doorstep of Bethel Woods Performing Arts Center, renaming it the Alton Distillery. Their stalwarts are a rye, a bourbon, and Peace Vodka. The deal included a considerable amount of bourbon and other aged spirits for the new owners to play with, according to Bortolotti. This fall, they are offering limited editions of eight-year bourbon and a blend of bourbon, wheat whiskey, and buckwheat spirit, all of which is 10 years old. Distiller Calvin Burk is forging the establishment’s identity and they plan to open an upscale bar and a restaurant called Rain Dogs, after the Tom Waits album.

Fight for the Right

As corporations exert their influence on the local liquor industry, New York’s small-scale distillers (and cider makers) are struggling to keep up as they battle to change state laws that forbid them from selling over the internet—a key difference from wineries, which are permitted to do so. Brewers, too, can sell online, though they must apply for a special permit.

During Covid, Albany allowed direct-to-consumer sales of cider and spirits for 15 months, but reinstituted the ban in 2021. The state Distillers Guild is waging a robust lobbying campaign but keeps getting rebuffed. “Big wholesalers don’t want any change,” says DeVito in Ghent. “They spend a lot of money to preserve the status quo—not just in New York.”

Industry veteran Kim Wagner at Stoutridge says that as the measure sits in limbo, the inactivity will kill the state’s distilling industry by attrition and that local wineries are only hanging on because of their direct access to consumers across the country. “All of my customers who buy spirits at the distillery are one-offs,” she says. “They go home, and I can’t restock them. And, visitation at tasting rooms has plummeted. People have learned how to stay at home.”

For Facquet at the Distiller’s Guild, “whether it’s beer, cider, wine or the hard stuff, alcohol is alcohol,” he says. “We just want it all to be treated equally.”