The Schoharie County Democratic Party’s annual late summer BBQ is the typical launching pad for its campaign to court the local electorate’s vote. In a typical year, dozens of party faithful gather to break bread, listen to speeches, pick up yard signs, and socialize in the final weeks of yet another election cycle.

But much like everything else in 2020, the coronavirus disrupted this time-honored tradition. Sure, the party faithful in Schoharie County still convened in mid-September, but only to drive through an assembly line of masked volunteers handing out barbecued chickens and yard signs. A hootenanny it was not.

The spread of COVID-19 across the United States has severely altered almost every aspect of everyday life, from supply shortages of vinegar to in-person education. Elections aren’t spared. When it comes to campaigning during the pandemic, the modern political playbook has been completely tossed out the window.

Or, as Greene County Democratic Party Chairwoman Carolyn Riggs explained to The River a few weeks ago: “Door knocking, one-on-one in-person conversations, and meet and greets are kind of a part of that playbook. And those things have been stripped away.”

In an era of social distancing, facemask mandates, and half-capacity regulations for indoor meetings, what exactly does this all mean for political campaigns heading into the homestretch of the 2020 election cycle?

A Changed Playing Field

New York State Assemblyman Chris Tague (R-102) is a hardened veteran of Republican campaigns; he first volunteered for his father’s run for a council position when he was just four years old. Politics is “something that came natural, being born into it,” Tague says, but he sees this campaign changing everything.

Tague thrives on traditional retail politics like door-to-door campaigning and going to events. To put it mildly, “that’s going to be a struggle, because a lot of people are scared,” Tague says. Tague hopes to instead reach voters with safer, if less personable, alternatives, such as “lit drops” and direct mailers.

For Tague, there have been personal reminders of the dangers posed by the virus: The lawmaker notes that two of his close friends have contracted COVID-19 and nearly died as a result, including retiring New York State Senator James Seward (R-51).

“There are no Democrats who are door knocking. It’s kind of a top-down message,” says first-time candidate Betsy Kraat, who is Tague’s Democrat opponent in the 102nd district. Noting that “no one wants to be that person” who causes a contact-tracing panic, Kraat says her campaign has begun wearing “Betsy for Assembly” T-shirts at local events to advertise their presence without walking up to people.

Whereas politicians used to balance the risk-reward of someone shutting a door in their face or unleashing their dog upon them while campaigning, the risk of contracting COVID-19 has raised the stakes for not properly following safety procedures.

This is something that Leslie Berliant, cofounder of the Democratic Party-aligned Rural Majority Project, understands all too well. As campaign manager for Jim Barber’s state senate campaign in the 51st district, Berliant had to face a political consultant’s worst nightmare in 2020.

One day before Barber was set to visit the Pakatakan Farmers Market on July 4, which was supposed to kickstart the candidate’s return to in-person campaigning after months of virtual events, Barber learned that he might have been exposed to the coronavirus.

The campaign canceled everything that weekend until they got a test back. Berliant described the waiting game as “very nerve-wracking,” but Barber’s COVID-19 test came back negative a few days later, to much relief. Barber rescheduled, eventually visiting Pakatakan in late August.

Despite the campaign’s inauspicious return to in-person politicking, Berliant says that “people were extremely supportive and very, very grateful for our caution.” The campaign’s Facebook post announcing Barber’s negative result is among the most liked of the Fulton farmer’s run.

Despite their political differences—and despite how national politicians have acted—there is little daylight between Berliant, Kraat, or Tague on the need to approach COVID-19 cautiously.

Zoom Out the Vote?

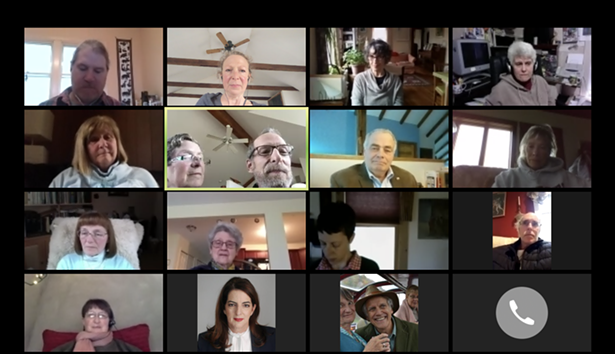

Some campaigns have tried to connect with voters by turning to Zoom and other virtual means.

Berliant’s years as a political activist in California, when she would have forty people at her house making phone calls to voters, have emphasized for her the word “social in social movements,” as volunteers gravitate towards coming together for a cause they believe in. Generating that same staff enthusiasm in that way is simply is not possible now.

Berliant says that campaigns are trying to “mimic what would happen in an office on Zoom” with phone-banking operations and fundraising events. But after months of virtual-only campaigning, “a lot of people are Zoomed out.”

This has led to a limited increase in in-person campaigning. Barber’s campaign recently cohosted a socially distant outdoor campaign rally in Auburn, but the campaign has remained largely focused on remote activism that involves volunteers making phone calls or writing postcards from home.

Neither Tague nor Riggs could ballpark the eventual effectiveness of virtual events held on Zoom or other platforms. “When you’re talking to voters in a digital platform,” Riggs says, “most likely those are different voters than if you were knocking on doors or attending the county fair.”

Voters that campaigns reach on digital platforms are a “different subset,” she adds, more likely to be politically motivated than your average constituent.

“It’s just not the same as going to the kite festival in Cherry Valley,” Berliant says.

With the traditional get-out-the-vote approaches unworkable and the efficacy of the Zoom-out-the-vote approach untested, Tague believes that safer alternatives such as lit drops—where campaign volunteers drop off materials promoting a candidate or ticket on a targeted voter’s doorstep—and direct mailers are going to be more prevalent.

But those methods aren’t without flaws, either. Mailers are a double-edged sword, Tague says, because voters “may throw it in the garbage.” And reaching voters via direct mail will be more expensive this election cycle because turnout is typically higher in presidential years than off-cycle years, which means more voters to reach.

“I think it’s probably going to cost my campaign more money this election cycle than it even did when I ran a special election and a general election [in 2018],” Tague says.

All Votes Lead to Election Day

Although almost every aspect of modern political campaigning has been upended by COVID-19 this year, one truism will remain the same with just a slight caveat: whoever wins the most votes by election day will win the election.

Turning out the vote on Election Day is the end game of every political campaign, but this year offers an additional twist: no-excuse absentee ballots and early voting, which are not only safer alternatives to in-person voting during a pandemic, but might result in more votes being cast before November 3 than ever before.

- How to Make Sure Your Vote Counts This Election Day: The River’s 2020 voting guide

Voters and campaigns in New York’s 19th Congressional district already have some experience with this relatively new phenomenon, when an unprecedented amount of Republican primary voters took advantage of absentee ballots in June’s contest between eventual nominee Kyle Van De Water and his rival Ola Hawatmeh.

While Hawatmeh led by several hundred votes on election night, Van De Water ended up winning by several thousand votes after absentees were counted. This led to unfounded allegations of fraud by Hawatmeh, and it is a preview of what might happen this fall if elections are too close to call on November 3, with absentees outstanding.

Tague predicts there will be “a lot of races on election night that we’re not going to know who the winner is,” citing not only the 19th Congressional district, but a slew of close June Democratic primaries in New York City that weren’t resolved for nearly six weeks.

Regardless of party affiliation, all four interviewees for this article support early voting and no-excuse absentee ballots, and believed that November’s turnout could be quite impressive. Berliant and Riggs are pushing early in-person voting, in particular, because it avoids the voter error and delivery challenges that absentee ballots can face.

Whether votes are cast by absentee ballot, early, or on Election Day itself, Riggs is adamant that any voter who might be thinking of sitting out this election should remember “that it is a privilege as an American to vote.”