While the following story is what will run in Chronogram’s April 1 print edition, this update provides the most current events, still ongoing.

In part that includes legal action. As of last night, attorneys for Martinez, Cheryl David and Paul O’Dwyer, were rushing their last-minute argument that, in part, ICE is ignoring federal law. According to David, neither she nor O’Dwyer were notified by ICE that they were about to deport Martinez. That’s a requirement according to ICE’s own 2009 guidelines.

Critically, David said, Martinez has filed for a special form of visa that protects people who come forward to help the police, and the US Citizenship & Immigration Service asked David for evidence to support the claim and gave her office until late May to produce it. Under that visa process, ICE’s guidelines say the department “should also consider favorably…relatives who rely on the alien for support.” Martinez has a wife and three American children. “Martinez has a pending U Visa application,” David said. “But at this point, according to what we’ve been told by Mr. Martinez, though unconfirmed by ICE, they still intend to remove him despite all his equities, and a family to support in the U.S.”

The rally Sunday drew well over 100 protestors. And it brought a response from officers of the Orange County Sheriff’s department, who continually tried to shoo the group of adults and their children, and all of Martinez’s family, away from the jail grounds. At one point when the chant of “Bring Luis home!” was loudest and the protestors were closest to the facility, there was a cry coming from within the jail, with the hoots audible on the street outside the prison walls. In turn that led to a warning from officers that the crowd would have to disperse or risk arrest.

At that point—speaking through Sharia, her eldest daughter, as her interpreter—Tina Martinez thanked everyone for coming, “Not just for Luis, but in support for all the families who are going through this, because it’s truly really very hard.”

Whether such public actions matter is anyone’s guess. However, there’s legal precedent for arguing that Martinez has the right to remain in the US while his visa claim is argued. That 2017 case, successfully won in Illinois, provides a possible pathway for Martinez to be freed. Yet his attorney, David, said he might still be deported to Mexico and have to await a verdict there, possibly for years.

———————————————————————————-

On the morning of January 16, businessman Luis Martinez was arrested by agents of the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency outside his office in New Paltz.Martinez’s detention and possible deportation is part of a wave of recent crackdowns by ICE across Upstate New York. His story is both distinctive and typical of undocumented residents, part of a larger narrative caught in the crosshairs of a bitter national debate on immigration.

Luis Martinez was born in Mexico in 1979. His mother, Maria Raymundo, was married, and had another younger son, Jesus. When Martinez was eight and Jesus was six, her husband was murdered by the Mexican mafia while the family attended a wedding. Terrified the mafia would come for her next, she took her two boys and fled to the US to claim asylum, which she was granted—but her sons were not. They had to enter the laborious process toward getting green cards.

The family was poor and moved first to Florida, and eventually to New Paltz, in the heart of the Hudson Valley. They worked and lived on Dressel Farms, south of town, picking apples and strawberries. Both brothers went to New Paltz High School and Raymundo remarried and gave birth to two more sons. Martinez never got full citizenship, but because he came to the US as a child, didn’t behave like a foreigner. His half-brother, Sergio Raymundo, said “America is his home. We’re New Paltz boys. This is our town.”

This story, however, isn’t just about Martinez, who has a wife and three US-born children, ages 11, 12, and 16. It is about how ICE’s actions have put a chill on the Mid-Hudson Valley immigrant population, and how a single arrest has a profound impact on a community. We talked to dozens of people who know Martinez well beyond the bounds of New Paltz, and we kept meeting undocumented, DACA, green card holders, and citizens who had met him, befriended him, and worked with Martinez.

While we weren’t able to meet with Martinez in person (ICE doesn’t make it easy for journalists to speak with detainees), we learned he’s more than socially influential. He’s cast an outsize economic shadow for an undocumented immigrant.

While New American Economy shows that immigrants nationally are 28 percent more likely to be entrepreneurs than natives and that in New York’s 19th Congressional District they contribute $460 million annually to the local tax base, Martinez is a bigger fish than most. His development firm, Lalo Group, has construction projects in four of the five boroughs of New York City. While staff at his New Paltz office were gun shy about talking to the press in the wake of Martinez’s arrest, the company employs dozens of people at its New York City job sites as well as in projects closer to home, such as at Zero Place, a high-tech geothermal and solar powered multi-use complex in New Paltz. The project faced significant headwinds from some town elders who like the village of 7,000 to stay relatively sleepy. Nonetheless, it eventually passed village planning board approval, and Martinez himself took a minority financial stake. Construction has just begun.

So, partly people know Martinez because of his work, and partly because he’s a local guy made good. Three weeks after Martinez was detained, nearly 300 people crowded into yet another one of Martinez’s businesses, La Charla, a Mexican restaurant on Main Street in New Paltz. Well-wishers wrote notes on heart-shaped cutouts while sipping beer and margaritas. With Valentine’s Day looming, hundreds of the cards were packed into banker’s boxes and hauled by a group of Martinez’s friends to the Orange County Correctional Facility, in Goshen, where he’s in detention. The boxes arrived on February 13, just in time for the first Valentine’s Day Martinez has spent apart from his wife, Tina, since they met 19 years ago.

A few days later, Tina said she was astonished by the community support. One of her friends, Alex Baer, said Tina is a lot more introverted than her husband. Tina said that before the event for Luis, she never quite felt comfortable in New Paltz, “Like we were invisible.” Their eldest child, 16-year-old Sharia, said the outpouring made her mother feel like she was finally welcome. “With how hard this situation is,” Sharia said, “That night lifted everyone’s spirits.”

A Pattern Under Trump

ICE’s detention of Martinez follows a pattern of ignoring an immigrant’s legal status. Martinez is pursuing what’s known as a U Visa, a special form of protection—but it didn’t shield him from ICE. In the late 1990s, peak gang violence in the US spurred Congress to pass the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act in 2000. Offering a kind of amnesty, this law created the U Visa, among a few other forms of deportation protection. To be eligible for a U Visa, in exchange for coming forward and giving evidence as well as testifying against criminal gangs, victims would gain some immunity from deportation, including help getting a green card and working toward citizenship.Martinez’s case is especially strong. In 1999, he witnessed the gangland killing of his brother, Jesus, in Newburgh. Jesus wasn’t the target: The leader of a Mexican gang known as La M was being pursued by a rival gang, but Jesus caught the bullet instead. Subsequent to the murder, Martinez helped the police. He would become eligible for the visa a year later, after Congressional passage, but he only learned of it, and applied, in 2016.

Nevertheless, since Trump’s January 25, 2017 executive order, ICE is regularly detaining every class of citizenship seeker, including green card holders and other applicants.

Sarah Pierce, an analyst at the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute in Washington, said Trump’s ICE doesn’t seem to care about pending visas. “In the past ICE would give deference, by closing removal proceedings.” Today, however, she said, “Just because you have that piece of paper doesn’t mean you’re protected.”

Lee Wang, staff attorney with the advocacy group, the Immigrant Defense Project, paints Trump’s ICE in clear contrast to Obama’s ICE. “Obama was no saint on deportations, but later in his presidency ICE prioritized arrests of people with a serious criminal history, who posed a threat to public safety,” Wang said, referring to an ICE program known as Priority Enforcement, which focused specifically on higher-level criminals and known gang affiliation. But when Trump came to power, ICE reinstated an earlier Obama program called Secure Communities. The system cross-checks anyone arrested for any form of crime against a national database, and ICE is now attempting to arrest everyone who crops up, regardless of the level of offense.

That’s resulted in the highest rates of detention since ICE was created in the wake of 9/11, with an average of roughly 50,000 detainees per month as of early 2019. Last year the total number of arrests hit 159,000, an 11-percent increase compared to 2017 and a 30-percent increase compared to 2016, according to ICE’s 2018 fiscal year report. (A larger percentage of those arrested wound up detained, too, and a study by the New York Times shows that as much as 71 percent of these detainees wound up in private, for profit prisons.)

“They’re being purposefully indiscriminate,” Wang continued, characterizing the “dragnet” approach of ICE since Trump took office. “The order said to deport people to the fullest extent practicable. What does that mean for the millions of people who have a green card, who actually have documentation?” In fact IDP’s 2017 data shows that 20 percent of people targeted by ICE in New York had some form of legal status.

There’s further confusion around what ICE deems criminal behavior, too.

Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) crunches 250 million government documents every month, all in the study of US immigration patterns. A basic sift of one recent posting shows that since 2017, fewer than five percent of the people that courts are issuing orders of deportation to have committed a serious crime, while during Obama’s eight years in office that average was just shy of 15 percent.

But what exactly is a “serious” crime? According to TRAC’s co-founder, Susan Long, nobody knows what ICE’s terms mean.

Long said, for instance, crossing the border is considered a civil violation. “Under immigration law that’s not criminal activity, but that’s not how ICE defines it.” According to Long, ICE frequently changes its own rules, “And just the suspicion of criminal activity is sometimes the basis for seeking a deportation order. ICE was bad under Obama and they’ve gotten worse during Trump,” she said.

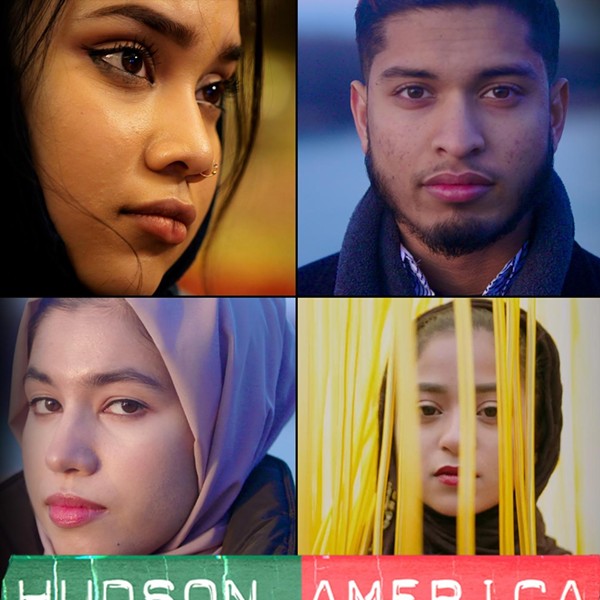

Photo by Michael Frank.

A rally in support of Luis Martinez on Main Street in New Paltz on February 16, 2019.

The Case Against Martinez

We reached out to ICE to find out the nature of Martinez’s detention. We were trying to confirm what we already learned from his wife, Tina.She explained that when Martinez and his brother Jesus were minors, their mother would bring them back to Mexico when she went home to visit her parents. This was illegal, because if you’re in pursuit of a green card, which both her boys were, you cannot leave the country without special permission. To avoid voiding their legal status, Maria Raymundo would smuggle her sons back into the US after these vacations to Mexico. On one such crossing in 1997, Martinez, then 18, was caught and deported for violating the terms of his agreement with the US government. But Tina explains that Mexico wasn’t Martinez’s home, and at the time it cost a mere $25 to hire a “coyote” to smuggle him back into the US.

In 2002, Martinez was once again deported. By then, he and Tina already had their first child, Sharia. Martinez had been working with an attorney, trying to clear up his case and get back on track to apply for citizenship, but the lawyer turned out to be unscrupulous and never alerted Martinez that ICE had called him in for an interview. Instead, the lawyer ignored the letter, and by the time Martinez knew about it, ICE’s request had morphed into a final order of deportation.

After that deportation Martinez again reentered the US illegally.

We asked ICE about Martinez’s case because we wanted to know whether the agency was first checking on his, or other detainees’ U Visa application or green card status before arrest. What exactly is their process or priority?

ICE never responded to this request, and Long said that even frequent Freedom of Information requests that seek clarity on who ICE tries to detain at jails—information the agency used to release—have been stonewalled, prompting TRAC’s most recent lawsuit, one of three pending against the agency.

Who’s a Target?

Daniel Valdez is friends with Luis Martinez and, like him, was smuggled into the US as a child. He said that what happened to Martinez is exactly what he feared would happen to him, but, unlike Martinez, Valdez began his green card process decades ago and didn’t violate it. Still, he is terrified of Trump. “The day of the Muslim ban I was like, ‘Right, they’re coming for us next.’” Valdez’s reaction was to immediately begin the process to transition from having a green card to becoming a citizen, which he’s just achieved. However, he said he still feels afraid.IDP’s Wang said that fear is no accident. “The idea is to impose constant terror,” she said. “And if you’re not yet a citizen, to make you wonder, ‘Is it safe to go to the hospital? Is it safe to take my kids to school?’ It’s very deliberate.”

And Valdez’s fear was apparently justified, because while he was still going through the final stages of becoming a US citizen, according to an ACLU lawsuit against ICE in Massachusetts, the agency was going after immigrants who were in his same situation. The suit alleges that ICE conspired with a local office of US Citizenship and Immigration Services. The latter is responsible for processing immigrants who are complying with federal law. Despite the fact that USCIS is not a law enforcement agency, the ACLU claims that in both Rhode Island and Massachusetts, couples who were appearing at offices to establish that they were married (where one half of a couple was an immigrant, the other a US citizen), were instead interrupted by ICE, and the immigrant in the couple was detained. The suit further claims that USCIS was colluding with ICE to help facilitate these arrests. This resulted in 17 detentions, according to the ACLU suit.

Besides the crackdown, another aspect of the suit shows that ICE was aware that publicity around this practice looked bad. The ACLU suit includes an email exchange between an ICE official and the USCIS office requesting widely spaced scheduling, since simultaneous arrests “has the potential to be a trigger for negative media interests, as we have seen in the past.”

ICE doesn’t like bad PR, but recent arrests of immigrants in the Hudson Valley have put the agency on a collision course with unfavorable media coverage. The Immigrant Defense Project’s recent deep dive into ICE actions at courthouses shines a bright light on these events. IDP’s Wang said ICE actions at courthouses across New York State are up 1,700 percent in 2018 compared to 2016.

The local numbers may seem less startling. There were four courthouse arrests in Ulster County in 2018, compared to one in 2017. Eight courthouse arrests in Orange County, up from zero in 2017. And 13 in Westchester in 2018, compared to four in 2017.

But each individual arrest sends ripples through the community.

In March 2017, shortly after Trump signed his executive order, New Paltz resident Joel Guerrero was detained by ICE during his regular, biannual check-in with the agency in Manhattan. The case drew national media attention in part because Guerrero is a green card holder and is married to an American.

ICE said the green card had been rescinded in 2011 because of a felony conviction for marijuana. His lawyer, Daniel Green, successfully argued that there was never any such felony, that the crime had been a misdemeanor. Guerrero was jailed for 10 weeks and was released by ICE. He still has a green card.

Joel’s wife, Jessica Guerrero, believes New Paltz residents have made a difference in his case so far. “A hundred people wrote letters and inundated our politicians’ phone lines,” she said. The activism put pressure on then Congressman John Faso as well as Assemblyman Kevin Cahill, and she believes it eventually helped lead to the release of her husband shortly before the birth of their first son. Guerrero is currently awaiting a judge’s decision on whether or not to vacate his final order of deportation and to allow him to pursue full citizenship status.

Local activism may only go so far, however.

In January 2018, then-acting ICE director Thomas Homan released guidelines for how ICE was supposed to perform its duties in and around courtrooms—and that ICE was taking these actions because, in part, some towns and cities were showing an “unwillingness…to cooperate with ICE in the transfer of custody of aliens from their prisons and jails.”

Indeed this past November, in the wake of the Homan memo, Matthew Rojas, a 23-year-old DACA recipient, was arrested by three ICE agents in New Paltz while walking with a friend to town Justice Court to plead not guilty to an October charge of possession of a controlled substance. In the wake of his arrest, Rojas’s charge was quickly reduced by the county attorney general to disorderly conduct. According to Rojas’s attorney, Mariann Connolly, ICE’s action was preemptive, because it precluded adjudication or even the chance for the sentence reduction that came after his arrest. Notably, as in Guerrero’s case and the aforementioned ACLU lawsuit, ICE does this often, detaining people and denying due process based on the premise that being in the US under tenuous legal status gives them that right.

New Paltz rallied behind Rojas, with his friends promoting twice-weekly street protests and raves at town bars Snug’s Tavern and Bacchus—the latter as fundraisers for Rojas’s legal fees. His detention was short lived, but his future legal status is tenuous. Whether he can reapply for DACA in the wake of this arrest is an open question.

As for Martinez’s arrest, reaction among those in citizenship limbo has been swift.

One local DACA recipient, an 18-year old who is friends with Sharia (and who, for obvious reasons already laid out in this piece, fears any form of attribution) said she knows the situation is “heartbreaking. Especially for Sharia’s younger siblings. They’re so dependent and used to being with both parents. This isn’t an easy separation to ease into. It’s an abrupt world-flipper.”

Her mother, who is undocumented, said she didn’t even want her daughter to know about Martinez’s arrest; she said she’s been trying to keep her daughter calm after she found out about her friend’s father. She focuses on the pragmatic rather than dwelling on the constant threats to her own family. “We are immigrants,” she said. “I work. My husband works. Our kids go to school. It’s all we can do.”

Another undocumented community member went to the February event for Martinez. He said he’s never driven to his job in Newburgh because he fears getting pulled over. He knows how to drive but can’t get a license because of his status. And while he was happy to see so many people rallying for Martinez, he said, “Every day I’m very afraid.”

The Case for the U Visa

Jesus Martinez, Luis’s kid brother, was 18 when he was murdered. It was May 9, 1999. Mother’s Day.Tina Martinez said that according to her husband, Luis, Jesus, and another man named Hector Lima had been out at a party and Luis offered to give Lima a ride home to his apartment in Newburgh. Tina said when they arrived, the three men all piled out of Luis’s car to say their goodbyes at the apartment when Jesus spotted a car racing by with a gunman leaning out of the passenger side. On impulse, Jesus shoved both his brother and Lima to the ground. “When they got up Luis looked at Jesus and realized he’d been shot through the skull,” Tina said, still profoundly shaken by what her husband witnessed.

Detective Rolando Zapata had only recently risen to working with the gang unit for the Newburgh Police in 1999. Zapata is 61 now and retired, but he described the events of the murder very clearly. He said this case “sticks in the back of [his] head,” and that he wants it solved. It’s why, though he rarely talks to the media, he agreed to discuss Jesus Martinez’s murder.

Zapata said Luis and Jesus had been out the night before the murder at the invitation of Lima. “As far as they knew this guy was just someone cool. They’d met him at a party a few weeks before,” Zapata said.

But Lima wasn’t just another guy. He was the leader of a Mexican crew called La M, and the brothers, naive to mob culture, were clueless about how much danger that meant for them.

Jesus and Luis eventually realized that the party was full of mobsters. They wanted to leave and offered to give Lima a lift home to his apartment in Newburgh. “That apartment had already been the scene of numerous attempts on Lima’s life. The rival gang wanted him dead,” Detective Zapata said.

Detective Zapata said one of the hardest moments of his career was having to visit Maria Raymundo on the Mother’s Day that her son was murdered. “I went to his house, to speak to his mother. She showed me a little gift that was still wrapped, that he was going to give her that day,” he said. “It just tore my heartstrings.”

Zapata, who has since written a letter to ICE at the request of Martinez’s attorney, said no witness to a crime ever worked harder for him during his 28-year career.

In 2000, a tip to Zapata about Jesus’s murder led to the arrest and eventual deportation of La M gang leader Lima for unlawful criminal possession of a handgun and a 12-gauge shotgun. Zapata is careful not to confirm that this tip came directly from Martinez. Zapata can’t. Jesus’s murder is still an open case—in the life of Martinez and his mother, it’s more like an open wound. And there’s a deep irony for the family that Martinez’s cooperation with Zapata helped deport the leader of a gang, and now he faces the same fate despite his help.

Sharia Martinez said her father’s detention 20 years later is a ghostly echo for her grandmother, Maria Raymundo.

“First my uncle, now my dad. It’s really hard for my grandma.” Sharia said. “It’s like she’s reliving the death of Jesus all over again.”

A Hole in the Community

New Paltz’s citizens have in part rallied around one of their own because he’s built an outsized reputation. Martinez has given broadly. He’s had an active financial and personal presence in the Chamber of Commerce, in St. Joseph’s Church, in working the Taste of New Paltz, in helping the youth basketball and soccer leagues, and in financial support of the Phillies Bridge Project, which in part donates more than four tons of food each year to Healthy Ulster to provide fresh produce to poorer community members in need. Treasurer Terence Ward said, “He told me he was quite familiar with the project and the food justice work. One year when the budget was tight he donated $1,000 on the spot.”In ICE’s eyes, however, Martinez is typical. He got a misdemeanor DUI in July of 2014 in New York City. He didn’t post bail, which would have triggered a court date, which in turn might have raised a flag to ICE about that date, giving them the chance to detain and deport him a third time.

A pending New York State law may make it harder for ICE to arrest people at court, but such a law cannot restrict community arrests; and any civil arrest by local or state police will still include fingerprinting and, likely, running those prints will ping ICE’s system.

Recently elected Ulster County Sheriff Juan Figueroa said when an entire community is afraid to testify about a crime, every town and city is at risk. “Organized crime in our country—any form of the mob—whether they were Irish or Italian, had power to scare their own people, to prevent them from talking to their own government,” he said, drawing a parallel to ICE’s intimidation tactics. “If they don’t want to talk to me and they’re a witness to a homicide, that puts us all in danger.” Figueroa said forcing people into hiding “is the lifeblood of organized crime.”

Cecelia Friedman Levin, senior policy counsel at Asista, an organization that advises immigration attorneys, seconded that assessment, saying, “The Trump Administration’s focus on increased enforcement has caused a chilling effect on survivors’ willingness to come forward and seek protection.”

The Cost

You don’t have to be an expert on immigration law, like Levin, to see what’s happening. One immigrant who has a work visa and is trying to get a green card said he is afraid for himself and his community. He lives about 20 miles from New Paltz but heard about Martinez’s arrest.“People are trying to be more quiet. They’re getting more tight. You can feel it. They won’t talk to strangers, you can tell,” he said, refusing to offer his name for the record. He thought that would be unwise, but he offered that he has a master’s degree in business administration, and so he doesn’t just look at the emotion of the situation.

“This man has actually been employing people,” he said, referring to Martinez’s Lalo Group. “He has been an active member of his community. They’ve decided to cost taxpayers money by filling jails with people rather than collecting taxes from them. Now that person isn’t paying his mortgage, isn’t funding the schools that are teaching his American kids, so now we can’t pay the teachers.” He continued, laughing ruefully, “Is this really what MAGA is all about? Economically, if you’ve been trained like me, you have to scratch your head because it’s the stupidest idea. It’s not just mean. It’s absurd.”

What’s Your Status?

Green Card: Technically a Permanent Legal Resident, with the right to work, some benefits, and to obtain full citizenship. Violating the terms of a green card, such as breaking some laws, can void your rights.Working Papers: There are multiple levels of work visas in the United States, and they vary widely in what jobs they are meant for, who can obtain them, and how long they last. As with all other levels of documentation, violating the law, and/or travel outside the US without special permission, can void your visa.

DACA: Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival was an executive order established by President Obama in 2012. It allowed some people who were under 31 on June 15 of that year to apply. Additionally, you would have had to arrive in the US before the age of 16 and had continuously resided in the US since June 15, 2007. There are further rules around education, military status, and other factors. Committing certain misdemeanors or a felony can cause a DACA recipient to lose those protections, including the right to work and having a driver’s license, and such a crime would also put them at risk of deportation. While Trump rescinded DACA September 5, 2017, barring new applicants, that order has stalled in federal court, so current DACA recipients can still renew every two years.

Undocumented: Anyone who is not legally residing in the US. Although the recent surge at the US-Mexico border may eventually change the makeup of who is in the US without some form of documentation, according to the Center for Migration Studies, the vast majority of undocumented residents in the US arrived by plane and overstayed their tourist, work, or education visas.

The reporter, Michael Frank, was subsequently able to speak to Martinez on the phone. Read follow-up story.