Last September a reporter from Bronx-based cable TV station News 12 showed up in Newburgh to talk to town police lieutenant Adam Zeilberger. She wanted to know more about the police department’s weekly “Warrant Wednesday” Facebook posts, in which the department posts names and photos of people with open arrest warrants.

Zeilberger gave a startling statistic: since the launch of bail reform the department had seen a 40-percent increase in open warrants for failure to appear in court. “It’s basically a catch and release,” he said.

He didn’t say the warrant numbers increased because of bail reform. But in a tweet about the story the reporter filled in the blank: “Town of Newburgh police say the open arrest warrants for the department are up 40% due to bail reform.”

New York’s bail reform law went into effect in January 2020, eliminating bail for lower-level crimes. But New York Democrats have twice weakened it, scared off by a national spike in certain categories of crime starting in 2020 and a disastrous showing in the 2022 elections after Republicans successfully pinned the increase to the reform.

Under New York law bail has one purpose: to incentivize people to return to court after an arrest. In its simplest form it works like this: a person who gets arrested comes before a judge, who sets an amount they have to pay if they want to be released before their trial. If they pay they can go free, and if they show up for their court appearances they get their money back.

But people who don’t have the money stay behind bars, meaning that before bail reform thousands accused of low-level crimes were locked up only because they couldn’t pay—60 percent of the state’s jail population in 2019.

Now Kathy Hochul is locked in a budget battle with Democratic state legislators, mostly over her proposed further rollbacks to bail reform. There’s no evidence that taking another plank out of the law will have any effect on crime—a new study indicates the opposite. But those who oppose the ongoing unraveling of reform are at a huge disadvantage—stories like the one in Newburgh drive public opinion, and the people the reform law helps don’t want to tell their own stories.

Between 2019 and 2020 some categories of crime–murders, assaults, and car thefts–rose nationally. There’s no evidence bail reform caused New York’s own crime spike; crime went up both in states that had enacted reform and those that hadn’t. FBI crime data show that New York’s 2020 violent crime rate was 10 percent lower than in the US as a whole and 23 percent lower than in Texas, which is going the opposite direction on bail. (2020 is the latest year of FBI violent crime data.)

Similarly, New York’s burglary rate in 2020 was about half that of the country and less than half that of Texas. Midway through 2020, the Texas city of Lubbock may have been the US murder epicenter, up 105 percent from the year before.

That’s not stopped news outlets from repeating police claims that bail reform is driving up crime. In February, the Yonkers police department tweeted a video of shoplifters strolling out of a store with merchandise, which was picked up by Middletown radio station WRRV. “Dear New York State Legislature: bail reform has degraded the quality-of-life in our region and led to an increase in crime and lawlessness,” read the department’s post.

The governor wants to roll back a key element of the law: its requirement that judges use the “least restrictive” method to ensure a person’s return to court. In a March 22 speech, Hochul cited data from a recent John Jay College study and elsewhere to argue that “for violent felonies, we are seeing an uptick in recidivism–people reoffending while they're out and even bigger increases for recidivism for defendants with serious crimes.”

Both the Republican and Democratic candidates for Ulster County district attorney–Michael Kavanagh and Emmanuel Nneji—told The River they support that change. “[Removing] the least restrictive standard, if that's actually what the governor and the legislature decide to do, would presumably return the discretion to the courts and the judges,” says Democrat-endorsed Nneji. “That discretion, I do not think, should have been taken away to begin with.”

Democratic state legislators say the change will undermine the intent of the law by giving judges leeway to set bail more frequently and in higher amounts. Individual judges will behave differently in cases with identical circumstances, wrote two legislators in a March 27 op-ed.

Laurie Dick is a Legal Aid Society defense attorney who lives in Beacon and practices in Brooklyn. Months ago, a judge ordered one of her clients jailed before trial, giving him no option even of posting bail. She filed a writ of habeas corpus with another judge to review the case, arguing that that jail wasn’t the least restrictive option to ensure his return to court.

She won, and he posted bail and was released. Since then he’s shown up to all his court appearances for 15 straight months, she says. He’s getting programming and supervision to help him stay on track, including talk therapy that for the first time is helping with his PTSD, which is at the root of his substance abuse and mental health issues.

“If there is no guiding language like least restrictive means, then no writs–I don't see any writs being granted,” says Dick. “The judges will just say, I agree with you, Ms. Dick. I agree that this was not necessary but I have no legal authority to change what that judge did.”

Removing the least-restrictive standard also will invite even more racial bias into judges’ decisions, say bail reform’s defenders. Even after reform, in counties outside New York City 66 percent of accused people sent to jail before their trial were Black or Hispanic, triple their representation in the population, according to an April 2022 report by the Brooklyn-based Envision Freedom Fund.

The River asked Hochul’s press office for the source of her data on rising recidivism for those charged with violent felonies. The John Jay study that the governor cited concluded just the opposite–for those charged with a violent felony and released post-bail-reform, rearrest rates two years after the initial arrest were slightly lower than rates for those charged with a violent felony who had bail set or were jailed before trial.

Hochul spokesperson Maggie Halley responded with a written statement: “Governor Hochul’s Executive Budget makes transformative investments to make New York more affordable, more livable and safer, and she continues to work with the legislature to deliver a final budget that meets the needs of all New Yorkers.”

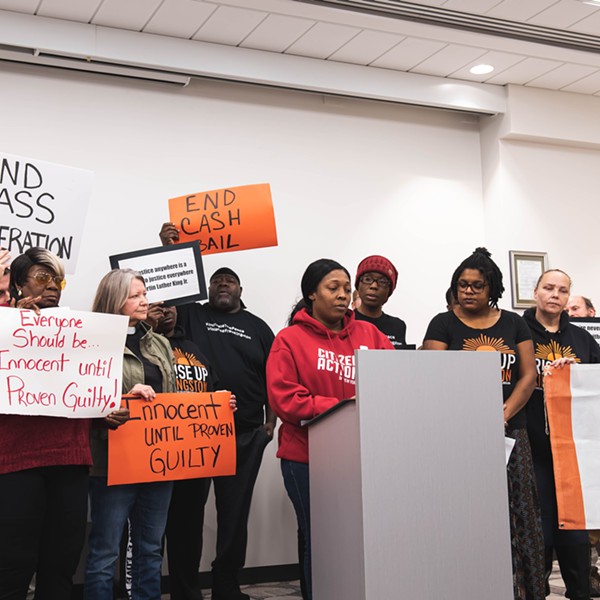

New York Democrats lost last fall on crime because they defended bail reform but didn’t champion it, according to a late November Politico analysis. The numbers indicate there could be much to champion. A February report by the national advocacy group FWD.us concluded that in the two years after New York’s law, 24,000 fewer people had bail set in their cases, people accused kept $104 million that they would have paid in bail, and defendants spent 1.9 million more nights at home instead of in jail.

But getting the people who benefit from reform to tell their stories–which has more impact than numbers like those—remains a challenge.

No one wants to be the public poster child if they’ve been accused of a crime even if they’re ultimately found not guilty, Susan Bryant of the New York State Defenders Association told state legislators at a hearing in January. “The reason that you don’t hear [these stories] more is because they’re individual people who don’t want to air their situation to the public,” she said.

“The success stories,” added Yung Mi-Lee of the New York State Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, “are just unquantifiable”—people released who went on to get jobs at law firms, college degrees, and housing and treatment.

On the other side are police departments like Newburgh’s that can attach names and faces to cases in which a person arrested and released goes on to commit a crime or not show up in court.

The News 12 story in Newburgh was one of the few blaming bail reform that included specific data—that startling 40-percent rise in warrants for failure to appear in court since reform. The statistic is out of keeping with state and county data: statewide, after bail reform, accused people were about four percentage points more likely to show up for court appearances than before–88 percent after versus 84 before, according to state data. In Orange County 87 percent of people released have shown up to court since the start of bail reform.

The River contacted Zeilberger for the department’s underlying numbers. Indeed, in 2020 the department issued 154 warrants for failure to appear in court, which more than doubled to 394 in 2021, a 156-percent increase. (Zeilberger says he’s not sure where the 40-percent figure came from.)

But in 2019—pre-bail reform—the total was 389. So the actual increase in failure-to-appear warrants from 2019 to 2021 was a little more than 1 percent. The 2022 numbers are on pace to hit 306 once the full-year’s data comes in—a drop of 22 percent.

Would it be fair to say that these data don’t show that bail reform caused a rise in the number of people ignoring their court appearances? The River asked Zeilberger.

“On the lower level offenses… we're finding that more and more and more, you know, time and time again, when these defendants are getting cut loose with appearance tickets from the police station, they're not coming back to court when they're supposed to and then they're getting warrants issued for them, and then they get rearrested,” Zeilberger responded.

But why isn’t that showing up in his department’s numbers?

“I could try calling up to the court to see if they track that data,” he said.