This story first appeared in New York Focus, an investigative news site on state and city politics. It has been edited slightly here.

In June 2019, following a wave of progressive election victories and a months-long campaign by housing rights organizers, New York State passed its biggest expansion of tenant protections in decades. The Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act closed key loopholes in New York’s rent stabilization laws and extended them across the state, allowing cities to gradually opt in.

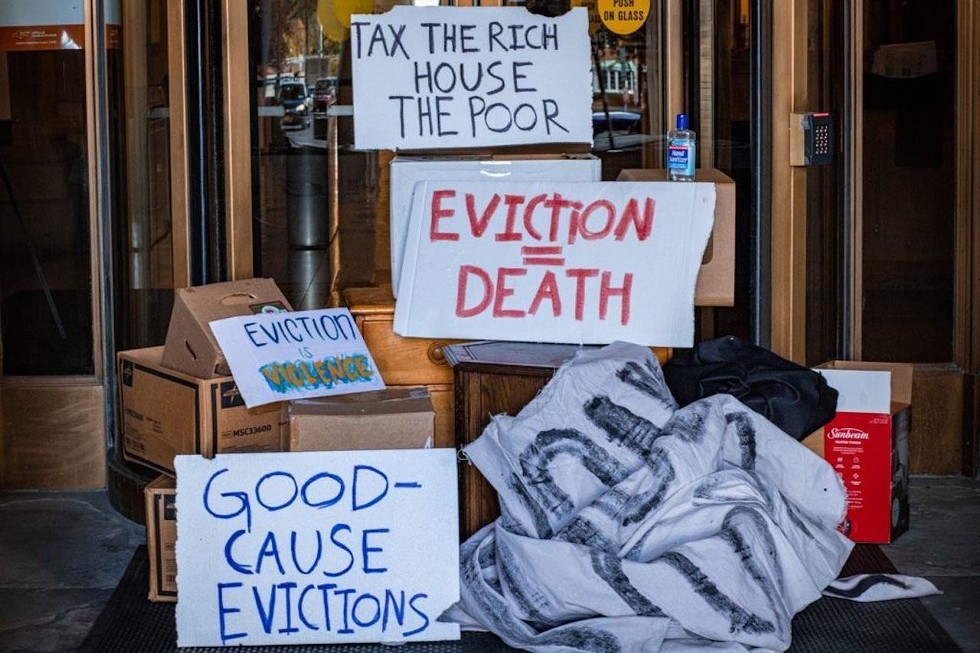

But for organizers, the 2019 law was missing a key component: “good cause eviction,” which would bar landlords from removing a tenant without justification. Two years later, despite a concerted campaign from organizers and progressive lawmakers, the policy is no closer to passing; the bill languished in committee in both the 2020 and 2021 sessions.

So organizers have shifted their efforts to the local level, backing a wave of new good cause bills in cities spanning from Albany to the Hudson Valley to Rochester and Buffalo. The first of those bills came to a vote in Albany on Monday, when nine of the 15 members of the city’s Common Council voted to approve the policy (four voted “present,” one was absent, and one voted against). Advocates hope it will not only protect tenants in the short term, but also help bring good cause out of its rut at the state level.

“It’s really important for the state legislature to pay attention and realize that the mandate is not just coming from the tenant movement, but from local government bodies that are clearly indicating that these are protections that are needed for residents across New York State,” says Rebecca Garrard, Albany-based legislative director at the advocacy group Citizen Action of New York.

Defining ‘good cause eviction’

Good cause, also known as the “right to renew,” would bar most landlords from evicting tenants unless they can show a “good cause,” such as failure to pay rent or violation of other terms of the lease. It would require landlords to offer a renewal lease to tenants in good standing and prevent major, arbitrary rent hikes, which advocates say are often used to push tenants out.

Opponents say the policy would place an excessive burden on small landlords, and is unnecessary given that New York already has some of the strongest tenant protections in the country. But organizers say the policy is designed precisely to protect the broad swath of tenants not covered by rent stabilization laws, which for now still apply almost exclusively to the New York City area.

“There is a massive housing crisis especially here in upstate New York, where there’s less regulation around rents and eviction,” says Brahvan Ranga, political coordinator at the grassroots advocacy group Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson. “The state legislature failed to address this crisis. [So] activists and local leaders are taking matters into their own hands, to start to pave the way for the rest of the state.”

Statewide, roughly half of tenants are rent-burdened, meaning they spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent, according to a 2019 report from the state comptroller’s office. One in four Black families and nearly one in three Latino families spend more than half of their income on rent. And nothing prevents landlords from raising rents further when a lease expires—in many cases, leaving tenants with little choice but to leave.

Proponents hope that implementing the laws locally will swing reluctant state legislators who say their constituents don’t want policies like good cause, and convince skeptics that the policy isn’t as radical as opponents make it out to be.

“This is just common-sense legislation that allows for tenants to understand what their rights are and to have clear rules of the road for our tenants and our landlords,” says Albany Mayor Kathy Sheehan.

Albany: ‘Politicians are listening to the people’

Monday “was a historic day, not just for the city of Albany, but for the state of New York,” says Garrard.

But Laura Burns, CEO of the Albany-area Greater Capital Association of Realtors (GCAR), says that the legislation demonstrated an insensitivity to local landlords.

“In the city of Albany, there are basically mom-and-pop operations. It’s not a conglomerate that owns it. These people are hurting right now,” she says. “At this time, when landlords are in the worst possible financial situation that they’ve been in for years, you’re going to take this action?”

Burns stresses that New York already has some of the strongest tenant protections in the country, and that the state should focus on enforcing those rather than adding new ones. But tenant organizers say existing laws, including the 2019 package, don’t protect tenants across most of the state from arbitrary evictions and rent hikes. The United Tenants Association of Albany says landlords filed 4,120 proceedings for eviction in the city court in 2019 alone. Moreover, organizers say the threat of eviction discourages tenants from demanding repairs even when conditions in their units reach unsafe or unsanitary levels.

Hasson Harris Wilcher, a 25-year-old Albany resident, describes growing up in these conditions. Raised by a single mother who worked as a teaching assistant, he found himself “bouncing around from place to place” before moving in high school to a building in the city’s historically Black South End.

“My bedroom was the addition that they added to make a second bedroom, and it continuously flooded, year after year, when it rained,” he says. “There were bubbles that formed and cracks that formed going right on top of my bed and down the side of the walls, so my bed was routinely flooded. It’s not something you can go ahead and talk about and tell people: ‘Oh yeah, I slept on a waterlogged bed.’”

Harris Wilcher, who has a degree in biomedical engineering and has worked as a teacher and medical technician since returning to Albany after college, says he felt recognized when the city council passed the good cause bill. “Politicians are listening to the people.”

Mayor Sheehan says the good cause bill, along with two other bills in a fair housing package, was the culmination of a “very long and deliberative process” dating back nearly to the beginning of her mayoralty in 2014. The pandemic put Sheehan’s housing reforms “on pause,” but as conditions returned closer to normal this spring, she and supportive council members bumped them back to the top of their agenda.

The recent focus on good cause in particular, she says, came largely at the urging of housing organizers. She attributes its passage to the fact that “the advocates showed up.”

“Albany used to have this reputation as a political machine,” Sheehan says. “If the mayor was in favor of something, it got done. I don’t run a machine…. I think it’s important for advocates to recognize that they’ve got to go and talk to every single council member and help to whip those votes. And the advocates in this case did that.”

Hudson Valley: ‘There’s absolutely no place to live’

Albany was the first stop in a campaign that housing rights organizers are mounting in cities across upstate New York. Organizers are picking cities based on local housing conditions—but also with an eye to persuading legislators seen as roadblocks to statewide good cause legislation that their constituents support the policy.

In cities like Albany, lawmakers note that one of the main aims of the larger fair housing package is to combat blight, as landlords often allow properties in low-income neighborhoods to fall into disrepair and, eventually, go vacant.

In much of the Hudson Valley, tenants are facing the flip side of that equation: rapid gentrification, fueled in part by New York City residents fleeing north.

“Housing prices here in Columbia and Greene counties have just gone through the roof,” says Michael Gattine-Suarez, Hudson-based managing director of the Hudson-Catskill Housing Coalition.

From 2019 to 2020, the city of Hudson saw the greatest spike in in-migration of any metro area in the country, according to a recent New York Times survey. Kingston ranks second. And prices are continuing to climb: a recent report by Pattern for Progress, a Newburgh-based research group, found that median home prices increased by an average of 23 percent across the Hudson Valley from early 2020 to early 2021, with no sign of letting up.

In Greene County, just across the river from Hudson, the most recent data published by the New York State Association of Realtors shows a more than 70 percent increase in median home values from the same time last year.

“With that comes speculative investors, who are just buying homes here in the Hudson Valley…to make a quick buck,” Gattine-Suarez says. He notes some landlords have sought to raise rents by as much as double when leases expire, and that without any kind of rent stabilization system in place, “there are no checks and balances.”

Gattine-Suarez has felt the consequences first hand. Originally from Brooklyn, he moved with his family to Poughkeepsie, then Kingston, and finally Hudson two years ago as rising rents chased him from one city to the next.

“Literally since birth, I’ve experienced this,” he says. He’s working with local lawmakers to craft a bill that would mirror the fair housing package in Albany, and hopes it could pass as soon as September.

Tiffany Garriga, Democratic majority leader on Hudson’s city council, says the bill would prevent tenants from being “bullied out of their homes for any kind of reason” and help combat the city’s accelerating housing crisis.

“People are getting priced out, bought out, and the outcome is that there’s no option. There’s nothing affordable,” Garriga says. “We’re hitting a mark in the city where there’s absolutely no place to live.”

Garriga says some of her fellow council members are “a little skeptical” of good cause, “but once they get a full understanding of the law, I think they will understand and see that it works for both sides.”

Ranga, of Nobody Leaves Mid-Hudson, says it’s urgent that municipalities pass good cause as quickly as possible, to prevent vast numbers of people being pushed out of their homes after New York’s statewide, COVID-19 eviction moratorium expires on August 31.

“There is a looming eviction catastrophe that is going to happen at the end of next month once the eviction moratorium expires,” Ranga says. “Skyrocketing” rents across the Hudson Valley have only added to the pressure, with many tenants facing significant rent arrears.

Ranga and other advocates hope New Paltz will be next in line to pass good cause legislation after Albany. Alexandria Wojcik, deputy mayor of the Village of New Paltz, introduced a draft good cause bill earlier this month.

“People are being de facto evicted and booted from the community…just because there aren’t these really necessary protections that, I think, have an emphasis on fostering communication,” Wojcik says. She hopes her bill will come up for a vote in late August or early September, after a public comment period.

Ranga says organizers also have their sights on Beacon, Kingston, Poughkeepsie, and Newburgh, though campaigns in those cities have yet to get underway. “We’re hoping the Village of New Paltz and the Albany campaigns are the first in a line of many municipalities across the area to enact this legislation.”

‘A starting place’

Ultimately, many organizers sees local efforts as setting a bar for equitable housing across the state—and paving the way for tenant wins in the state legislature.

“The reality is we need systemic change, and we can’t win systemic change municipality by municipality,” says Garrard. But she warns that even statewide good cause would only be “a bare minimum first step” toward housing justice. A tenant has to actually know about the law and fight it in court if it’s violated, after all.

“That’s the irony of the whole thing. This is such a starting place for even attempting to have some sort of housing equity,” Garrard adds. “New York, which champions itself as a progressive bastion and leader, is actually so far behind on this.”