October 1947. What appears to be Brooklyn. An impossibly towheaded shoeshine boy named Mickey takes a break from his work and leans against a lamppost, eating a hot dog and having an animated conversation with his pal in the Huntz Hall hat. A chainlink-fenced industrial yard containing giant oil tanks—perhaps where Mickey and his friend's fathers work—looms behind them.

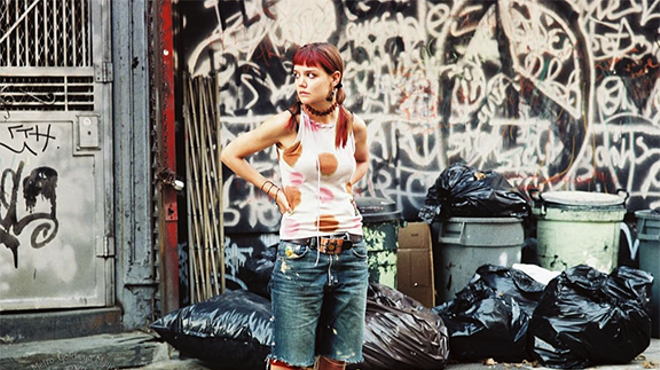

March 1948. An aspiring actress who's a dead ringer for Heddy Lamar, positioned and straining just so, to emphasize the claustrophobic confines of her walk-up's cramped kitchen, has her Hollywood moment. In another frame, the struggling starlet is backstage at her bill-paying gig as a scantily clad showgirl, applying makeup with defeated detachment.

The scenes are flawlessly composed and constructed, with fanatical attention to detail. Each looks like it's from a movie. Which makes perfect sense, when you consider that they were made by one of moviedom's most painstakingly "visual" and detail-obsessed filmmakers: Stanley Kubrick, during the days he worked as a staff photographer for Look magazine in the late 1940s, before he began his subsequent career. Kubrick's photos for Look are the focus of "Through a Different Lens," an exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, and a lavish, identically titled companion tome published by Taschen Books.

"These photo features were supposed to tell stories, and Kubrick stuck to the script, as it were, when he was creating them," says writer and historian Luc Sante, who penned "Learning to Look," an introductory essay for Through a Different Lens. "It's clear he wasn't intended to remain a photographer. But his photos from that time are important, because they show us a completely lost world."

Kubrick, of course, stands as a cinematic icon, the director of such monolithic, culture-shifting masterpieces as Paths of Glory (1957), Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), The Shining (1980), and Full Metal Jacket (1987). But few today are aware of his humble, workaday beginnings as a maker of still images. Born in the Bronx in 1928 to Eastern European Jewish immigrants, Kubrick began his initial, photographic phase when his father presented him with a high-end Graflex camera on his 13th birthday.

Look magazine in the 1940s was the perfect print outlet for this budding young lensman. Founded in 1937, it was the biweekly rival to the weekly Life, which, of the two, tended to feature more wholesome content and cover more international topics. Look had those elements as well, but its longer lag time between issues allowed its creators regular opportunities to embed themselves further while cultivating story matter, and much of it came from just outside their Manhattan offices. In 1945, bypassing college, Kubrick became a Look staffer at the astonishing age of 17 and remained at the magazine until 1950. "By the time I was 21," he said later, "I had four years of seeing how things worked in the world."

His photos for the publication cut straight to the seasoned souls of his subjects, uncannily conveying experiences well beyond most the teenager taking their picture would have known himself. Reprinted in Through a Different Lens are Kubrick's mass-market-satisfying pictorials of celebrities like bandleaders Guy Lombardo and Vaughn Monroe and doomed matinee idol Montgomery Clift. But equally impactful as the shots of famous figures—often more so—are the ones of "regular" people, on the sidewalks, in the subways, and in the bygone theaters and dancehalls of New York. Many of these tableaux were cleverly staged for Kubrick's camera.

A marked film-noir feel permeates much of his work here, and this aesthetic clearly found its way into two of his earliest films, the genre gems Killer's Kiss (1955) and The Killing (1956), as well as the suffocating settings of Dr. Strangelove (a July 1947 spread on the on-location shooting of Jules Dassin's noir classic The Naked City was certainly a formative assignment for the auteur-to-be). By 1951, though, Kubrick had seen what he'd needed to see at Look. He left the magazine and picked up a different kind of camera. That year, he made his directorial debut with Day of the Fight, a short boxing documentary no doubt informed by his Look pictorials on prizefighters Rocky Graziano and Walter Cartier. After that, he was on his way, launching his fabled feature film career with Fear and Desire in 1953 and finishing it with Eyes Wide Shut in 1999, the year he died.