A look at recent national media coverage of the Mid-Hudson Valley reveals a common theme: youthfulness. The prevailing narrative—that young people are migrating north from Brooklyn and spurring a creative renaissance from Beacon to Hudson—may be partially true. But it also ignores the fact that this region is aging, rapidly and profoundly.

A report published in October, “Out of Alignment,” by the Newburgh-based think tank Hudson Valley Pattern for Progress, suggests that the Mid-Hudson Valley has arrived at a crossroads where demographics and the economy are misaligned. Some of the most striking statistics pertain to older residents. For example, adults 55 and older are projected to comprise 35 percent of the region's population by 2030, a 17 percent increase from 2017. Adults 75 and older will make up 10 percent of regional residents. And already, the median age in six out of the seven Mid-Hudson Valley counties surpasses state and local averages.

“This is just the baby boomers coming of age,” says Pattern for Progress’s CEO and president, Jonathan Drapkin.

Members of the Silent Generation?—the demographic cohort preceding the boomers?—are also living longer than ever, and the aging is happening statewide. The older adult population (which refers to adults ages 65 and up) is growing faster than the overall population in New York’s 20 largest cities and counties, according to a 2019 report by the Center for an Urban Future. Moreover, that report noted that the Mid-Hudson Valley is home to two out of the three New York State counties with the greatest increases in the 65-plus population over the past decade: Orange and Dutchess. At the same time, the 85-plus population of Dutchess County increased by 80 percent, the largest increase of that population in any county statewide.

These findings portend a spate of challenges across the region, from providing healthcare and affordable housing for seniors to creating opportunities for employment, according to Drapkin.

“The impact may not have been as striking had the Valley been growing at a healthy rate, but it’s not [been],” he says.

A Dwindling and Aging Population Faces Rising Costs

People are moving into the study area—the Mid-Hudson Valley saw a net gain of 5,674 residents from New York City between 2015-2016—and there’s anecdotal evidence of young people relocating to Poughkeepsie and Kingston. But Drapkin says he won’t be convinced until 2020 census numbers come in; all Mid-Hudson Valley counties but Orange saw a population decline between 2010 and 2017, the latest year for which data is available. According to the Pattern for Progress report, deaths out-paced births in Ulster, Columbia, and Greene counties in 2016, and the regional fertility rate fell to 1.76 that year, just below the national rate of 1.8 and significantly lower than the 2.1 rate needed to maintain a stable population. And not enough people have been moving in to make up the difference.

That uncertainty around population growth is what sets the Mid-Hudson region and much of upstate New York apart from places like Westchester, Long Island, and New York City, where populations are growing more robustly and aging simultaneously, according to Drapkin. And the low or stagnant population growth in the Mid-Hudson Valley seems likely to continue in the coming decade: 76 percent of Gen Xers and 64 percent of baby boomers in Dutchess County said they’re at least somewhat likely to leave New York State during their retirement, according to a 2015 AARP survey. Moreover, Pattern for Progress projects a 26 percent decline in regional public school enrollment by 2028.

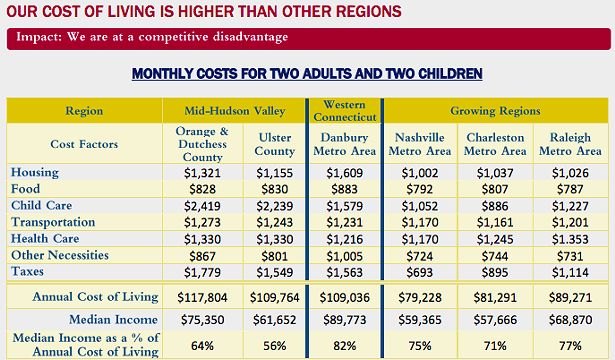

People are leaving the study area because of ballooning costs and shrinking wages—trends that also help explain why 48 percent of regional 18-to-34-year-olds are currently living with their parents. That percentage well exceeds state and national averages, indicating just how pricey it is to live here, according to Drapkin. Case in point, it’s significantly more expensive for a family of four to live in the Mid-Hudson Valley than in some mid-sized cities, including Nashville, Charleston, and Raleigh, according to a 2018 nationwide cost-of-living study by the Economic Policy Institute, cited in the Pattern for Progress report.

And it’s more than likely that Mid-Hudson Valley seniors are going to feel the pinch intensify in the coming decades. The 2015 AARP report also found that nearly a quarter of Dutchess County Gen X and boomer voters don’t have a workplace or personal retirement savings account. In fact, half of private industry-employed New York State residents lack an employer-sponsored retirement savings program, according to AARP’s New York State director, Beth Finkel. AARP successfully advocated for New York State's Secure Choice, a retirement savings plan that is voluntary for employers and that employees must opt into. Now, the organization is advocating at the state level that employers must offer an IRA savings option, if they don't already offer employees another way to save; employees would then have to opt out if they didn't want to participate. It’s worth noting that Americans whose employers provide a retirement plan are 15 times more likely to save for retirement.

On the other hand, Drapkin notes, there is “tremendous stress” on the regional workforce and not enough people to fill jobs. There are also plenty of older people who don’t want to retire just yet. “Maybe they're not as savvy at technology, but we can coax some of them back into the workforce.”

An Aging-in-Place System in Need of TLC

Any discussion of aging in the Mid-Hudson Valley and how to deal with it must also consider the region’s rapidly diversifying population. Between 2007 and 2010 in Dutchess County, for example, the Asian population increased by 35 percent, while the African American and Latinx populations went up by 67 and 62 percent, respectively, according to a forthcoming AARP report, “Disrupt Disparities 2.0,” publishing in late January. County offices for the aging and local governments “might not be set up to respond” to culturally specific needs, notes Finkel. The percentage of people of color moving into nursing homes is increasing nationwide, for example, despite most people vastly preferring to age in their own homes.

Expanding access to in-home care is not only “the right thing to do because people want to age in place,” says Finkel; it’s also fiscally responsible, costing less than nursing home care and supporting local economies. At least 72 percent of nursing home payments in New York State are covered by Medicaid, a major contributor to the state’s $6 billion budget deficit. And when people stay in their homes, they also continue paying property taxes and shopping at grocery and drug stores. As for seniors in remote areas who may want to age in place, Drapkin points to possibilities like telemedicine, which will require a “true solution to rural broadband” throughout the region.

In 2018, Governor Cuomo added aging, as well as disparities among communities of color as they age, to his health prevention agenda. The state has also begun investing $15 million in counties with waitlists for home-based care services, including long-term care services for Medicaid-ineligible families. But there’s a statewide shortage of home health aides, and family caregivers are filling the gap, putting an average of 20 percent of their annual earnings toward related expenses, from medications to meals to home modifications like wheelchair ramps and accessible showers. Cuomo has yet to approve a proposed Caregiver Tax Credit of $3,500 per year to help cover some of those out-of-pocket costs.

The Meaning of “Age-Friendly”

On the whole, New York State has been making strides toward accommodating an older population. New York became the nation’s first age-friendly state in 2017, a World Health Organization and AARP designation that recognizes high marks across eight age-friendly categories, such as transportation, community and health services, and housing. Earlier this year, Ulster and Orange counties were awarded funds from the New York State Age-Friendly Planning Grant Program. The money can go toward revitalization features like enhancing and creating open spaces, improving public transportation, and expanding affordable housing options in walkable downtowns—qualities desired by seniors and millennials alike.

“What's fascinating to me is that this is not just about older adults,” says Finkel. “An age-friendly community could be age-friendly for all ages.”

Over the past several weeks, Drapkin has been traversing the region to meet with groups of residents in all seven counties. His goal: to explain the results of the report, and suss out peoples’ greatest concerns. Pattern for Progress will publish a follow-up report detailing potential strategies and recommendations for the region, inspired by locals’ input as to how they want local and state leaders to tackle different issues.

When he broached the topic of aging, Drapkin discovered a lack of outside-the-box thinking. Most people still associate getting older with retirement and sickness, he says, but in reality, Americans are living longer, and many either don't want to or can't retire.

“There’s still a lot of work to be done in terms of imagining what to do with, nationally, millions of people,” he says.

But amid the report’s findings and his discussions around the region, Drapkin finds much to be inspired by. With the growing desire among older adults to stay in their homes as they age, for example, tech-savvy millennials could team up with local carpenters unions to retrofit houses while helping elderly folks get the hang of new home technologies like smart sensors and voice-activated personal assistants. Drapkin also envisions local colleges building on-campus senior housing, as SUNY Purchase has done. And he wonders about a multigenerational solution: zoning amendments to allow for houses owned by empty-nester boomers to be reconfigured into two-family homes, creating new affordable housing for millennials.

“With the size of the housing crisis we have now, we’re going to need dozens of solutions,” says Drapkin. “I look at this report as full of opportunities.”

This article was published in the February 2020 issue of Chronogram.