Historical Reference

"All of the houses were newly built and had little driveways, but nobody had a car," says Luc Sante about suburban Verviers, Belgium, where he was born in 1954. "There was only one family with a TV set in the neighborhood. By 1963, though, the 'economic miracle' [postwar European growth] had happened, and everyone had cars and TVs." Despite the period's resurgence, however, there were still glimpses of a Europe that hadn't fully emerged from the 19th century. "My early classrooms featured potbellied stoves and double desks with inkwells, into which we dipped our nibs," Sante recalls in The Factory of Facts, his childhood memoir. Sante is the author of several books, most famously Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York, and reams of writings concerned with art, culture, and, especially, history. He traces his fascination with the latter subject to an early interest in the Romans who colonized his homeland in the fourth century, although it was the visual arts that initially sparked his vocational ambitions. "At first, I wanted to be a cartoonist," he says. "[wing-helmeted Franco-Belgian comic strip characters] Asterix and Obelix were around, and I loved them. But I'm colorblind. So that wasn't going to work."Although the economic miracle benefitted many Europeans, it didn't arrive soon enough to secure Sante's father's position as a foundry foreman. By the time the recovery was settling in, the Santes had settled in New Jersey. There, young Luc resumed his education while learning the language. "Wanting to be a writer came from the act of learning English," he says. "When I was 10, one of my teachers told me I'd be a good writer, although I didn't think much of it at the time." A family trip to Montreal for Expo 67 included a visit to a French-language bookstore where he discovered Rimbaud and the Surrealists, and by age 13 he was devouring everything from the Bronte sisters and Thomas Hardy to Naked Lunch and Henry Felsen's teen hot rod novels. He also started pitching articles. "I'd buy Writer's Digest and respond to the listings," he says, with a dry smirk. "I submitted all this filler—to boating magazines, whoever was looking for writers—but nothing ever got published."

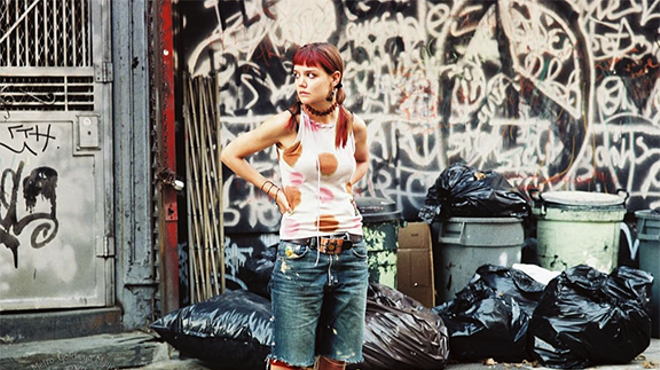

The pull of poetry and the counterculture led Sante, naturally, to the Lower East Side. By 1968, he'd become a St. Mark's Place habitué, going to concerts at the Fillmore, haunting the record racks at Free Being, and buying egg creams from Gem Spa and $10 bags of pot from surreptitious slots in 10th Street storefronts. A scholarship got him into the exclusive Regis High School on the Upper East Side, and studies under the Pulitzer-winning poet Kenneth Koch at Columbia University came next. But it soon became clear that poetry was not to be his calling. "I could never get into the rhythm [of poetry]," he says. "Line breaks bothered the shit out of me, and you can't be a poet without line breaks." His disinterest resulted in his leaving Columbia in 1976 without a degree. Around this time, though, came other awakenings.

"For the last two years at Columbia, I'd been living in crumbling building on 118th Street," Sante says. "Then I moved into an apartment on the Upper West Side and, eventually, a tenement in the Lower East Side. You'd scrape the paint on the window sills in these places and there'd be layer upon layer of it. I discovered that one of the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire had lived in my building on 12th Street, and that Mozart's librettist, Lorenzo Da Ponte, had been buried on my block. These buildings were like palimpsests. They made me wonder about the lives of all the people who had lived in them over the years."

One of Sante's roommates was a fellow Columbia/Koch student Jim Jarmusch, then a writer and musician, and, like Sante, a denizen of the embryonic punk scene exploding in and around CBGB. The two hosted public readings of their work, and Jarmusch formed a band, the Del-Byzanteens, for which Sante occasionally wrote lyrics. In 1980, he got a job in the mailroom of the New York Review of Books and eventually became editor Barbara Epstein's assistant and a long-serving staff writer at the magazine. While researching a freelance story, he came across some revelatory nuggets of hidden New York history that included a startling first-person account of the 1863 Draft Riots. The discoveries reinforced his obsession with the city's lost voices. "Herbert Asbury's The Gangs of New York had been passed around a lot when I was at Columbia, and I'd loved that book," says Sante. "I decided I should write a history of the slums."