Thermal Mass in Accord

The Green Engineering Evangelist

[]

Joe Britt Jr., stay-at-home father of three and autodidact engineer, is extremely frustrated, rather like the architect Howard Roark in Ayn Rand’s breakthrough novel The Fountainhead, who ultimately chooses struggle over compromise. While Britt is convinced his ideas for creating extremely energy-efficient homes using thermal mass building techniques are the way forward, he’s constantly being shown the door politely by the rich or powerful rainmakers he approaches.

The most important thing to know about thermal mass construction, or TMC, is that its ardent proponents get very excited describing why it’s so stupid to heat or cool air versus maintaining the temperature of hefty concrete and Styrofoam walls.

Part of the problem is certainly Britt’s delivery. Deliciously nice, if decidedly immodest on the subject of energy retention, Britt’s so left-brained his possibly profound treatises on creating a postconsumerist America are painful to read. Here’s a sentence from a blog post titled “Saving Our Banks!” from April 12: “Trees that have been fallen due to storms from the past just littering the forest floors.” Nevertheless, “the public’s reluctance” to adopt Britt’s detailed vision for marching toward a carbon-neutral utopia is “at least irritating and lately depressing,” he admits. But Britt thinks there may be a conspiracy to keep America hostage to big oil wed to a construction industry determined not to evolve.

“If we change residential architecture, we change everything about society as we know it. Right now, homes are built in this extremely inefficient tethered-to-the-grid way, and rethinking that poses a huge threat, it’s disruptive,” says Britt. “There are about 150 million houses in America. If we built thermal mass homes—they can’t burn down and can easily stand for hundreds of years—you’ve completely altered banking, because there goes demand for mortgage and construction loans.”

Britt, a handsome, can-do Syracuse native, took leave a decade ago from membership in Local 417 Ironworkers, a labor union that’s notoriously difficult to penetrate. The steelworker’s union is known for a comprehensive five-year apprenticeship program that Britt managed to bypass. A born engineer, he’s worked in construction practically since he could walk. Britt says his atypical leap to foreman created resentment.

“I had access to the big architects, the big engineers, so that’s where I gained the confidence to think at this scale,” says Britt, whose wife Meghan, whom he met in college, works for Central Hudson. She’s been there 23 years.

The couple made $200,000 on the sale of their first home in Highland, a fixer-upper Britt essentially reinvented. When daughter Avery, their firstborn, was diagnosed as a toddler with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and given a grim mobility prognosis, the new parents investigated alternative therapies and eventually decided they needed an indoor pool. Joe figured out how to build a home in which that was not going to be a financial burden.

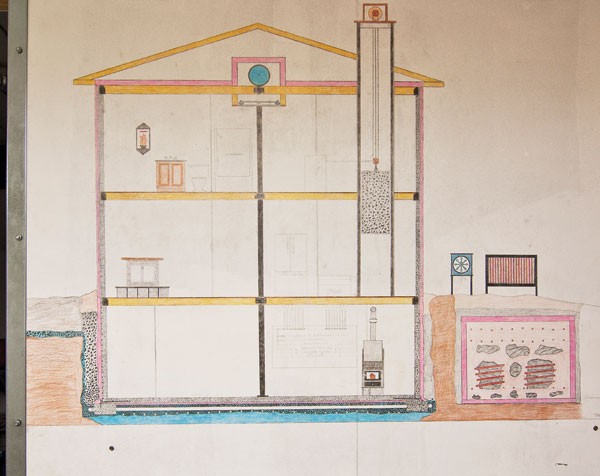

In 2002, they paid $45,000 for five raw acres on the Rondout Creek in Accord with a view of Mohonk Mountain House. The family lived in a cramped, low-rent apartment while Britt built their three-bedroom, three-and-one-half bath house, practically solo. Including the separate pool room, it has a total living space of 4,400 square feet, counting the basement. It took two-and-a-half years and cost about $300,000 to build. There’s a long driveway, plus a huge goldfish pond. They keep chickens. Brownie, a Maltese-Yorkshire terrier mix, rules the roost.

Britt figures there’s about 60 tons of concrete in his house. It cost 20 percent more per foot than conventional construction. There’s no furnace: A pellet stove, used only on winter nights, keeps the whole house warm. A circulating pump connected to a solar-powered hot water heater soundlessly moves water-filled pipes built into the floors and walls. Radiant pipes are key to how TMC sustains an even ambient temperature. While his passive solar house is on the grid, Britt says it wouldn’t be difficult to make it self-sustaining. The only reason the skilled electrician didn’t build a specialized generator was that he was running out of money and time. The 12-by-27-foot pool is kept at 81 degrees Fahrenheit. Total annual energy cost is $1,200.

Avery, now 12, plays soccer and doesn’t take any medication; Britt says that’s clearly his greatest achievement. But now he needs to make some money. Several attempts to get his own construction business off the ground have collapsed. He’d like to be hired by homeowners looking to retrofit conventional construction with a TMC energy envelope. Britt’s on the Town of Rochester Environmental Conservation Committee; they recently sent him on a watershed management retreat at the Omega Institute. Occasionally he’s asked to give a speech on his ideas for “creating a society of caretakers instead of consumers.”

Otherwise, when he’s not busy being Mr. Mom, Britt spends his days trying to increase traffic to his website and Twitter account. After discovering the hard way that it just wasn’t possible to sell his exhaustive package of Frank Lloyd Wrightian ideas, on Earth Day 2012, “I just went ahead and posted it all,” says Britt. “It’s just that important.”

At Britt’s website, Whatifpureenergy.com, he suggests that appointing teenagers as environmental stewards would keep them out of trouble. He recommends that towns of the future feature an advanced underground infrastructure based in part on anthills. When it’s suggested that perhaps he’s trying to take on too large a job, reengineering all of society, with scant credentials, Britt laughs.

“Well, that’s really what I do all day when the kids are at school. This house is so well-built it requires almost no maintenance,” he says. “I’ve got people following me all over the world, just not many of them. This week I picked up someone from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory—that’s the top energy think tank.”

Operated by the US Department of Energy, the Berkeley lab conducts unclassified research experiments. The government’s secret energy experiments are conducted at Los Alamos. Britt’s also had Twitter followers from the Environmental Protection Agency.

Thermal Mass Construction 101

Britt poured his walls in place using insulated concrete forms, or ICFs. Building with ICFs is less expensive and more flexible design-wise than using manufactured precast thermal mass panels. Dow Chemical Company’s T-Mass is one popular readymade brand. With the proper equipment, precast walls can go up in a day, whereas ICFs take 27 days to cure.

TMC’s at heart an expansion of the idea that a full refrigerator uses less energy than an empty one, because anything denser than air will better store the cold. A 3,000-square-foot home with 10-foot ceilings has about 12.7 pounds of air inside that wants to dart about, heat up, cool down. But the walls of a thermal mass house stubbornly resist temperature gains or losses. There’s also something called the thermal mass effect. Thick walls absorb heat during the daytime which is released to the interior at night. That’s why desert dwellings have traditionally been made of adobe, or mud bricks. “It may sound complicated, but really, this is something the cavemen understood,” says Britt.