We first encounter Amanda Palmer at a local bar. She's scrunched up quietly in a corner. Loud music and revelry swirl around her stool, where she's intently perched, facing the wall—pen in her hand, draft beer at her side. If anyone else in here recognizes the celebrated solo artist and front woman of the Dresden Dolls, they're letting her be. And that's fine. She's not here to sign autographs, or to party. Instead, the manuscript of her new book, The Art of Asking (Grand Central Publishing), designed to "inspire readers to rethink their own ideas about asking, giving, art, and love," lies spread open before her. Palmer, engrossed in its pages, is here to edit the thing. For a music editor used to the tomb-like solitude of his hermetically sealed garret, the thought of attempting to work within the eye of such a Koyaanisqatsi-esque hurricane brings vertigo and nausea.

"Oh, I've always written in bars and cafès," Palmer says casually a few weeks later. "I work well around the energy of people."

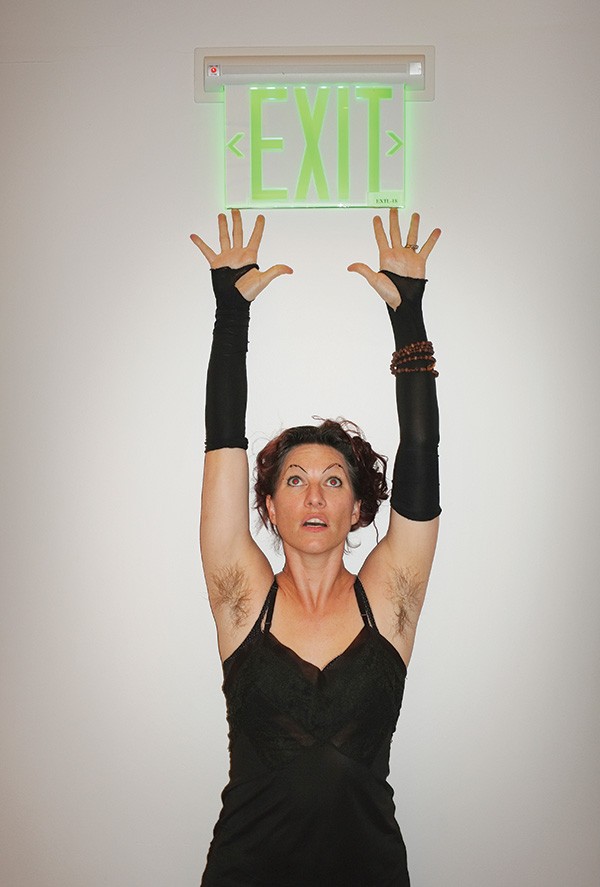

Whatever environments Palmer chooses in which to create her art, which includes not only includes her music and other books but also numerous theatrical productions and performance art projects, they've clearly been conducive. One of today's most thought-provoking indie icons, Palmer regularly headlines theater-scale venues around the world and is the recipient of racks of awards. Her fervent fan base can't get enough of the singer-songwriter's provocative aesthetic and edgy brand of punk cabaret, a phenomenon borne out by the 2012 Kickstarter campaign for her sophomore album Theatre Is Evil (8ft. Records), which netted nearly $1.2 million—the most money ever generated for a single music-album project via the popular crowd-funding website.

But perhaps Palmer's greatest art is how she's helping redefine the concept of how to truly be an independent musician. Instead of relying on the rapidly eroding traditional music industry or futilely fighting file sharing, she's encouraging fans to take her music for free online—with the proviso that they contribute what they can out of goodwill. For Palmer it's merely a grand-scale evolution from her beginnings as a street performer and the DIY world in which she's long operated. "The media asked, 'Amanda, the music business is tanking and you encourage piracy! How do you get all these people to pay for music,?" she says in a video of her talk at a 2013 TED Conference. "The real answer is: "I didn't make them, I asked them.' Through the very act of asking, I connected with people. And when you connect with them, people want to help you."

Palmer grew up in the Birthplace of American Liberty: the Boston suburb of Lexington, Massachusetts. "I knew I'd be a performer when I was still in the womb," she jokes. "I've just always loved performing, and music." Both of her parents are lovers of the stage who took her to local musicals and encouraged her to take part in community theater. But she credits her mother with nurturing her musical obsession. "I remember being five or six and wearing headphones, listening to my mom's records," says Palmer. "The Beach Boys, the Doors, and especially the Beatles—I was always more Beatles than Stones." Piano, which she learned to play by ear, arrived earlier. "We had [a piano] in the house," the keyboardist recalls. "It was this magic machine, you pushed the buttons and music came out." The real magic, however, came in high school, where she joined the drama department and met her mentor, the teacher Steven Bogart.

"Before that I'd only ever done 'safe' community theater, and Steven was uninterested in that stuff," Palmer explains. "In his class, we were given permission to really explore and create. He only wanted to do real work, not bullshit. There were no productions of 'Our Town.'" Palmer later enrolled at Connecticut's Wesleyan University, where she felt alienated by the college's traditional theater program and "did my own thing, some one-woman shows." After graduating in 1998, she started the Shadowbox Collective, an experimental theater troupe that appeared at Boston's alternative venues, and began performing as the Eight Foot Bride, a miming character in white pancake makeup and a wedding dress who stood atop a milk crate in Cambridge Square handing out daisies and longing looks to donating passersby. The Bride had a five-year run and was a pivotal role, in more ways than one, for the developing musician-actor. "People would yell at me from their passing cars, 'Get a job!' and I'd be, like, 'This is my job,'" she recounts. "It made me fear that I was somehow doing something 'unjoblike,' shameful. I had no idea how perfect an education I was getting for the music industry [while standing] on top of this box."