If you listen to the CEOs of the largest firms, you might conclude that after the pandemic, the overwhelming majority of knowledge workers would be returning to the office. But mounting evidence says that’s not so. This will have major impacts, not only on the central business districts of New York City and other “super cities” like San Francisco and Chicago, but also on the peripheral suburban and exurban regions surrounding them.

Researchers like Adam Ozimek and economists Arjun Ramani and Nicholas Bloom have begun to quantify the scale of this shift toward remote work, and the migration away from the ‘superstar cities’ like New York, San Francisco, and some others. Today, one recent survey estimates, 14 to 23 million Americans are planning to move as a result of remote work becoming mainstream. In the Hudson Valley, this could mean hundreds of thousands of relocations.

The implications for the Hudson Valley are stark. We can expect an acceleration and broadening of problematic trends we’ve witnessed in the past few years, including inadequate affordable housing, lack of skilled work in the regional jobs market, and pandemic-linked pressures on schools and childcare.

The Rise of Remote Work

The pandemic forced companies to accommodate working from home, and accelerated the adoption of technologies that made that possible, such as video meeting tools and chat applications.

In March 2020, though, the prevailing opinion—especially of management—was that the workplace would revert to the status quo ante after the decline of COVID-19 infections. It’s clear that many business leaders like being in the office, and they make various arguments in favor of returning, including:

- Serendipity at the water cooler can't be emulated remotely

- “Management by wandering around” is difficult with remote workers

- Culture-building is hard or impossible to accomplish remotely

- Workers, especially younger and newer hires, need to learn by working alongside experienced workers

- In-office work leads to higher employee engagement

But the ability to work remotely is a high priority for a large and growing chunk of the knowledge workforce, especially for women, people of color, and working parents, Future Forum found in a recent survey.

What’s more, remote work was yielding higher engagement and productivity prior to the pandemic. A Gallup report titled “State of the American Workplace” from 2017 showed a paradoxical finding: Employees who spent at least some (but not all) of their time working remotely have higher engagement than those who never work remotely. Those who work remotely the majority of the time are more likely to strongly agree that doing so makes them more productive.

So the rationale for having employees come to the office 9 to 5, five days a week, was already wearing thin. However, corporate inertia and belief in the supposed benefits of serendipity and group interactions led business leaders to stick to their old ways.

And then, the pandemic proved it was possible for most knowledge work to be done remotely. Now, people say they like remote work, and resist returning to the office. The Pew Research Center reports that among workers who have access to the office but are continuing to work remotely, 76 percent cite a preference for working from home, up from 60 percent in 2020.

There are many benefits for the individual working from home:

- The reduction or elimination of time commuting, and commuting related-expenses, like expensive lunches

- Reduced time and expenses dedicated to clothes and grooming;

- Less office politics and group dynamics, like the need for “performative work,” such as getting into the office before the boss

- Greater personal autonomy—clearly a factor in reported productivity improvements

- Better work/life balance, since time formerly dedicated to commuting, grooming, and so on can be allocated to exercise, family, or outside interests

- More time with family

Childcare was and is a major factor, falling most heavily on women. As Pew’s research shows, 32 percent of teleworking parents whose workplaces are open say childcare is a major reason why they are working from home all or most of the time, down from 45 percent in October 2020.

While most of the outcomes of remote work seem positive, there are some downsides:

- Some at-home workers experience loneliness, especially those living alone;

- There is a fear of missing out on what is going on in the office and being left out of social groups;

- There is a well-documented proximity bias among business leaders, where those in direct contact with bosses are more likely to be selected for new initiatives and assignments, perhaps leading to promotions;

- Some companies responded to work-from-home with computer-based surveillance of workers, either indirectly (such as analyzing workers’ time logged into company applications) or directly via apps installed to monitor workers. This has led to anxiety for many.

The reality is that most businesses have already adopted a hybrid model of work, where work is distributed across different contexts at different times. Instead of a competition between headquarters and home, we might instead think of the new workplace as a network of spaces connected by technology, as described by the urban ecologist Richard Florida: “An interconnected ecosystem [that] could span not just a central office location but also the home offices, co-working spaces, coffee shops and other third spaces that support remote work in the suburbs or outlying areas.”

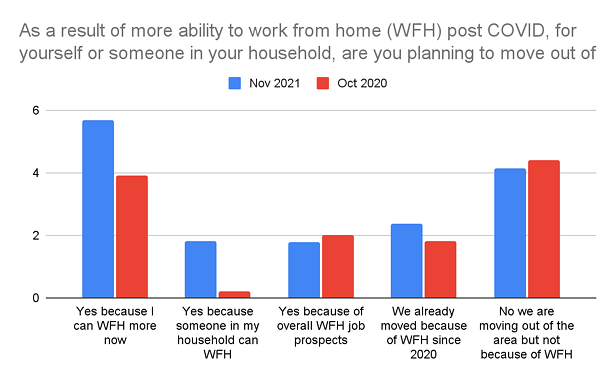

Perhaps the most critical aspect of the rise of remote work with regard to the Hudson Valley is this: as a result of the pandemic, many former residents of large urban settings—like New York City—and their surrounding suburbs have relocated. The Pew report found a significant increase since 2020 (from 9 percent to 17 percent) in the number of teleworkers who have relocated away from the area where they work.

This coronavirus-driven relocation from major US cities, and especially from New York City, has had and will continue to have major consequences for the Hudson Valley. To understand that, we need to understand what is going on.

The Donut Effect

Economists Arjun Ramani and Nicholas Bloom have done groundbreaking research on the migration of Americans due to the rise of remote work, reported in “The Donut Effect of Covid-19 on Cities.” Using data from the postal service and Zillow, they discovered a hollowing out of dense central business districts caused by people moving to lower-density suburban and exurban areas. They write:

While this observed reallocation occurs within cities, we do not see major reallocation across cities. That is, there is less evidence for large-scale movement of activity from large US cities to smaller regional cities or towns. We rationalize these findings by noting that working patterns post-pandemic will frequently be hybrid, with workers commuting to their business premises typically three days per week. This level of commuting is less than pre-pandemic, making suburbs relatively more popular, but too frequent to allow employees to leave the cities containing their employer.

Ramani and Bloom

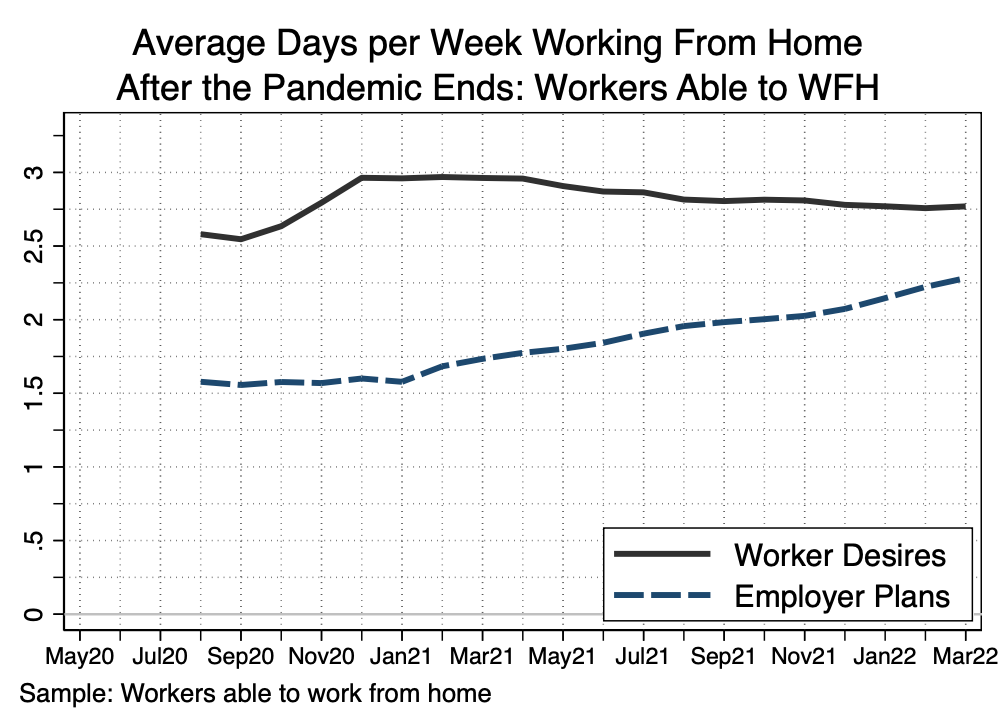

Bloom and other researchers track several key indicators of this migration, including the claim that employers will plan on a hybrid mode of work. In an April update based on recent survey data, they reported that employers’ plans are now trending toward three days a week of work outside the office for workers able to do their jobs from home.

Adam Ozimek of Upwork confirmed the findings of Ramani and Bloom in a survey of over 23,000 people. He estimates that “anywhere from 14 to 23 million Americans are planning to move as a result of remote work. Combined with those who are moving regardless of remote work, near-term migration rates may be three to four times what they normally are.”

Ramani and Bloom determined that a small number of “superstar cities” were the central loci of these donut effects, such as New York City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and nine others. Of those who considered moving, 28 percent planned to move more than four hours away. That’s well beyond typical commuting distance.

In the New York Post, Nicole Gelinas recently reported that prior to COVID, 1.1 million people from Connecticut, New Jersey, and elsewhere in New York came into Manhattan to work at a desk each day. Now, only 28.6 percent are back, most not every day.

If 45 percent of those 1.1 million commuters move to the periphery of the donut, we could see a few hundred thousand people moving into the Hudson Valley, suburban New Jersey, Connecticut, and perhaps as far as Cape Cod.

In an April article for The New York Times, Dana Rubinstein and Nicole Hong summarize what’s happening in New York City, naming marquee companies with city headquarters who have adopted remote working, like PwC (40,000 US employees who can work remotely forever), Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan (its staff can live anywhere in the country), and Verizon (permits hybrid employees to come to the office as many, or as few, days a week as they want).

And the impact on the city’s finances? “With more companies settling into a permanent period of hybrid work, the average New York City office worker is predicted to reduce annual spending near the office by $6,730 from a pre-pandemic total of around $13,700, the largest drop of any major city,” Rubinstein and Hong write.

Remote Work in the Hudson Valley

The Donut Effect is having a large impact in the Hudson Valley, as those formerly commuting to New York City on a daily basis now expect that they will not need to do so because of the widespread acceptance of remote work. So they are migrating farther out, to the edge of the Donut.

From Ozimek’s Upwork report, “The New Geography of Remote Work” (emphasis mine):

If we zoom out of the New York City house price growth map above, we can see that the donut around New York City is far larger than the immediate suburbs within the metro area. Large swathes of Pennsylvania and New Jersey appear to be in the donut area for New York City. These areas include places like the Poconos, Allentown, and south Jersey that are outside of the metro area and the state. Some areas in the donut are sparse rural areas that are more than two hours drive from New York City. What’s more, these farther away areas are seeing more rapid price growth than the closer suburban donut immediately surrounding New York City. In short, if this is the donut effect, it does not rule out fairly long-distance moves to rural, low cost places well beyond the New York City suburbs.

Though people are moving to the periphery of large metro areas, there is little corresponding evidence of economic activity being equally spread out. As Ramami and Bloom show, within a metro area the densest neighborhoods have declined—like Manhattan and Brooklyn—but the densest greater metropolitan areas have not. We will still see high rental and housing prices in the densest areas, even as fewer people commute in from the suburbs and exurbs.

And these effects are still in process. As Ozimek writes, “it is important not to assume that the moves we have seen to date represent the long run effects, there are strong reasons to suspect longer-term moves will grow.

Regional Issues for the Hudson Valley

The geographical impacts of remote work on the Hudson Valley will be deep and broad. Perhaps most critically, the in-migration of knowledge workers from New York City will accelerate the regional housing crisis.

As I wrote for The River last October, there are really two different housing crises: a lack of affordable housing for low- and moderate-income residents, and a skyrocketing marketplace for single-family homes among high-income residents.

At the same time, I quoted Wally Adeyemo, the deputy secretary for the treasury, who pointed out in June 2021 that “no state in the country has an adequate supply of affordable housing for the lowest-income renters.” Nothing much has changed. US housing construction slowed from 1 percent between 2000 and 2010 to 0.7 percent the following decade. To meet actual demand over this decade, housing would have to grow to at least two million units a year, an increase of 60 percent over 2020’s pace. That is simply not going to happen.

We can anticipate, then, that the ills associated with the shortage of affordable housing will get worse, and quickly. These include more homelessness, more families spending too much of their income on housing, increased commuting as people are displaced by rent increases, and many secondary effects, like food insecurity.

As housing values rise, the most attractive municipalities may be able to accrue higher property taxes, which could underwrite social programs to offset the worst impacts of a surge in population, but it is unclear if such programs are being contemplated. New York Governor Kathy Hochul seems more inclined to exhorting knowledge workers to return to downtown New York City offices, rather than seeking to respond to what is happening.

Dutchess County recently released a Housing Needs Assessment that stands as a proxy for the region’s problems in general (emphasis mine):

The HNA report reviews historical data and trends, which demonstrate that housing affordability challenges are not new in Dutchess County, however long-term shifts in demographic, housing, and economic trends create new urgency for action, as more households than ever are experiencing trouble affording housing. While the COVID pandemic amplified housing challenges, the analysis shows many of these trends were well established by 2019.

Among the long-simmering trends contributing to the current housing situation:

-Population growth has leveled off while the median age in Dutchess County continues to rise. As many older residents choose to “age-in-place,” the number of homes available for younger families looking to buy into the housing market tightens

-Average household size continues to decline, leading to growth in total households even as overall population growth levels off

-Income growth has lagged behind housing costs, particularly for many renters and lower-income households, resulting in more cost-burdened households

-Growth in the number of higher-income households has exerted unexpected pressure lower down in the housing market

-The assessment includes a gap analysis, the difference between the number of units in a given price range and the number of households for whom the price range is affordable. Of note, Dutchess County currently lacks housing units for both the lowest and highest incomes. The limited availability of housing on the high end is a new challenge—as households with more purchasing power compete for a limited supply of units, they begin to reach down into the middle sectors of the market, creating a ripple effect through the entire market and affecting housing affordability at all levels.

Dutchess County’s plan uses a 20-year timeframe to create 2,155 additional affordable housing units. That comes out to 108 new units per year—an inadequate response, especially since the donut effect is likely to continue for years. And of course, this is only one county, attempting to confront a regional crisis without a regional response.

Here are a few additional impacts of the donut effect:

- Regional work. We can anticipate service job growth across the Hudson Valley, as knowledge workers move to the periphery and commute less, and take advantage of local services. If we want sustainable, well-paying jobs, we will need more than retail and distribution jobs. Can we transition to creating more knowledge workers locally, instead of just an in-migration? We can expect the demand for construction-related work to continue, and that more distribution centers—such as Amazon’s—will move to the periphery.

- Reuse of industrial buildings: We can expect more demand for commercial buildings, as more knowledge workers move to the area, start small businesses, open coworking spaces, and increase demand for stores and restaurants.

- Transportation: Less commuting is good for the environment, but many will still be commuting into New York City, just less frequently. This could decrease revenues for the MTA and city transportation services, and increase the need for regional transport. Fewer cars on highways, but more on local roads.

- Childcare and schools: Demand for childcare and increased school enrollment is likely as younger knowledge workers move to the region and start families.

- Infrastructure: Many Hudson Valley municipalities are struggling with infrastructure issues, such as sewage treatment, sewers and water supply, roads and bridges, and gas and electricity. While higher tax revenues may help, it is likely that such issues will continue to pose serious challenges.

What is needed, above all else, is a regional response to the challenges posed by the remote work transition and the impacts of the donut effect. As of yet, there doesn’t seem to be enough planning to counter the new stresses the Hudson Valley faces.