Jessica Walker was frustrated. It was mid-March, in the early days of New York State’s coronavirus lockdown, and the 33-year-old teacher’s aide had dragged her 10-year-old son and her infant boy to a grocery store in New Paltz. The store was crammed with panicked shoppers. Walker had loaded the belt with her purchases, only to find out her Electronic Benefits Transfer card, which is used to access Women, Infants, and Children benefits, wasn’t working.

Because her job pays so little, Walker needs the food assistance. “The cashier was telling me that none of my purchases went through, then they’re calling over the manager.” Walker describes the scene as embarrassing, with the manager confronting her, saying that Walker didn’t know how her card worked, then belatedly correcting herself and apologizing, explaining that perhaps the problem was with the store, or maybe with EBT’s system. Walker was told there was no way to fix the issue; she’d have to leave empty-handed. Later, Walker called an EBT helpline, only to get voicemail and no actual help.

“It creates shame,” Walker says.

From the remove of a few months, Walker is able to chuckle, albeit with a bitter tinge, about clawing through yet another tangle of red tape trying to feed her children. “I’ve been working at this way before COVID-19,” she says. She recalls living through worse: Having a college degree cleaves her, at least intellectually, from her family’s past, at times being homeless and sleeping in her mother’s car when she was a child. “I’m blessed to have a full-time job, a home, connecting with sweet souls” at the middle school where she’s employed.

Still, navigating the benefits maze can feel endless even during normal times, and the societal fracturing of the pandemic has exposed how perilously close to food insecurity many of us live. Don’t forget: Just a few short months ago, we had record low unemployment nationwide. It was 4.1 percent in Ulster County in March, then leaped to 14.9 percent in April. But even when most people had a job, too many were just scraping by. The poverty rate in Ulster County is about 14 percent, slightly worse than the lower and mid-Hudson Valley average. Drill deeper, and more than 40 percent of families in Ulster County are struggling to make ends meet, according to a broader United Way measure that looks at the true cost of living.

“It’s exhausting,” sighs Walker. “If you don't have tough skin, you would much rather go without.”

Two Startups on a Mission

Going without is exactly what Ulster County Executive Pat Ryan feared would happen to too many families in mid-March. Like Walker’s older son, 46 percent of kids in Ulster County get some form of meal assistance in schools, and districts throughout New York State were thrown for a loop when Governor Andrew Cuomo suddenly reversed course on March 16 and ordered all schools closed statewide. Up to that point, Cuomo had waffled on switching to online-only teaching, at first signaling that too many children depend on the K-12 system for meals, just as working parents depend on schools as de facto daycare.

Ryan’s most immediate concern was Ulster’s 10 school districts, where in 2018 more than 10,000 children received school breakfasts and lunches. Without kids in classrooms, the county would have to untangle which parents could drive to schools for meal pickup—or who, perhaps, couldn’t, out of fear of exposure to the virus, or because they were still working.

In early March, once word circulated that Cuomo was weighing a statewide shutdown, Ryan huddled with several of his deputies in a group headed by Assistant Deputy County Executive Tim Weidemann. “That was about the time we’d stood up a COVID-19 hotline,” Ryan explains, saying that within just a few days, “we had this unbelievable volume.” Callers were trying to find out how to get tested, but also, “People were asking, ‘How am I supposed to eat?’ There were seniors afraid to leave their homes, people that were starting to get laid off and they didn't have money.” Ryan knew then “what we had [for feeding people] probably wasn’t working very well before and was definitely not going to hold up during COVID.”

Of course, the problem of food insecurity isn’t limited to families with children—it also impacts adults, especially older ones, and the practical problem of affording adequate food is often compounded by emotional distress at not being able to meet this most basic human need, as well as the shame Walker mentioned.

For this article, I spoke to several senior citizens in line at various food pantries around the region who preferred to remain anonymous. One woman says she was paranoid about having identifying details published. She says she wasn’t ashamed to receive help—then admits that she didn’t want friends to know. It’s a story I heard frequently.

Amanda LaValle heads the Ulster County Department of the Environment, a tiny group of five employees. Last fall, her team updated its plan for responding in the event of a natural disaster. That plan also inventoried existing relationships throughout the county, from town supervisors to “food pantries and community partners,” so that the team could pick up the phone and create a response network in short order.

Ryan tasked Deputy County Executive Evelyn Wright and Lavalle with converting that study, dubbed Project Resilience, into a game plan in a matter of hours in the early days of New York’s lockdown. He says it was “like building the plane while flying it through a storm with, you know, a trainee pilot.”

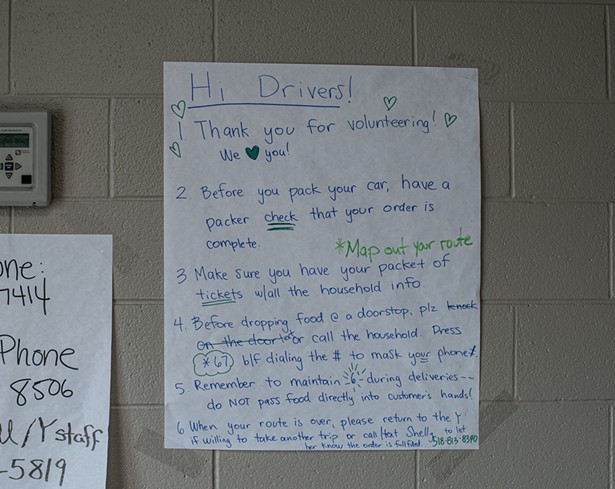

The idea for Project Resilience in those early weeks was deceptively elegant. The county paid restaurants $10 a meal to cook for those in need, offering restaurants a financial lifeline and the ability to keep staff employed while they awaited word on receiving a loan from the federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program. Ultimately 159 restaurants participated in Project Resilience, cooking meals that they’d courier to distribution points in each of the county’s 24 municipalities. From there, local leaders, such as town supervisors, made calls to muster volunteers who could drive the food to recipients’ doorsteps. Meanwhile, hundreds of people were ringing the county’s hotline, not only for assistance, but also to offer help. Eventually the volunteer army swelled to over 600 people, making it possible to deliver thousands of meals per week.

That outpouring of support still stuns Ryan. “We saw our interconnectivity and community and humanity,” he says. LaValle believes she’ll be studying the way the community came together and government sprang to action for the remainder of her career.

The city of Kingston—the county seat—had its own parallel problems, according to Dr. Paul Paladino, the superintendent of the Kingston School District. Pre-COVID, the vast majority of the district’s 6,500 kids “didn’t bring a bagged lunch from home,” he says. Instead, they were on partial or total meal assistance for both breakfast and lunch. Even though the district still had the ability to make meals while schools were closed, they couldn’t get them to students. The district couldn’t convert school buses to a delivery service because it subcontracts busing to a private company, and that company sacked its drivers when schools shut. (Subsequently and at great expense, the district purchased 10 refrigerated trucks to shuttle food to parts of the district with the most intense meal need, and will continue this program at least through the summer.)

To meet the need for a delivery mechanism, a city-level analogue to Project Resilience sprang to life in Kingston. The Kingston Emergency Food Collaborative involved 14 community organizations, ranging from established public-private nonprofits like Live Well Kingston to organizations better known for intellectual programming, like the AJ Williams-Myers African Roots Center, to People’s Place food pantry and Family of Woodstock’s Hodge Center. The latter two were crucial, because they already have an established trust for feeding the community—and commercial kitchen infrastructure. These groups teamed with the schools to help handle delivery, and the YMCA loaned its facilities, including walk-in refrigeration.

Both Project Resilience and the Kingston Emergency Food Collaborative benefited from the generosity of city and county governments. Both loaned employees to the work, at full pay. That included experts, like geographers who could “live” map calls to the hotline so that driving routes could be tweaked, constantly adding deliveries to densely packed circuits so drivers—all volunteers, and some also recipients of the food aid themselves—wouldn’t waste time and fuel driving all over town.

Jeff Benjamin is 53 and lives just outside Woodstock. He was one of several volunteers interviewed for this story who said they were struggling to make ends meet even before the crisis.

In mid-April on a sunny morning, Benjamin, wearing a mask and gloves, signed in to volunteer at the YMCA. He got in line as a column of drivers pulled into a loading area, where a sea of volunteers jammed hatchbacks, sedans, and minivans with stacks of packaged meals to haul to stoops and doorsteps all over town. Benjamin drives an old rusted Pontiac, which he topped off with coolant before plying the route.

Benjamin, like Jessica Walker, isn’t who you’d expect would sometimes need food assistance. He’s getting his PhD from Columbia, but he visits food pantries in Ulster County because he’s paid very poorly. He says this was his fourth time driving for the Collaborative, and framed the effort as his way of giving back. “You just need one little gesture of kindness in your day. No matter how badly it’s maybe going, that ‘hello’ or knock says someone’s caring.”

The Reckoning

By the middle of May, between the two efforts, there were over a thousand “Jeff Benjamins” volunteering. Their collective output allowed Project Resilience to deliver 135,149 prepared meals, and by the middle of June, 106,983 meals as groceries. The Collaborative delivered 57,380 hot meals and tens of thousands of bags of groceries through three central hubs in Kingston: People’s Place, Ulster County Community Action, and Catholic Charities Food Pantry.

There were a variety of reasons people needed food assistance, according to a county survey tabulated from all of the calls to the Resilience hotline. Fully half said they weren’t broke, but were immunocompromised and feared exposure to the virus if they went shopping. About one-quarter said they’d been fired due to the pandemic or weren’t getting public meal assistance. Over 10 percent said they lacked childcare.

And although the initial motivation for both efforts was to feed people, this formula of relief also helped stall the spread of COVID-19 in the region, possibly saving hundreds of lives. Especially since, in early April, Ulster County came very close to running out of ventilators and ICU beds for critically ill patients.

By all measures, these efforts were astonishingly successful. So why have they all but entirely stopped?

Because, quite simply, both programs tore through the same finite pile of cash, a $2 million grant from the NoVo Foundation, a local organization that focuses on economic, racial, and systemic injustices. That money had originally been allocated to a county effort called Brighter Futures, meant to alter the continuing cycle of poverty by assigning mentors and trainers as well as funding to at-risk children and to their families. Once Ryan saw the oncoming crunch of school closures and hunger, he reached out to NoVo to ask if they could divert Brighter Futures grant money to this more pressing and dire cause. NoVo immediately agreed. That same source was used by the Kingston Emergency Food Collaborative as well, to reimburse restaurants, with checks written through an avenue the city had used before, the United Way, which is used to compensating private vendors more quickly than a lumbering government bureaucracy.

However, NoVo’s role was actually larger. Emily Flynn, Director of Health and Wellness for the City of Kingston, also runs a department called Live Well Kingston, which in part aids food insecurity—and which Flynn notes, was stood up via a grant from NoVo.

“Novo also helps fund so many organizations, from Family of Woodstock, to the [Hudson Valley] Farm Hub, that were involved in the Collaborative, and a great many of these organizations had the capacity to volunteer to do this because we were also able to keep our regular jobs,” she says. “It shows you what amazing things can happen when there’s community funding.”

The county and the United Way together collected an additional $200,000 through private donations. In the long run, however, it was not enough to offset a daily county “burn rate” that was cresting $40,000 a day by the end of April.

The all-volunteer labor force was also showing cracks by then. Some volunteers were going back to regular work. And many people in the Collaborative were working 16-hour days, six days a week, trying to keep the wheels on the machine they’d made. All that capital, human and literal, eventually ran dry, leaving the people who had come to rely on this support with fewer alternatives. The response, ramped up to meet the demands of the emergency, simply wasn’t sustainable at that rate, even though the needs it met didn’t disappear when the money dried up. If anything, with so many more jobless, and emergency SNAP benefits about to pare down, county officials are deeply worried.

The Collaborative may have slowed, but it didn’t totally shut down—a small contingent of folks have kept it going, delivering some 40 prepared meals per day out of Family of Woodstock’s Hodge Center, and providing groceries to around 100 households per week out of People’s Place.

The Before and After

On a hot day in early June, a meandering queue was forming at 10am at People’s Place in midtown Kingston. The food pantry and thrift store is a fixture in the community, dating back five decades. The line was for their weekly farmers’ market, where anyone in need can get fresh produce for free.

But it didn’t feel like a farmers’ market. This queue felt like what it was: A breadline. People didn’t want to chat with a journalist. Patrick, a “mid-20s” nurse’s associate, didn’t mind talking, as long as I didn’t use his full name. This was his day off. He’d been working 80-95 hours a week since COVID hit, and despite that sheer volume of hours, still didn’t earn enough. “This helps me make ends meet,” he notes. Rose Brennan is “of retirement age,” and pre-pandemic, would make extra income at crafts fairs. “I don’t have enough to retire. I’ll have to work till I drop.” Brennan was grateful for the assistance, but she also grumbled that every pantry had its own red tape. Here, you show your ID, to prove you haven’t “been fed too much,” in Brennan’s words.

People’s Place director Christine Hein knows food banks are the backbone of crisis response. “A crisis is personal, usually," she says. “It’s cancer. It’s a divorce or unexpected death. Everything’s okay, then your whole life is turned upside down.” People’s Place will also continue to provide noncrisis response throughout the summer in the form of 60,000 supplemental meals as school lunches, a program that will augment some school districts’ own summer school lunches.

Katrina Light, Community Food Program Manager at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub, credited Hein’s tireless efforts throughout the crisis, quickly converting People’s Place from a food pantry to food-prep and delivery system. Light was part of the Collaborative’s team responsible for distributing groceries. Today, however, she fears the unintended consequences of creating a support network that the Collaborative and Ulster County had to quit. “Now we’re part of that story of letting people down.” Light’s not critical of the response. Like County Executive Ryan, she says it had to be done, and is tremendously proud of the work.

However, she echoes something Ryan said, when she notes that volunteers working the hotlines started to get calls about mental health or other health needs. “We’re not social workers,” and yet some of what she and her team were hearing needed that level of response.

Ryan says part of his government’s learning process in the wake of the coronavirus and the Black Lives Matter marches is to think about how hunger maps over broader need. “We can’t just let ourselves snap back," he says. “We celebrate treating opioid addiction inside jails. What? How about before jail ever happens? If we don't take away broader lessons of systemic inequalities, then shame on us.”

One such initiative will be the new Ulster County Recovery Service Center, which Ryan characterizes as a one-stop shop for county residents seeking answers on everything from COVID testing to food assistance to accessing help with mental health or addiction.

It’s a nice idea, but Jessica Walker, the New Paltz teacher’s aide, wonders how to erase old scars. She says she never even bothered to sign up for Project Resilience. Calling the hotline led her down a rabbit hole where she got asked a litany of personal questions. Memories of past assistance deadends started to bubble up in her head, which have taught her not to trust a system that may not believe her need is genuine.

Pat Ryan is aware of that problem. At the height of Project Resilience, one town official whom he won’t name told Ryan he feared people might get too much food. “Do you understand the courage it takes to ask for help?” Ryan asks. “And then to be met with suspicion?”

Walker says that lack of trust is at the root of the problem. “It’s like, ‘How dare you get this low in life.’” But she’s not without hope. She believes if an effort was made to not just give her and her kids a day’s food, but to give her a stake in helping themselves, that could radically change the equation. “I have a college degree. But if you just see a single black woman with two children, you just see a stereotype. Nothing in that stereotype says you need what we know—our intimate knowledge of navigating the social safety net—but that’s what you need. People like me.”

Correction: This story previously stated that the Kingston Emergency Food Collaborative shut down. That was the plan at the time of reporting, but the Collaborative was able to keep operating in a smaller capacity. The story was updated to include this information on July 28. Readers can sign up to volunteer to help the efforts at this link. If you need food assistance, you can call (888) 316-0879 or visit kingstonemergencyfood.com.