On November 3, 2022, Magda Sharff, a student at Vassar College, took the bus from campus to the Dutchess County Supreme Court to attend an administrative hearing. She wandered the building alone, dealing with questions from a journalist she encountered in the hallway, before finding the right room. Though intended to be a quick hearing, the process took several hours, mostly due to the defense counsel’s tardiness. Sharff remembers him coming in extremely late, looking disheveled and grumpy from getting off a plane. “The actual defendant, Erik Haight, the Republican Commissioner of the Board of Elections, showed up with a book of election laws, a map of the county, his glasses, and a face mask, and he put those things down on the table and then he left and never came back,” Sharff says.

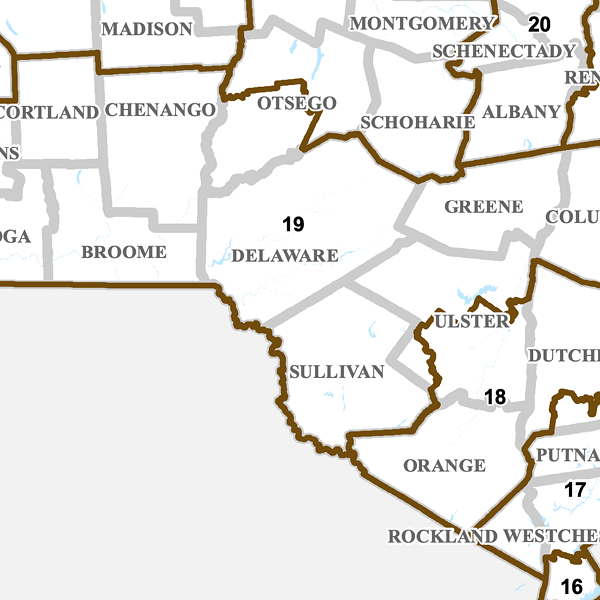

The purpose of the hearing was to decide whether Vassar College would have its own polling site for the 2022 election. At the time, students were spread between multiple different polling sites based on where they lived on campus. Yet, the battle at Vassar was just one part of a larger struggle for student voting rights in the Hudson Valley.

In the late 1990s, Jonathan Becker, current director of the Center for Civic Engagement at Bard College, realized that a Dutchess County election questionnaire barred voters who identified themselves as students. This discovery launched a series of successful lawsuits by the college to protect student voters from 1998 to 2012. Their next challenge was to establish an accessible place for students to vote, leading to Bard’s fight for an on-campus polling site in 2020, which ultimately inspired New York Election Law 4-104. This provision, which was enacted in 2020 as part of the state budget, requires all college campuses with at least 300 registered voters to have an on-campus polling place and also ensures that campuses cannot be broken up into multiple districts.

When Bard attempted to move a polling place to campus that year, a judge told them that it would not be possible. The judge’s decision was informed by Republican Board of Elections Commissioner Erik Haight’s advice that altering the plans could confuse the district’s voters. The very next day, however, the Board of Elections moved the site for Red Hook’s districts 7 and 8. Erin Cannan, deputy director of the Center for Civic Engagement distinctly remembers sitting on a Zoom call hearing and watching the look of betrayal on the judge’s face when she realized Haight had misled them. Judge Maria Rosa wrote in her statement, “Apparently there was, and is, time to move the polling place for District 5 in Red Hook.” With this evidence, the court reversed its initial ruling and decided in favor of Bard.

After the judge’s decision, on a hot fall day, Cannan gave the election commissioners a tour of the campus in order to choose a building for the polling site. At the end of their day, the commissioners suggested one more option: the one Bard administrative building located across Route 9G, a busy road on the edge of campus. Cannan says the encounter “was so clearly an attempt to find the most inconvenient site on campus,” adding, “it was like watching voter suppression at work.” Ultimately, they reached an agreement with the election commissioners to use Bard’s Bertelsmann Campus Center as the on-campus polling site.

Absentee Voting = Lower Voter Turnout

With over 1,000 voters on campus registered locally, Vassar students and the administration were eager to take advantage of the new election law and establish their own polling site. Rebecca Edwards, a Vassar history professor and former county legislator, stressed the importance of accessible polling sites, pointing out that, “Any group of voters that predominantly vote absentee is going to have a lower rate of participation just because of the steps and hurdles.” Prior to 2022, Vassar students registered to vote on campus faced several barriers to easy, in-person voting. The college relied on two different off-campus polling sites: one at a Methodist church on busy Route 376, and one at the Wastewater Authority in Arlington. The campus was also split up into three local districts, meaning moving dorms from year to year might also mean moving districts.

The statutory deadline for the county to designate a site for Vassar’s campus was August 1, 2022. But as that deadline passed with no action from Dutchess County, people took notice. On October 25, the Dutchess County Student Voting Coalition, the League of Women Voters, Democracy Matters, and the Andrew Goodman Foundation joined forces to write a letter to the county. They pointed out that because Commissioner Haight was unresponsive to repeated requests for action on establishing a polling site at Vassar, he was violating the law. (In New York, all Board of Elections are led by one Republican and one Democrat who must collaborate in order for the board to function, so even though Democratic Commissioner Hannah Black was in favor of the site, nothing could move forward without Haight.)

"The more that I learned about it as the case went on, the more I realized the reason we didn’t have a polling place on campus was that the county was trying really hard to suppress young voters.” —Magda Sharff, Vassar student

tweet this

The League of Women Voters of the Mid-Hudson Region took the next step by filing a lawsuit. Seeking student involvement, Prof. Edwards sent out an email to all students registered to vote on campus asking them to sign on as affected parties. Magda Sharff was the only one to respond, making her the sole student plaintiff. The other plaintiff alongside Sharff was Taniesha Means, a political science professor.

Though interested in helping out, Sharff was taken aback when she realized she was agreeing to participate in a court case. Soon enough, she started getting calls from lawyers. The calls multiplied, with reporters calling her at work, at choir rehearsals, or during class, demanding she send a photo of herself to Fox News. Though initially overwhelmed, Sharff says, “I did care about it a lot, and the more that I learned about it as the case went on, the more I realized the reason we didn’t have a polling place on campus was that the county was trying really hard to suppress young voters.”

During the November 2022 hearing, the arguments Haight’s lawyer presented were that Haight was not served the case in person, that Vassar College needed to be and interested party, and that the case was presented too late. Jennifer Clark, attorney and League spokesperson, was able to deconstruct each one of these points as a non-argument, citing the fact that the League had gotten permission from a judge to serve the case electronically, and that Wesley Dixon, special assistant to the president and secretary to the Board of Trustees, had released a statement demonstrating the College’s support for the polling site. Clark explained that Haight’s absence from the hearing was actually to avoid giving the League the opportunity to serve him the case in person. Yet his absence meant that there was no one to rebut Democratic Commissioner Hannah Black, who supported a Vassar polling site, and Judge Christie D’Alessio decided in the League’s favor. Black also speculated that Haight did not testify to avoid a potential repeat perjury offense, which he committed in the 2020 Bard case.

At 5 pm on the Friday before election day, Haight submitted an appeal. Clark remembers that weekend as full of intense stress and disappointment. “We were on pins and needles waiting to hear what was happening,” she says.

The League lawyers were able to get through to the court over the weekend. On Monday, the Judge reaffirmed that her initial ruling was sufficiently clear and that Haight could be held in contempt of court for not complying. In less than 24 hours, the polling site was set up in the Aula, an event space on Vassar’s campus, with extra voting machines taken from other sites. “It was quite a rush, but the Democratic side was on the side of following the law and in compliance the whole entire way,” Commissioner Black says. “It could’ve been much simpler than it ended up being if my counterpart had decided to follow the law and not ignore it.”

On Election Day, Sharff walked over to the Aula from her dorm at seven in the morning, making her the first person to vote there. “It felt really nice, after having sat through that hearing and having all the stressful phone calls, knowing that it was actually serving a purpose and students were actually going to be voting at that polling place,” she says.

Yet after the case Prof. Means was left wondering, “How do we hold [Haight] accountable?” Though happy with the end result of Vassar’s fight, she questioned why it needed to be such a struggle and pointed out that what Haight did was obstruction of justice. She felt like she had experienced firsthand the “lack of teeth” judges have when it comes to enforcement.

Younger Voters Lean Democratic

In Dutchess County, election commissioners must be appointed by their party and then confirmed by the county legislature. Haight has been the Dutchess County Republican Election Commissioner since 2011 and still holds the position. Black points out that because Haight did end up complying in setting up a polling place, even if it was at the very last minute, he cannot be held in contempt of court. In order to pursue further legal action against him, election law would need to be clearer on proper timelines for establishing polling sites.

The common arguments against allowing students to vote at their college are that they are transplants who don’t pay taxes and don’t truly belong to the community, and therefore shouldn’t vote. Prof. Means rebuts this claim. “There is no asterisk in the Constitution,” she says. Prof. Edwards adds that young people are generally transient “If we assume that people have to live in a place for years and years and years in order to deserve the vote and belong there, then people are going to get disenfranchised,” she says.

She and others involved in the case also point out that students contribute to the local community through volunteer work, shopping, and using public transportation. So why is it that students are valued when it comes to their participation in the local political economy, but not when it comes to their vote? Prof. Means answers this question by arguing that Vassar represents a pattern of contestation over college student’s voting rights by people who are afraid of how they might vote. In February 2023, Texas Republican state legislator Carrie Isaac proposed a new bill that would prohibit polling sites at colleges and universities in the state. In March, Republican lawmakers in Idaho banned student IDs as a valid form of voter identification, joining North Dakota, Ohio, South Carolina, and Tennessee.

“If young people understood the power they had, they could flip everything."—Kenya Gadsden, County Clerk candidate

tweet this

This fear of the power of the student vote may be influenced by recent data on youth turnout at the polls. The Tufts Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement estimates “that 50 percent of young people, ages 18-29, voted in the 2020 presidential election, a remarkable 11-point increase from 2016 (39 percent) and likely one of the highest rates of youth electoral participation since the voting age was lowered to 18.” With younger voters often tending to vote Democratic, Republicans fear that this uptick could hurt their party’s success.

Looking at last year’s election results, Tufts reports that New York was one of only a few states that had higher youth voter turnout in 2022 than in 2018, hitting 20.7 percent, which may have contributed to Democratic wins in statewide races for governor and US Senate. The Tufts report also points out that election policies matter, stating, “Many of the states with the highest youth turnout have policies like automatic and same-day registration that make it easier for young people to register and vote. Many of the states with lower turnout do not have these policies in place or have restrictions like voter ID laws.”

Calder Beasley, a Vassar student dorm voting advisor for VassarVotes, sees this idea in action on campus. “When I can tell a student that all they have to do on Election Day is wake up and walk to the Aula and vote, they are number one, more likely to vote, and number two, more likely to get registered to vote in Poughkeepsie because it sounds easier than sending in a mail in ballot to their home state,” he says.

“We Had to Fight Like Hell”

On November 7, Vassar students will again have the chance to cast their votes on campus, as all Dutchess County residents make their way to the polls. Since 2023 is an off-year election, many positions on the ballot are local, including district attorney, town supervisor, county legislator, and executive.

In advance of the election, Vassar Voices for Planned Parenthood (VVPP) held a candidate panel on October 25, and though all candidates were invited, all attendees were on the Democratic ticket. Candidates encouraged students to get to the polls and have their voices heard, no matter who they vote for. “If young people understood the power they had, they could flip everything,” said Kenya Gadsden, a candidate for County Clerk. “This is your election to win or lose,” Jim Rodgers, a Family Court Judge candidate.

Dutchess County is a swing county, so elections are often very close. In 2021, Edwards lost her seat as County Legislator by 43 votes. “If my hall voted, we would change that. The Republicans are scared of us because we can put Democrats in power as a student body,” says Maggie Greenberg, VVPP co-communications chair.

Aware of Dutchess County’s designation as a political battleground, Sharff comments, “it feels like [Republicans] care so much because they know that if all of us vote, we’re going to break some kind of tie or influence the politics here, which really goes to show how contested the district is.” Prof. Means echoes this: “Despite this law, it wasn’t going to happen easily, and we had to fight like hell for it.”